It was playboy v firebrand, says Francis Kelly as he recalls the battle for supremacy at the heart of Pakistan’s golden generation – Imran Khan and Javed Miandad made for one of cricket’s most dynamic and volatile relationships.

First published in 2015.

First published in 2015

In the afterglow of the 1992 World Cup win, the fabric of Pakistan cricket, so delicately stitched together, began to unpick. A thrilling victory, marrying the country’s defiance with destructive flair, saw the beginning of the end of a golden generation. The relationship between captain Imran Khan and his right-hand man, Javed Miandad, had rumbled along uneasily across three decades until, in the Australian evening warmth, the pair had combined to craft Pakistan’s greatest feat.

The story of their rise, coming together from different worlds to conquer their adversaries, is the basic plot to countless sagas, but this was an original fairytale for Pakistan cricket. Khan, raised in Lahore in a wealthy family, enjoyed unrivalled schooling at Aitchison College and then Oxford University; Miandad, born four years later, forged his career learning the game on the streets of Karachi with a tape ball.

The contest between the pair stood for more than merely two individuals. It personified the country’s factions since Partition. As the chosen sons of Pakistan’s two grandest cities, they embodied the clash between the nation’s contrasting social classes. At the core, though, was the complex battle between Imran and Javed. Friend and foe. Playboy v firebrand.

[breakout id=”0″][/breakout]

Ever since Pakistan announced themselves on the 1976/77 tour of Australia, drawing the Test series with a first win on Australian soil, the pair changed the national team’s dynamics. As the country’s foremost cricket historian Omar Norman noted: “This was the first time that Miandad and Imran had contributed to a win, but this pattern was to be repeated to telling effect over the next decade and a half.”

***

By that point, Miandad had already become the youngest player to score a Test hundred on debut, reinforcing his prowess by breaking the record for the youngest Test double-centurion in the same series against New Zealand.

Although older than Miandad, Khan’s ascent took a more prolonged route. Travelling to England for schooling aged 18, on the advice of Worcestershire’s chairman Wing Commander William Shakespeare, Imran’s Pakistan career temporarily halted – having played his debut Test in the summer of 1971, he had to wait a further three years before he could add to it. In comparison, Miandad worked his way through the domestic set-up.

From Beefy and Viv to Sarwan and Gayle.https://t.co/ez5EWajlaD

— Wisden (@WisdenCricket) May 24, 2020

While both arrived in the team at almost identical times, Imran at this time – a wild, big-haired tearaway quick – held little of the prestige someone his age might otherwise have demanded. Indeed it wasn’t until Miandad’s three-year captaincy neared its end after large portions of the team rebelled, that divisions began to appear, with Imran emerging as a challenger to Javed’s supremacy.

Javed’s methods, seen as dictatorial, had led to 10 members of the squad going on strike, and although the Pakistan board backed their man, his position in the dressing room was untenable. It was 1981, and a riven team needed a new talisman. Imran’s role in Miandad’s removal as captain is contested, but one thing is for sure – his switch from an impartial standpoint to falling in with the mutineers decided the outcome.

[caption id=”attachment_151346″ align=”alignnone” width=”800″] Miandad masterminded Pakistan’s semi-final chase against New Zealand in the ’92 WC[/caption]

Miandad masterminded Pakistan’s semi-final chase against New Zealand in the ’92 WC[/caption]

With loyalties broken, a replacement proved difficult to agree upon. Revolt leaders Majid Khan – Imran’s cousin – and Zaheer Abbas were passed over for the job, and Imran emerged as a compromise choice. Miandad even backed his selection in an attempt to help unite a fragmented side. Appointed ahead of the 1982 England tour, commentators questioned Imran’s resolve for responsibility, his youthful exuberance known to inhibit his decision-making at times. Yet he shone, averaging 42 with the bat and taking 21 wickets at 19. Miandad fared slightly worse, hitting 178 runs in the three-Test series.

By the end of the year, Imran had demonstrated his ability to lead a group of men, whitewashing Australia at home and then leading India 2-1 going into the fourth Test. Two down for 60, Miandad joined Mudassar Nazar to build a 451-run partnership. Unbeaten on 280 at the close on the second day, Miandad had Garry Sobers’ then Test record score of 365 in sight. Solo achievements mattered to him. Effort was there to be rewarded. The next morning Imran declared, with Miandad unaware of the decision in advance. His moment of personal glory was gone.

***

The rift never disappeared, and while Miandad came to accept Imran as an authoritative captain, even aiding him with field placements and tactics, their personal relationship deteriorated further. Pakistan cricket thrives on needle however, and combined they realised they were an overwhelming force. Series wins over India and England were achieved, and two World Cup semi-finals came and went, the second, in front of a packed Lahore crowd in 1987, the most crushing to take.

There would be no repeat in 1992. Unprecedented excitement greeted the World Cup’s fifth version, the first to be held in Australia, and advertised as the greatest yet. Pakistan arrived early in Australia, but when the original squad was announced, Miandad’s name was missing. Although both Imran and Miandad had appeared in all the preceding tournaments, the captain had chosen to leave his long-term team-mate at home.

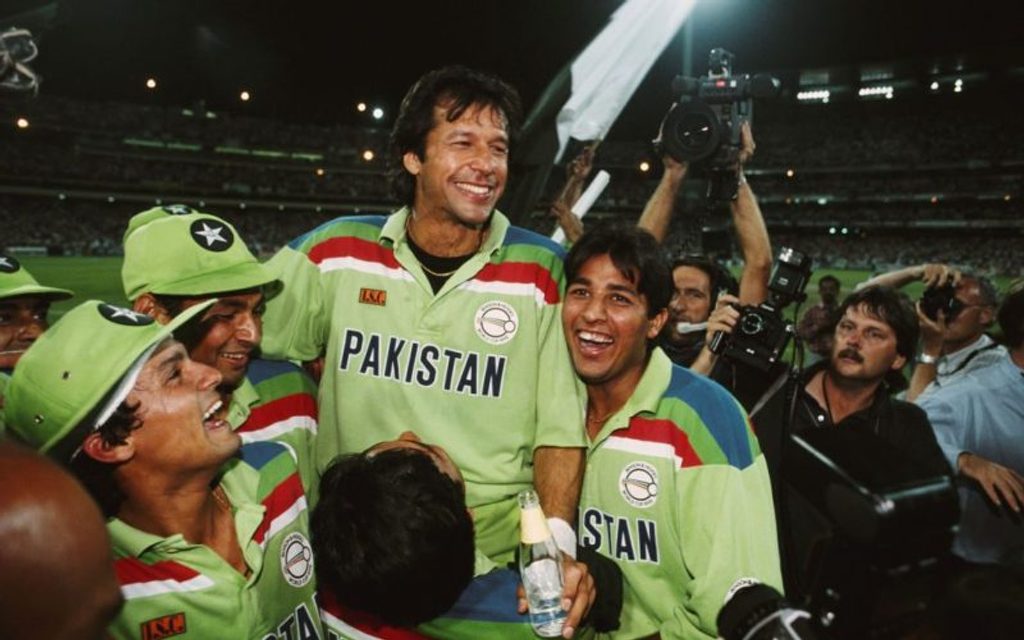

[caption id=”attachment_151347″ align=”alignnone” width=”800″] Imran Khan is hoisted by team-mates after he led Pakistan to the World Cup title[/caption]

Imran Khan is hoisted by team-mates after he led Pakistan to the World Cup title[/caption]

But Javed’s replacements struggled, and after a debilitating series of warm-up game losses, the authorities – acting without Imran’s consent – brought Miandad in from the cold. Miandad later explained the exclusion in his autobiography Cutting Edge: “I couldn’t help feeling it was an attempt to somehow bring me down a notch, to try and diminish whatever stature I had managed to earn as the Pakistan No.4.”

The rest is history. A fumbling start, with Imran injured and Javed out of form, resulting in Pakistan winning just one of their first four games, were all forgotten at Perth, where they defeated the hosts. From then on the momentum was with them, Imran and Miandad making 72 and 58 respectively in the final to put the score beyond England.

[breakout id=”1″][/breakout]

Imran retired straight after the World Cup, but his influence could still be felt, Miandad complaining that he contributed towards him losing the captaincy again in 1992. He offered a barbed explanation that summed up their strained relationship: “Perhaps he felt an undisturbed Miandad captaincy would overshadow his legacy.”