Shikhar Dhawan is clearly loving life in a Delhi Capitals shirt. Ben Jones takes a close look at how the illustrious Indian left-hander has enhanced his T20 prowess since joining the franchise.

Ahead of the 2019 IPL season, Sunrisers Hyderabad made a choice. They were going to trade their opening batsman, Shikhar Dhawan, to Delhi Capitals. In exchange, they wanted three players: the two all-rounders Vijay Shankar and Abhishek Sharma, plus the finger-spinner Shahbaz Nadeem.

The fact that SRH were asking for three players was an acknowledgement of Dhawan’s stature in the game. This was a marquee Indian player, and while there was a degree of Sunrisers hedging their bets with their incoming personnel, it was also a straightforward question of recognising that value and status. Yet that the fact that the trade was happening at all was an equal acknowledgement, however indirect, that Dhawan was a fading force as a T20 batsman.

From SRH’s point of view, the incoming players have not gone well. Nadeem has taken eight wickets in 11 matches, with a worryingly high economy rate; Shankar has averaged 20 with the bat, and taken only a handful of wickets; Sharma, with the obvious caveat of still being only 20 years old, has failed to force his way into the regular XI.

By contrast, the trade has gone very well – very well indeed – for Delhi Capitals, and Dhawan.

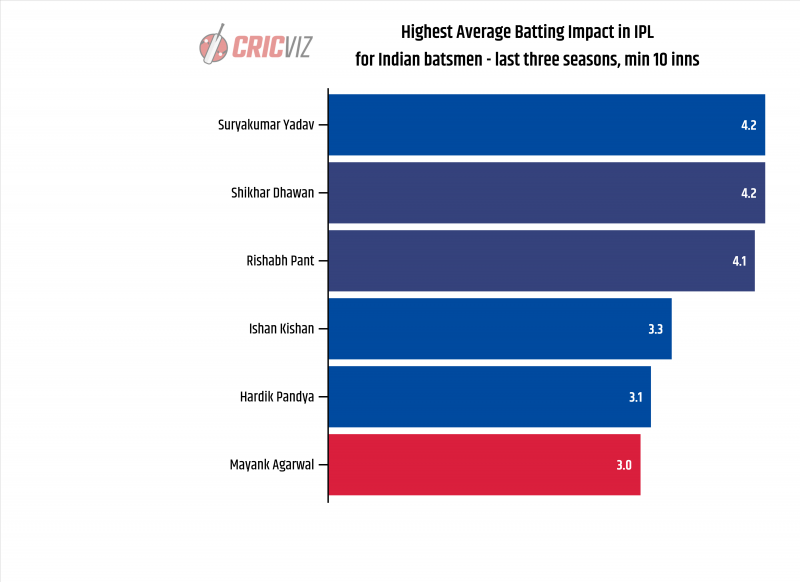

Since joining Delhi at the start of that season, Dhawan has a strong claim to be the best Indian batsman in the tournament – 1370 runs in 37 matches, averaging 42 and scoring at 8.5rpo; 11 half-centuries, and two centuries. In that time, he’s recorded the equal highest Average Batting Impact (ABTI) for an Indian, level with Suryakumar Yadav.

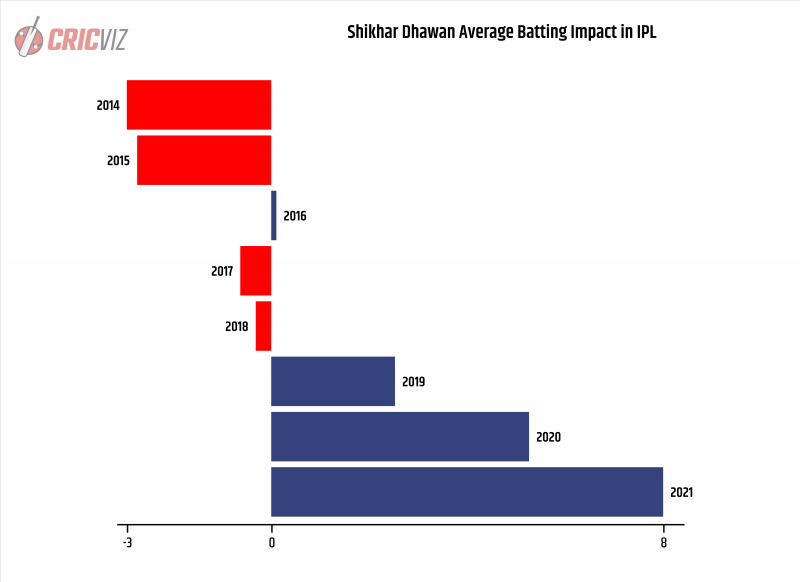

What’s more, that dominance has only increased and intensified with every passing year. Each season since moving to Delhi, Dhawan has improved; his ABTI has increased year on year, and though this season’s impressive +7.6 is likely to fall over the coming weeks, it sits as part of an upward trend. He has kept getting better, and better, and better.

To what can we attribute this huge improvement?

The most commonly cited factor is Dhawan’s “intent”. Partly that’s a consequence of wider discourse in the game, a debate about aggression and control which sucks everything, and everyone, towards it. However, more importantly it’s a response to the notorious press conference early in Ricky Ponting’s tenure at Delhi, when he suggested that his side needed more intent from Dhawan, for him to be more straightforwardly attacking, in order to go to the next level.

Dhawan’s record subsequently improved, Delhi were finalists in the following season, so plenty of onlookers drew Ponting’s declaration and Dhawan’s step up together. But was an increase in intent really the key?

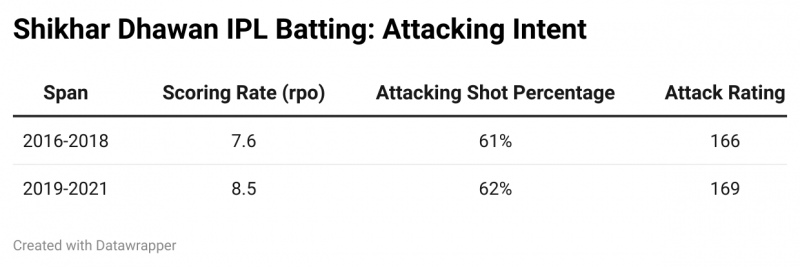

Well, yes – to an extent. There’s no question that Dhawan’s scoring rate has increased, given that flying along at almost 1rpo faster than he had done previously. What is less clear is whether that scoring rate has actually been accompanied by heightened aggression, or attacking intent. Dhawan’s attacking shot percentage has remained essentially stable overall, as has his Attack Rating (a more nuanced measure of intent than attacking shot percentage).

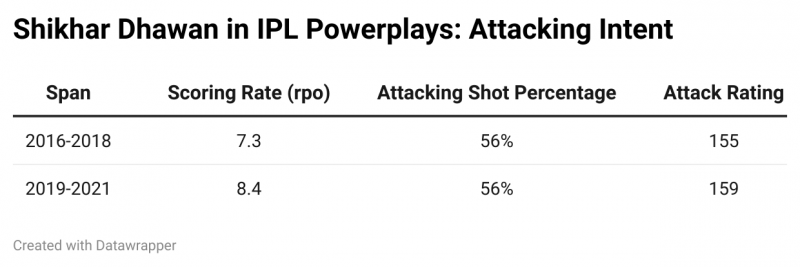

Of course, when we refer to intent, we’re often using it as short-hand for early intent. Everyone’s attacking when they’re set; the difference comes at the outset, both individually and as a team. In the case of Dhawan’s recent record, again we see that at the start of his innings he’s scoring faster than previously, but without a clear increase in overall intent. Ditto for his record in the Powerplay.

So what’s going on?

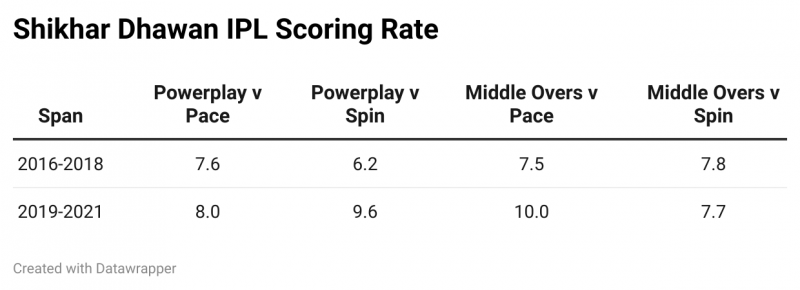

Taking a closer look at the phases where Dhawan’s record has changed most dramatically, reveals a clear pattern. The most obvious driver of this increased scoring rate, is his record against spin in the Powerplay, and pace through the middle.

This is where we do see some increased intent for Dhawan. Against seamers through the middle overs, we see a slim increase in Attack Rating from 186 to 192, but more interestingly, against spinners in the Powerplay, that Attack Rating has risen steeply from 139 to 162. The only obvious area of Dhawan’s game where we have seen a significant increase in attacking intent, is early on against spin.

Dhawan has in essence embraced the idea of getting out early attacking spin, with the trade-off being that he scores so much quicker against it. In 2016-2018, he averaged a whopping 102 when attacking spinners in the Powerplay, but scored at ‘just’ 9rpo. Since moving to Delhi, that average has fallen to 22.85, but the scoring rate has flown up to 13.9rpo. Embracing risk, in exchange for reward – Sunrisers aren’t the only ones who can make trades.

His record through the middle against pace, that increase in scoring rate, is perhaps a consequence of a more offside-focused approach that has come into his game over the last few seasons. Previously, 43% of Dhawan’s runs against pace were scored through the offside; in 2019 and 2020, that rose to 56%. We all know about Dhawan’s cut shot, and what a fundamental element of his game the stroke has always been, but it seems to have become even more prominent. Around a quarter of Dhawan’s runs for Delhi (against pace) have come behind square on the offside, a marked increase on what he was managing for SRH.

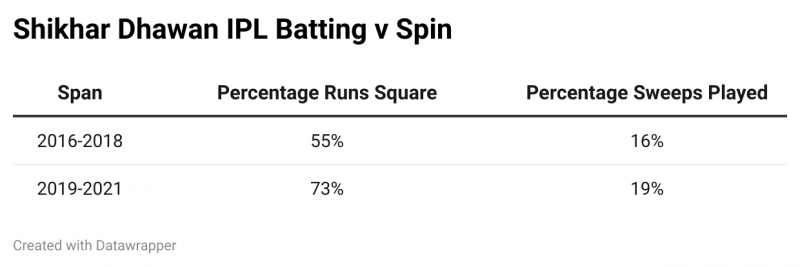

There’s also been an alteration in Dhawan’s scoring patterns against spin. He is scoring much squarer than previously, a greater percentage of his runs coming through the square ‘V’ either side of the ground. Give there’s no discernible increase in his sweep percentage – either conventional, or reverse – it’s fair to attribute this to the ‘paddle-pull’ he’s used so liberally of late, played off the back foot with an almost perfectly horizontal bat, wrists snapping through at the last minute to ensure that the ball goes squarer than you might initially expect. The fact that he pairs this with destructive capability when using his feet to get to the pitch of the ball (80 runs from 40 trips down the track in a Delhi shirt), gives Dhawan a clean, simple, effective method against spin.

Indeed, watching Dhawan at the moment, those are the words which come to mind. As is so often the case for a player in good form, everything looks simple. Those swivels are crisp and smooth, the attacking strokes clipped and well placed to the left or right of fielders. Dhawan looks, at the age of 35 and with an illustrious career behind him, as good as he’s ever done.

The development of Ishan Kishan has given India something they’ve long been denied, a choice of left-handers at the top of the order in their T20 side. For the first time in a long time, if India want a lefty in the opening pair, with all the benefits that brings, they don’t need to pick Dhawan. To be selected, Dhawan has to be more than he’s previously been.

This transformation – and it is nothing less than that – was entirely necessary, to keep Dhawan relevant as a T20 force, particularly in an international context. Now that it’s complete, the temptation for India to select him will be strong. The combination of proven international experience, but boosted by a willingness to attack early in the innings that could more readily be associated with younger, more ‘modern’ players, is a potent one.

For now, the challenge of winning the IPL for Delhi is enough to occupy his attention and focus. For Ponting’s side to leave this mega-auction cycle without a trophy, given the outrageous domestic core that they secured in 2018, would represent a huge missed opportunity, particularly so when the extra year of development for a young squad is factored into the equation. In the absence of captain Shreyas Iyer, Dhawan’s senior status and excellent form is going to be a key cog in their charge for the title.

And that, really, is all the evidence you need to show how this transformation has worked: from a traded player in 2019, a man deemed surplus to requirements, to perhaps the most important player in a side with genuine ambitions to win the whole thing.