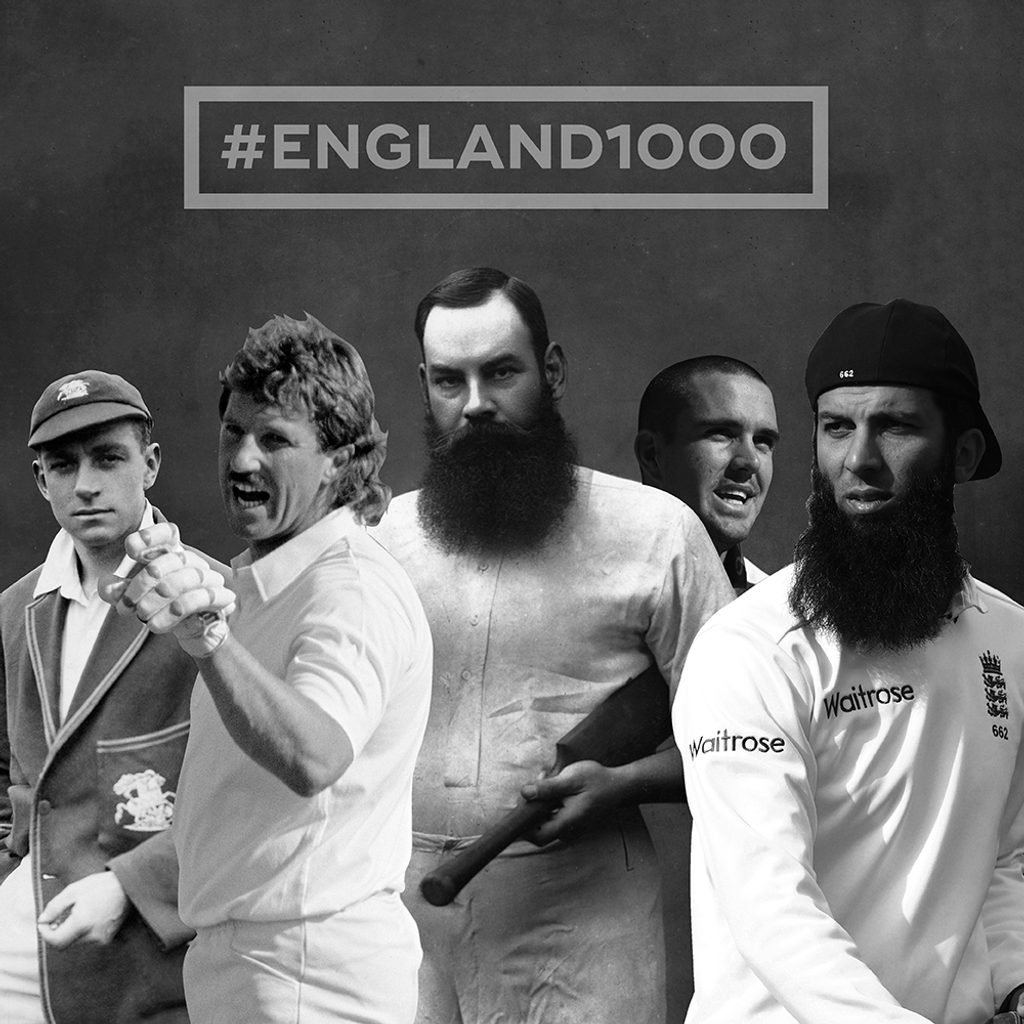

To commemorate the thousandth England Test match – against India at Edgbaston – Wisden Cricket Monthly editor-in-chief Phil Walker picks his XI of players who, for better or worse, encapsulated the spirit of their age.

- WG Grace (22 Tests, 1880-1899; Captain)

- Jack Hobbs (61 Tests, 1908-1930)

- Wally Hammond (85 Tests, 1927-1947)

- Fred Trueman (67 Tests, 1952-1965)

- Tony Greig (58 Tests, 1972-1977)

- Ian Botham (102 Tests, 1977-1992)

- Michael Atherton (115 Tests, 1989-2001)

- Darren Gough (54 Tests, 1994-2003)

- Graeme Swann (60 Tests, 2008-2013)

- Kevin Pietersen (104 Tests, 2005-2014)

- Moeen Ali (50 Tests, 2014-)

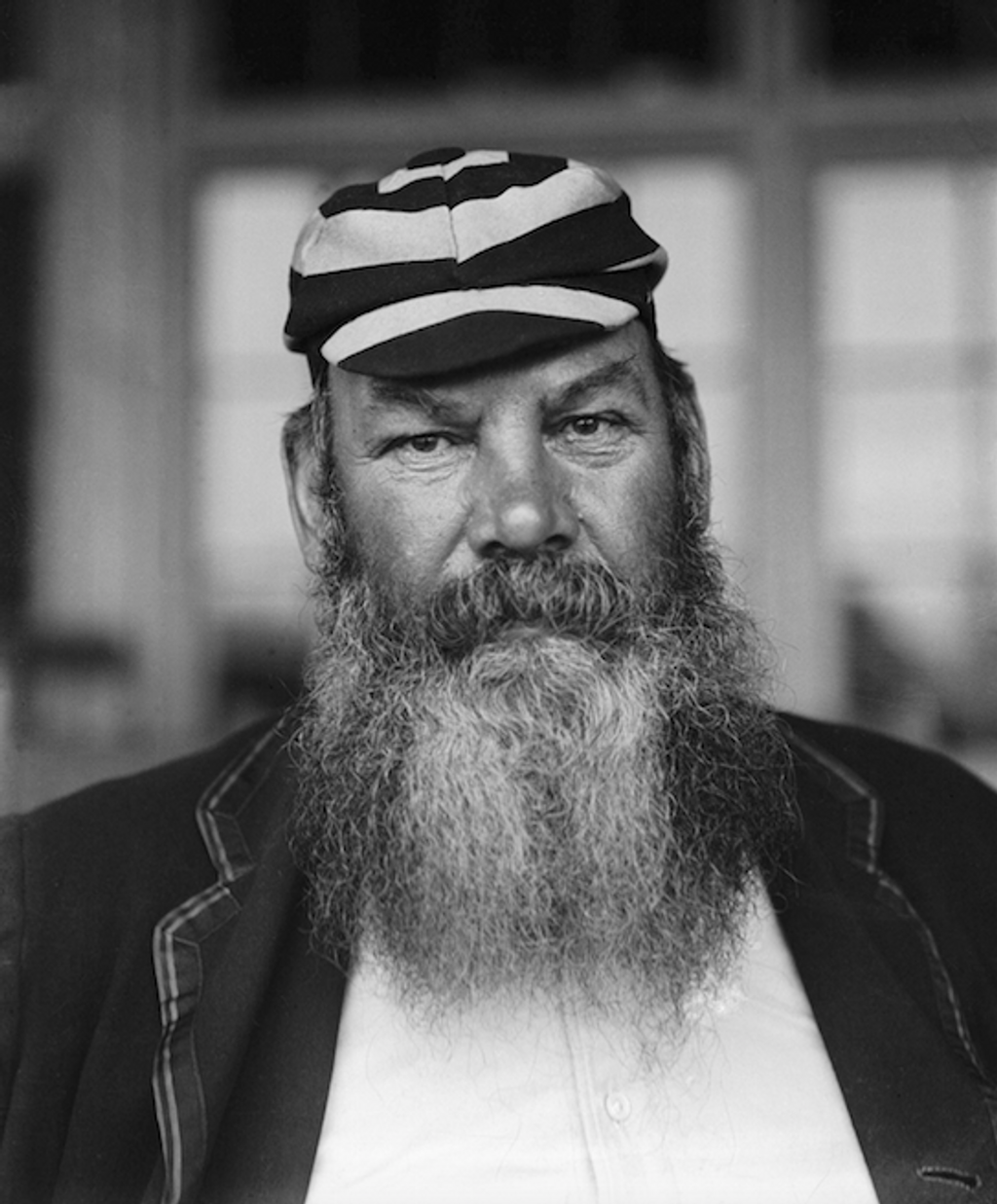

Only one man could lead this bunch. Although five England skippers will traipse out behind him, this is WG‘s team. It all flows from him.

Grace opened in England’s first home Test in 1880 and in front of 21,000 at The Oval made 152. Since then, no other England cricketer has so successfully combined the qualities of genius, longevity, totemic presence, nationhood archetype, commercial behemoth and gargantuan ego into a singular career, although in this dressing room many have tried. He dominated his era to such an extent that, as Geoffrey Moorhouse wrote in Wisden in 1988, Grace was “the best-known Englishman apart from Gladstone” in the country.

[breakout type=”related-story” offset=”0″][/breakout]

How good? He made 10 centuries in a season (1871) when the rest managed seven between them, later became the first man to do the double (1874), hit two triple centuries in a week (1876), make 1,000 runs before May and break the hundred-hundreds barrier (1895). In his pomp, cricket became him. The rest have merely sought to ape him.

He won’t be getting much hassle out of Jack, that’s for sure. Now there’s a man who knows his own worth; after all, Hobbs got paid by the run. Back then, as the historian Gideon Haigh writes, “there was cricket for pleasure and cricket for profit; amateur and professional, oil and water”. Then came Jack. As modest as WG was bellicose yet as insatiable as Grace in his pomp, Hobbs was neither a trailblazer nor a revolutionary, and went about his chosen business of extracting runs with the quiet dignity, not to mention modest pay and long shifts, of an industrial pitman.

But his dedication did much to change attitudes towards ‘professionals’ and subvert Lord Hawke’s infamous refrain, “Pray God that no professional will ever captain England”. John Berry Hobbs was no subscriber to the “rampant Bolshevism” that Harris saw in every nook and cranny. He was, Sir, a runscorer, and he picked up his coin at the end of the day. He played for Surrey till he was well into his fifties, a working man to the last, 199 hundreds, the original Master.

One suspects that Wally (above), on the other hand, would take a little managing; although that said, there remains a good chance that WG would see something in all that barrelling pugnacity and be moved to stick his fellow man of Gloucester in the slips, bowl him second change, bat him first drop (obviously) and even cede the dancefloor after play. If there was a “sense of solitariness” (D.Frith) about the greatest batsman of his time bar one, then so be it; and while absorbing such a singular man into the team ethic would bring its own challenges, it’s fair to say that in that respect, looking down this list, Wally Hammond would not be alone.

Whether Fiery would cede any ground to Hammond or any other toffee-nosed batsman is moot. This dressing room would belong to Frederick Sewards Trueman, and, at a push, his spiritual son, Goughie. And with good reason: the Fifties, the era of Hutton’s professionalism, and the Brylcreem boys of May, Compton et al, was England’s best ever decade in Test cricket, and Trueman was the driving force, bustling and barging his way up the cliff-edge, finally wedging his alpenstock in the 300-wicket mark in 1964, the first to reach that summit. And how did he feel? “Bloody tired”. This was sweaty, matted, unvarnished post-war cricket for a deeply relieved and thankful people, and with his retirement in 1965 came a void that would take some time to fill.

As the Seventies rolled around, Trueman was in a cardigan presenting pub games on Yorkshire TV and commentating on TMS. How England could have done with him; how Tony Greig could have done with him. Australian violence was on its way, and the West Indians were mobilising on the lawn. Spooked, English cricket turned to a South African with a disdain for the fogey old ways of the world he’d infiltrated. “At 6ft 7in, blond and full of vitality, he was an outstanding figure in the 1970s,” writes Scyld Berry of the man who took England to Australia in 1974/75 to face the fury of Lillie and Thomson. England were pulverised but Greig survived to face the Windies in 1976, grovelling through a long, hot summer yet, through sheer chutzpah, retaining the goodwill and loyalty of his team-mates.

By then, cricket was becoming a serious enterprise. Money was sloshing around, serious money, and it was Greig, in 1977, who first made a break for it, sensationally quitting the captaincy for Australia to help set up World Series Cricket, the breakaway that changed professional cricket forever. Those in the Establishment who cried betrayal were presumably blind to the irony that it was Greig’s loyalty to the players, whose sweat and brilliance it was that generated the money in the first place, that drove him out and into the embrace of Australia, where he remained thereafter.

Emerging from Greig’s shadow to dominate the Eighties was, of course, Guy the Gorilla. Botham had himself said of Greig, admiringly, that he “revolutionised the game”; but the charge could just as easily be flipped. Botham, the breakout star woven into the fabric of English life, with the gargantuan appetites to suit that decade of excess, bestrode and probably transcended the game in the early part of that decade. After 1981, he became something other than a cricketer. Not since Compton had a figure crossed the floor so emphatically, but much as English cricket rode on the back of his immense personality and reaped its hefty rewards, so it would buckle a little under its accumulated mass when the salad days turned puff pastry.

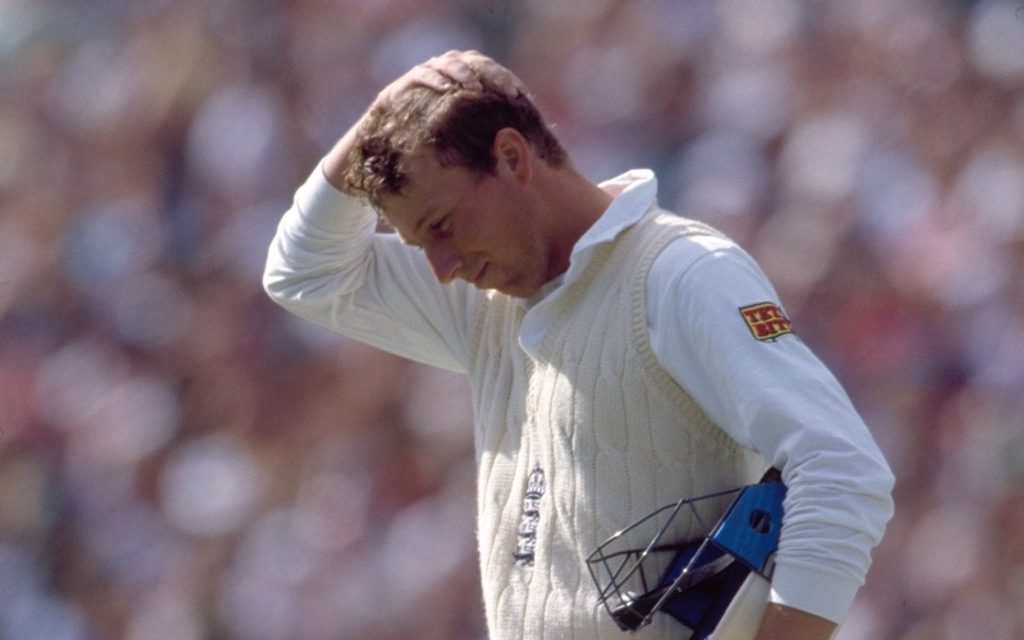

Botham’s final Ashes series was a miserable affair. Gower was captain, and England were expected to win. “If you’d asked me before the ’89 Ashes what could possibly go wrong,” Gower told WCM in July, “I’d have shrugged it off. At the end of it, the answer would have been everything. It had politics, mismanagement, deceit, underhand behaviour – everything.” The good times had stopped rolling. By the time the teams arrived at Old Trafford for the fourth Test Australia were already 2-0 up, and England were about to field another changed line-up, taking the number of players in the series to 21. Unbeknownst to Gower, nine of the 21 had already signed up to a ‘Rebel’ tour of South Africa later that year.

That number would swell to 29 by the end of the sixth and final Test, and Michael Atherton, fresh out of Cambridge, would be one of them. He began with a duck, and followed it in the second innings with an accomplished, cussed 47 as England lost by an innings and plenty. The die was cast.

A little over a year later, at Sydney, he would make the slowest Ashes hundred in history. That would be his one and only hundred against them, from 33 Tests and 15 as captain. Oh, and six wins. Six wins from 33. It was Atherton’s fate to be the frontman. But if success against Australia eluded him, he was at least afforded some succour late in life when in 2000 England finally beat the West Indies for the first time since 1969. And aptly it was Atherton’s one-time attack dog, Darren Gough, who was the driving force, swinging it late into the toes throughout a series that would bring him 25 wickets and, at the last, the one hefty gong of an often brilliant but injury-blighted career. It was the year 2000. Gough would have his yorkers that summer, and Atherton his almost parodically painstaking sign-off hundred at The Oval.

[breakout]Six wins from 33. It was Atherton’s fate to be the frontman[/breakout]

The Nineties were done with, and as the new century took guard, a new confidence began to creep in. Central contracts transformed the landscape. Two divisions sharpened the breeding ground. Players began to identify as internationals first. Duncan Fletcher, a foreigner, landed a job. And when Australia turned up in 2005, and it became evident they were actually in a fight, the whole country stopped what it was doing to pay attention.

Many an alternative XI could have been selected for WG. Was Alec Stewart, he of the upturned collar and record number of defeats, any less the personification of the Nineties than his alter ego? Were Peter May or Denis Compton not just as much the Fifties as Fiery Fred? Was Herbert Sutcliffe not Jack Hobbs in disguise, and does Len Hutton really not get into this team? So far, 686 men have played Test cricket for England. (It could be 687 by the time you read this.) And of the 86 who have debuted in this century alone – this century of Strauss and Cook, Anderson and Broad, Flintoff and Stokes – completing this XI is two spinners and a South African.

Kevin Pietersen and Graeme Swann were not bosom buddies. But they each helped drive England to become, for a shortish but sweet time, the No.1 team in the world. Pietersen did it through freakish one-man feats of hand-eye and ego. He did it by taking on Australia at their own game, and by thriving on the catcalls that rained down on him from the bleachers in Africa, Australia and elsewhere. He did it by proving points, time and again – and often to his own dressing room. He did it his own way, and his own way saw him fall in the end, but not before he’d left an indelible mark on the soul of English cricket.

Swann, meanwhile, was different: by ripping his off-break further than any English spinner in living memory, he reinstated finger spin back into a culture that’s never been too sure of its value. He opened up the back end of Test matches that would otherwise have stayed closed. And as the cocky finisher in a team that knew how to deal with him and each other, he won three Ashes series. As long as Grace keeps them apart, and enlists Wally to step in where necessary, they should be fine.

Finally, to the here and now. At some stage this summer, though not at his home match at Birmingham, where, intriguingly, his pal Adil Rashid has been preferred, Moeen Ali will begin his second fifty. He will wander out (somewhere in the middle order), take guard, and, if it’s his day, unfurl some shots that will linger well into next week. Then when called upon to bowl, he will drag a few down, and float a few full.

[breakout type=”related-story” offset=”1″][/breakout]

And he will take wickets, as he always does in England, to win games of cricket for his team. And a few days afterwards, at a sponsors event somewhere in urban England, as the latest push to grab the hearts and minds strains to play itself out, he will sit down in his training top, and articulate with absolute conviction the importance of being a role model for a new kind of Britain. And all the while, he will smile wryly and pull at the tips of his beard; the most famous beard in English cricket since, well, the most famous beard in English cricket.