When he wasn’t dominating international attacks for West Indies, Everton Weekes found a home away from home in east Lancashire. Scott Oliver tells the tale of Weekes’ exploits at Bacup CC in the Lancashire League.

Lead image: Bacup CC

So great is the lineage, it need only be designated by first names: Shivnarine and Brian; Curtly and Courtney; Malcolm, Desmond and Joel; Viv, of course, and Gordon, Michael and Andy; Clive, then Wes and Lance and Conrad, and on through Rohan, Garfield and Sonny. And before getting to the pre-War stars, Learie and George, you have the three debutants of 1948 and batting titans of the 1950s, the “three W’s” after whom a cricket ground in Barbados is named: Sir Clyde, Sir Frank and the now-departed Sir Everton. Throw in Richie Richardson and Charlie Griffith, and that’s 14 cricketing knights from those sun-bleached Caribbean shores.

Before his passing on Wednesday at the age of 95, Everton de Courcy Weekes had been the third oldest surviving male Test cricketer. His 10-year career in West Indies colours brought him the monumental figures of 4,455 runs at 58.61 – better than Walcott (3,798 at 56.7) and Worrell (3,860 at 49.5) – as well as the staggering achievement of hundreds in five consecutive Test innings (all of them inside his first 10 knocks), which remains a record to this day, over 70 years later. He went on to become an ICC referee, briefly, as well as a broadcaster and a coach, and was universally regarded as a warm, modest and convivial man with a gentle sense of humour and an appetite for tipple-enhanced card games. And boy could he play. Cricket, that is.

Back in those English summers of the post-War period, long before the county game opened up to overseas players in 1968, Test cricketers would habitually gravitate to the leagues of northern England – usually on much better money than they ever received for international outings – mesmerising the mill towns with their exotic brilliance and lifting local spirits after six years of brutal conflict. The Lancashire League, in particular, was a honeypot for these superstars, coming to host such bona fide greats as Vivian Richards and Shane Warne; Holding, Headley, Hall and Roberts; Dennis Lillee, Steve Waugh and Allan Border; Allan Donald, Kapil Dev and Mohammad Azharuddin, and many more besides.

None of them left so great a mark, though, nor racked up such extraordinary statistics, as Everton Weekes did in his seven seasons at Bacup, a once prosperous cotton town bundled into the Rossendale Valley and overlooked by the forbidding east Lancashire moorlands. Across those seven long-ago summers at the Lanehead ground, a short but steep walk from Bacup town centre, the Bajan maestro crunched, crashed and caressed 9,069 league runs at 91.60 (the highest average in the history of the league), including a record 32 hundreds (only six men have even half that number). Not the worst, then, although his signing was something of a happy accident, as The Authorised History of Bacup CC explains:

“In the winter of 1948/49 West Indies travelled to India for a Test series and spent a night in London en route. Bacup vice-chairman James Hargreaves went to London with the authority to sign Wilf Ferguson, a leg-spinner. Apparently, he declined, but pointed to a young man in the hotel foyer who might be interested. His name was Everton Weekes. The conversation must be preserved for posterity. Hargreaves said, ‘Would you like to come and play for Bacup?’ Weekes replied, ‘Yes I would, provided you think I’m good enough’. The rest is history, glorious history for the town, the club, and the league”.

No doubt the expectant Bacup committee will have been buoyed by news crackling through on the wires that Weekes’ Test scores on that India tour were 128, 194, 162, 101, 90, 56, 48, although they may have been slightly concerned at the alarming drop-off toward the end…

His contract for that 1949 summer was worth £500 (a shade under £18,000 in today’s money), which was no doubt still cheap given the enormous numbers he helped draw through the gate at a ‘bob’ apiece (twenty ‘bobs’, or shillings, in an old pound). Indeed, restored cine-reel from his debut season shows extensive footage of the derby match with neighbours Rawtenstall, which attracted a crowd of around 10,000 to watch Weekes go head to head with Indian star Vijay Hazare.

Hazare would top the league’s bowling and batting averages that year, while completing the double of 1,000 runs and 100 wickets, a feat that had never before been achieved (Australian Cec Pepper, proing at Burnley, matched Hazare that same summer, and only two have managed it since: Colin Miller, for Rawtenstall, and Chris Harris, for Ramsbottom). Nevertheless, Weekes out-performed Hazare on the day, making 74 to the Indian’s solitary single; after the traditional collection box had been taken round that sizeable and impeccably attired crowd, Weekes’ innings – something of a cameo by his standards – had earned him a colossal £48 (more than £1,700 in today’s money).

Weekes also finished the season as the league’s leading run-scorer – with 1,470 at 70, comfortably his lowest season average for Bacup – as he would in all bar his final summer in Lancashire. And in amongst all that was a top score of 195 not out at Enfield – the skipper declaring mid-over with a double-hundred beckoning – which would remain a Lancashire League record for 53 years, until a certain Michael Clarke made 200 not out on the same ground for Ramsbottom in 2002. First impressions? Pretty steady, you would have thought. Or, translated into Lancastrian: He’ll do for us.

The following summer Weekes toured England with West Indies, amassing 2,310 first-class runs at 79.65 – the first five of his seven hundreds on the trip were 232, 304*, 279, 246* and 200* – but Bacup found an able enough deputy in George Headley, ‘the Black Bradman’.

Back for the 1951 season, Weekes collected 1,518 league runs (at 89.3), which remained a record aggregate for 40 years, as did the seven league hundreds he made that summer. And it might have been even more had his own club not banned him for a game, explains club chairman, Neal Wilkinson:

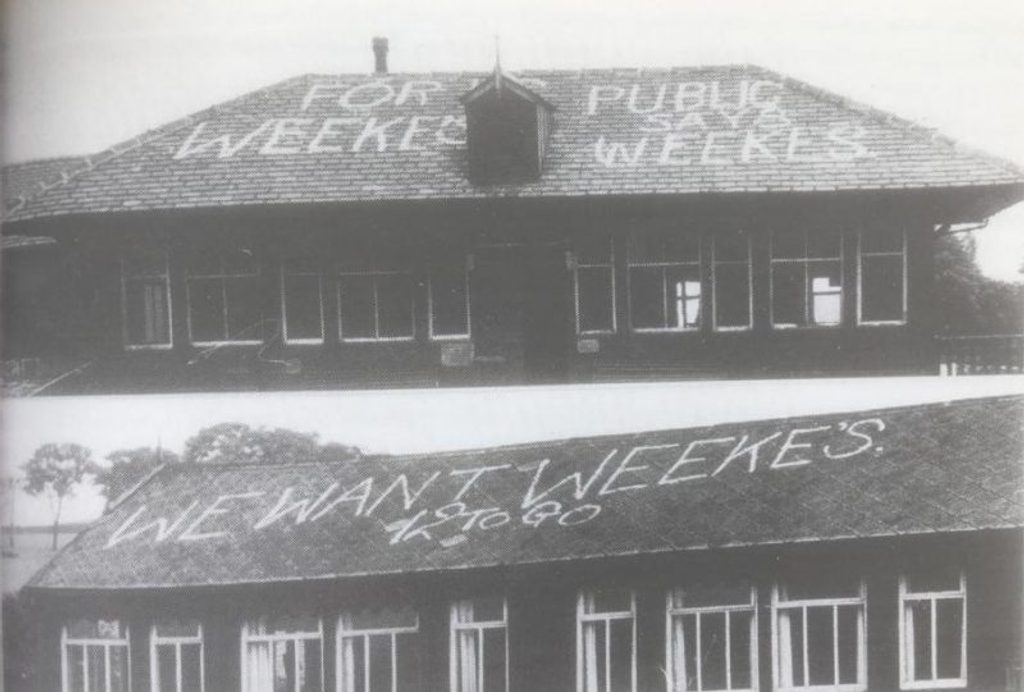

“In those days, the Lancashire League committee were rather above their station. On one occasion, they asked the FA if they would change the Cup Final date because it clashed with Lancashire League fixtures! As a result, a lot of the club committees were of a similar ilk. If players wanted to play elsewhere whilst under contract – even those as good as Everton Weekes – they had to ask the club’s permission. On one occasion, Everton turned out in a representative match, a Commonwealth XI versus England XI at Kingston upon Thames, without asking. Bacup had taken a stand with the league forum on this, and so suspended him. It didn’t go down well with the supporters, some of whom daubed protest slogans in paint on the roof of the pavilion and tea hut, and even on the outfield, calling for Weekes to be reinstated and for the 12 members of the committee to be sacked. The official club history says, ‘Everton responded with great dignity. He could easily have taken his bat home and found another club. He didn’t, and matters were settled in a happy reconciliation, with the suspension lifted after just one week’.”

[caption id=”attachment_163716″ align=”alignnone” width=”800″] Bacup CC fans were not happy with Weekes’ suspension – copyright Bacup CC [/caption]

Bacup CC fans were not happy with Weekes’ suspension – copyright Bacup CC [/caption]

All of which goes to show the sheer degree of celebrity Weekes enjoyed in the area, as well as the depth of affection for the man in a town with which he has become indelibly intertwined. So fully did he embed himself in the community that he even opened a sports shop in the town centre (locals of a certain age have been sharing stories on Facebook of buying their first tennis racket or football boots from Everton Weekes), while he used his regular and sizeable collection swag to help lubricate his teammates’ weekend evenings. “Mind you, back then the club didn’t have its own bar. They made their money on the gate and with teas. So they would all go into town, to the Market Hotel and the British Queen. He liked to get about town, did Everton.”

Not that a Weekes collection hat was a formality, although with 51 half-centuries to add to 32 tons from 150 Lancashire League knocks, he only failed to secure the bonus in 44.66 per cent of his innings (and even then there was the bowling to make up for the shortfall). Very occasionally, he failed to trouble the scorers at all, which hit everyone in the pocket…

“People would turn up in their droves to watch the great Everton Weekes bat,” says Wilkinson, “not just from Bacup but from miles around. The ground is at the top of a hill – it’s pretty much the highest ground in the country – and on one particular occasion Rishton’s professional, Fred Freer, had the audacity to get Everton out first ball of the game, lbw. What’s more, the umpire had the audacity to give him out, and that was a very brave man, believe you me. Legend has it that the crowds of people swarming up the hill heard from the people at the top, ‘He’s out! He’s out!’ And with the news cascading downbank and through the crowd, they all turned around and went home again, costing the club who knows how much money on the gate!”

Despite seemingly powering the local economy almost single-handedly, Weekes lived in modest accommodation: a terraced house on Gordon Street, a stone’s throw from the ground, where he was looked after by his landlady, Maggie Sharrold. “He had to suffer our rather cold summers, compared to what he was used to,” says Wilkinson, “and he had this dark grey Army & Navy Stores overcoat which he wore everywhere he went”.

That summer of 1951, Clyde Walcott was pro for rivals Enfield – Weekes’ compatriot, the man with whom he shared a Test debut, was the only other man to prevent him from topping the batting averages, each winning it twice in Walcott’s four years in the league – while Frank Worrell was the paid man just down the road at Radcliffe of the Central Lancashire League. The “three W’s” would often rendezvous at ‘Flat’ Jack Simmons’ aunt Bertha’s fish and chip shop in Clayton-le-Moors, near Accrington. “They were both regular visitors at Gordon Street, too,” says Wilkinson, “where they’d have jazz-singing and piano-playing sessions after having got stuck into Mrs Sharrold’s famed ‘tater pie suppers, which were diced potatoes, onions, and, if you were lucky, some bits of meat under a crust”.

The Lancashire League supporters already had a strong affinity with their teams on account of a strictly enforced rule which stipulated that all players had to live or work within four miles of their club (the Committee were known to take a ruler to ordnance survey maps in an attempt to resolve disputes), but the bond with the Bajan was something else entirely – something pure and uncontrived, approaching adoration, all buttressed by Weekes’ humility and, says Wilkinson, his total absence of aloofness and self-importance.

“He regularly used to play cricket in the street with the local kids. On one occasion, one of the boys hit the ball through somebody’s front window, at which point all the kids scarpered and poor old Everton was left stood there alone with the irate neighbor, having to explain what happened. Had it been anyone else I think they’d have been even more irate, but he was something of a local deity and even now in the town, you mention his name and people’s eyes light up. His name has been passed down through the stories”.

Indeed, Weekes was so popular during his decade at Lanehead, adds Wilkinson, that it wasn’t uncommon for crowds of hundreds to attend Bacup practice nights, just to see the great man up close: “One evening at practice Everton was batting and, as ever, there was a big crowd round the nets. Somebody ran up to bowl and, just before he delivered, he dropped his bat, pulled out the middle stump and creamed this ball through covers. For a moment there was total stunned silence and then the whole ground burst into a long applause”.

His eye always seemingly in, the scores kept on coming: 1952 saw 1,292 league runs at 80.75, while 1953 brought 1,322 more at 94.42. The following year it was 1,266 runs in 17 innings at the eye-watering average of 158.25, which unsurprisingly remains the highest in the history of the league.

And all this was on far from pristine surfaces against some fine bowlers – at one end at least, with eight-ball overs and no restrictions in place – including three wrist-spinning stalwarts of Australian domestic cricket in George Tribe, Bruce Dooland (both of whom took 1,000 first-class wickets) and Pepper, Indian mystery spinner ‘Fergie’ Gupte, Pakistani pace-bowling godfather Fazal Mahmood, and the great Australian quick Ray Lindwall.

Lindwall failed to dismiss Weekes in the five-Test series in the Caribbean that caused the Barbadian to miss Bacup’s 1955 campaign – Weekes averaged 58.62, almost precisely his career average, and picked up his sole Test wicket. As a “self-taught” bowler, he took 453 league wickets for Bacup at 15.2, with a best of 8-20 and 36 five-wicket hauls (do that for 30 runs or fewer and it meant another collection hat). By the time he was back in Lancashire for the 1956 campaign, however, there was still the club’s lingering itch of not having lifted a trophy since 1930, when they won a league and Worsley Cup double.

“To win the league in those days you had to be able to bowl a side out,” explains Wilkinson. “It was timed cricket and declarations, and what the opposition used to do against Bacup was bat as long as they could, or declare ridiculously late, because they knew how good Everton was. They would have to be seen to be playing the game, but tried not to give him time to knock the runs off. They were frightened to death of him. There are plenty of games when the opposition batted for ages and ages for a relatively middling score, 150 say, and they’d be knocked off in an hour and a bit with Everton 110 not out”.

Weekes contributed 80 league wickets in 1956, while scoring 1,168 runs at 97.33, yet Bacup were pipped by a single point to the title by Burnley. To everyone’s relief and delight, they did win the Worsley Cup, however.

[caption id=”attachment_163717″ align=”alignnone” width=”800″] The 1956 Worsley Cup-winning side – copyright Bacup CC[/caption]

The 1956 Worsley Cup-winning side – copyright Bacup CC[/caption]

This being Lancashire – where the idiosyncratic rules and playing conditions often belie some hard-nosed economic rationality – the finals back then were timeless single-innings matches played over as many consecutive weekday evenings as were necessary to get the game finished, although each innings was suspended at 130, with the other team then invited to bat, before the ‘first’ innings would resume. No one seems to know why. At any rate, Bacup’s perma-performing pro took 6-61 from 32 overs as Nelson were bowled out for 168, in two stints. In reply, Weekes entered at 8-2 and scored an unbeaten 119. It was all done in two nights’ work. The scorecard doesn’t reveal whether there was a Player of the Match award.

Yet perhaps the most extraordinary performance of all those he etched across the pitches of Lancashire came a couple of years earlier, and for another club. With the Bacup committee long having learned their lesson, Weekes was drafted in as sub-pro for neighbouring village Walsden of the Central Lancashire League for their Wood Cup final against Middleton. Save for the innings suspension coming at 150 rather than 130, it followed the same quirky ‘timeless weekday’ format of the Worsley Cup, and so a game that was due to have started at Rochdale CC on August 4 was instead completed on September 1 at Werneth after many rain-truncated evenings during which, says Walsden president Allan Stuttard, “Everton learned how to play three-card brag, which he told me was why he went on to become bridge champion of Barbados”.

Middleton scored 220 all out from 88.3 overs either side of their enforced hiatus, Weekes’ figures a remarkable 43.5-10-92-9. However, when it came to Walsden’s first turn to bat, Weekes was stranded in Ireland after a golfing engagement, and so he didn’t see his team subside to 45 for 5 on their first night’s batting. Rain prevented any further damage, and thankfully the Bajan was on the right side of the Irish Sea by the following evening, coming in at number eight with the innings in deep trouble at 46 for 6. He shepherded them to the 150 suspension without further damage, and then, after finishing off Middleton’s innings, picked up the thread of a 148-run partnership with Jim Wilkinson of which Weekes made 135. He ended unbeaten and triumphant on 151 (out of 178 while he was at the crease), duly securing himself a place in a second club’s hearts.

Having helped Bacup to the itch-scratching Worsley Cup in 1956, Weekes missed the following Lancashire League season due to his second and final West Indies tour to England – by far the most barren series of his career, with 195 runs at 19.5 – and returned in 1958 for a last Lancashire League campaign with his focus firmly set on winning the title. In the meantime, however, he elevated his final Worsley Cup average to 95.41 by carrying his bat for 225 out of 354 against neighbours Rawtenstall in a game spread over six evenings – Monday to Monday, either side of the weekend’s fixtures – which they won by 52.

The title race was again duked out with Burnley, whose pro was Weekes’ West Indies teammate, the hard-hitting off-spinning all-rounder Collie Smith. The teams faced off in the third-last game and, amid the showers, Weekes played an uncharacteristically restrained innings of 56 not out to secure a draw that kept their rivals at arm’s length and which, after victories in their final two outings, ultimately proved enough for the greatest Bacup professional of them all to sign off with that long-coveted Lancashire League trophy in his hands. It was a fine way to bow out, although it was hasta luego rather than adiós.

“He last came to the club in 2014, just short of his 90th birthday,” recalls Wilkinson. “It was a lovely evening. There was a junior match being played, four or five of his old teammates who were still alive attended, and we took the old photo from 1949 off the wall and he re-signed it”.

As he looked out at kids almost 80 years his junior starting their own cricketing stories on what was once his patch, his stage, his manor, no doubt the sounds (and perhaps the more elegant shapes) will have set those fuzzy old memories flickering once again across the old man’s thoughts, memories that transport a man, however fleetingly, to that time when they would be forever young: memories of runs, runs and more runs, runs for the cause, and then carousing around town with those teammates who would still be friends almost 70 years later, before heading back up the hill to his two-up, two-down on Gordon Street for Mrs Sharrold’s leftover ‘tater pie.

Eighty-one times the great man strode out to bat at his home away from home in east Lancashire, far from the familiar crystalline waters and swaying palm trees of Barbados, and only 44 times was he dismissed there. Eighty-one innings in which the grateful Bacupians were treated to the small matter of 5,619 elegant runs at a piffling average of 127.7, with 25 hundreds and 26 fifties.

Just in case you missed that: Everton de Courcy Weekes’ home batting average, rounded up, across seven seasons for Bacup was one hundred and twenty-eight. No wonder Bradman thought him the greatest West Indies batsman he ever laid eyes on. And there was quite a lineage.