The Adrian Shankar Files, part five, by Scott Oliver. Part four is available to read here.

In The Adrian Shankar Files, a seven-part series, Scott Oliver delves deep into new material about a player who, in May 2011, was fired just 16 days after signing for Worcestershire when it was discovered that his age and the tournaments he claimed to have played in had been fabricated. We will see in detail how Shankar attempted to land an IPL contract with the help of radical bat brand Mongoose, who saw him as the perfect marketing vehicle in their attempts to crack the Indian market, as well as the methods used to secure his Worcestershire deal.

Part five covers Shankar’s stay in Sri Lanka, the attempts to get him a gig as a replacement player at Kings XI Punjab, and a piece by ‘Prof. Ron Goldbeck’, on Shankar seeing off Lashings’ Shoaib Akhtar before cracking Shahid Afridi all around Fenner’s.

***

By late February 2011, despite the efforts of Marcus Codrington Fernandez, Zubin Bharucha, Johan Conn, Johan van Niekerk, Morne Erasmus, Manoj Ramachandran and Vikram Singh – despite Alan Norburt! – Adrian Shankar stock still had no IPL buyers. Despite the efforts of Peter Hunter, he still had no takers in county cricket. The IPL auction was now over six weeks in the rear-view mirror and the attention of the wider cricketing world had shifted to the World Cup. Not long before India and England played out an epic tie in Bangalore – a game in which Sachin caressed 120, handsome number 11 ‘Gooser James Anderson went round the park (9.5-0-91-0), the promising young white-ball batter Virat Kohli (recently likened by Conn to an unheralded and equally marketable English player) came in at number 7, Andrew Strauss won Player of the Match for his 158 (opening with his mate Kevin Pietersen) and Ajmal Shahzad biffed his first ball for six in the final over – Shankar headed to Sri Lanka, ostensibly for some practice in spinning conditions should he be called up as an injury replacement by a franchise.

The trip was arranged through Ravi de Silva, agent of another Mongoose player, Chamara Kapugedera. You may recall that ‘Ravi de Silva’ was the name subsequently given to the tournament director of the fictitious Mercantile T20 competition cited by Worcestershire a couple of months later as the prime reason for signing Shankar. Spelling out ‘Our Vision’ on the hastily built website that had emerged while Worcestershire investigated Shankar’s backstory – approximately 8 hours and 15 minutes of graft for ‘John Winton’ as the encroaching flames lapped at Shankar’s house of cards – the fictional ‘Ravi de Silva’ said:

[breakout id=”0″][/breakout]

This was the just the sort of tournament in which an unknown might prosper, and Worcestershire had also mentioned when announcing the signing that Shankar had “made three consecutive hundreds in the longer form of the game”. The real Ravi de Silva believes that, despite hooking him up with Colombo CC (in the top tier of Sri Lanka’s first-class structure), Shankar did not play any matches at all during his stay on the island, only nets, and certainly no top-flight cricket.

It was within those lonely, humid, cricket-less weeks in Sri Lanka that Shankar would start to apportion more of his attention to the coming county season – not all of it, not yet – to which end the Mercantile T20 would eventually be born (after all, the Impalas tournament and the Notts innings were fast becoming yesterday’s fake news). But before that, a week or so after arriving, still with no IPL takers, isolated and uncertain about what the future held, he needed reassurance that his chief ally, Codrington Fernandez, was still onside. So, he asked him – via a character called ‘Umesh Pandani’.

[breakout id=”1″][/breakout]

Effectively, this was asking your mate to ask his girlfriend to ask your girlfriend how she was feeling. Evidently, Shankar felt he could not ask Codrington Fernandez directly, lest he received an answer he did not want to hear, an answer that suffocated the inner fantasy. Nevertheless, as Pandani cleverly intuited, Shankar also couldn’t have all his eggs in the IPL basket, despite the obvious desire for his subcontinental acclimatisation not to be in vain. He had to have half an eye looking ahead to the English summer, to hedge his bets.

With Peter Hunter having made no headway in early November, nor in his follow-up email of March 2 (an abrupt, “Marcus, Did you ever make any progress with Shankar re Somerset? Did you manage to speak to Trescothick about it? He would be great in our T20 side”), another county was needed. One with a ‘Gooser, of course. On March 10, the nominatively determinate ‘Derek Wiseman’ wrote in to Mongoose:

[breakout id=”2″][/breakout]

As vivid as Shankar’s imagination evidently was, these county-fan emails were becoming as formulaic as Ramsay’s Kitchen Nightmares USA. The hidden potential spotted (“I really think he would add some fizz to our line up”). The yearning helplessness (“I don’t know what else someone of my humble stature can do”). The mate-can-you-make-Gooserman-get-the-county-to-sign-him-yeah (“I was thinking particularly of another Mongoose player, Jim Allenby, who is now VC and would be quite influential”). Same, but now grabbing him by the figurative collar and ramming it down his throat (“Perhaps you can talk to him?”). The reminder that people need to gamble (“I think with these T20 guys [yes, really] that come out of nowhere…”). The unwieldy menu, the slapdash cooking, the dated décor, the demotivated staff, the exasperated expletives (“Oh come … fucking … on, yes?”), the long hard look at themselves, the deep clean, the re-setting of standards, the rekindling of passions, the $40k overnight makeover, the tears, the ersatz family therapy, the new start, the thank you Chef Ramsay, the IPL, the Blast, the Impalas pop-up, the Mercantile T20, the thunderous pulls, the blurring hand-speed, the top-order fireworks displays, the infectious swagger, the name up in lights…

Five days after the Wiseman play, a glimmer of light appeared on the horizon. Shankar sent in some IPL news – this time bona fide – detailing that Kings XI Punjab would replace the injured Stuart Broad and Dimi Mascarenhas: “Worth putting in a call to Gilchrist?” (the Australian legend Adam was Kings XI skipper). Codrington Fernandez replied by asking how he was getting on: “What are the conditions like? Playing as well as you had hoped to? Are you keeping a list of all your scores?” There was a tender naiveté to this last question, and the likely answer was that, yes, he could probably knock something together. In reply to the first two questions, though, Shankar sent in a dispatch that was circulated among the Mongoose staff.

[breakout id=”3″][/breakout]

The cricketing summation was atypically cursory, the pivot to business hard. The IPL clock was ticking, after all. The next day, Codrington Fernandez emailed Stephen Lee Atkinson, Adam Gilchrist’s manager.

[breakout id=”4″][/breakout]

Beneath this was typed out a list of Shankar’s scores in “pro T20 games”: the 50 and 83 for Impalas, the T20 warm-up 104 against Notts (with Graeme Swann now listed in the attack), plus, for balance, innings of three against Derbyshire (presumably in the same T20 warm-up) and two against MCC (for whom it wasn’t entirely clear). A small sample-size, then, to demonstrate how the “2010 stats reflect” what Codrington Fernandez calls “the real tale”.

He also attached five of the Shankar-centric features, including Alan Norburt’s report on the “all-star thriller” between Rochdale and Heywood (from CLL to IPL). Atkinson replied: “He certainly looks a prospect.” However, Gilchrist didn’t follow up – assuming he had any input on player recruitment, or even that he was informed – with Kings XI instead opting for Ryan McLaren and David Miller as replacements for Broad and Mascarenhas. Rather than Shankar.

[caption id=”attachment_207773″ align=”alignnone” width=”800″] Adam Gilchrist in action for Kings XI Punjab in 2011[/caption]

Adam Gilchrist in action for Kings XI Punjab in 2011[/caption]

It bears repeating that Codrington Fernandez believed every word of this: the assumption that Gilchrist’s manager will have heard of Shankar, his suitability for Kings XI, the film-star looks and marketability, the impressive scores, that he was playing for Colombo CC (which could have been verified with a call to Ravi de Silva), the potential to “set India alight” – all of it. There is no collusion in Shankar’s deceptions, no awareness that he was a prodigious fantasist. The sheer scale of the gullibility is remarkable, however, as is the way the UTPE nudges seem to have wormed their way into his very thoughts and language. Shankar was thus a name “on many people’s lips at the IPL auction” (Conn), is “hugely marketable” (Ramachandran) and an “inventive” striker of the ball (Erasmus’ remarks on the reverse-ramp shot that “first silenced a baying crowd then sent them into a frenzy”). Beyond this, there is the regurgitation of the more directly absorbed Shankar mythos, about the transformational family tragedy that flicked his ball-striking switch, since when he has played with “unfettered mea culpe [sic] abandon”.

These were far from the only problems here, either, or even the most significant. Was Shankar really – and it is not clear why Gilchrist’s agent would “probably know” this – having “advanced conversation with another franchise for a long term contract, starting in 2012”? Which is to say, did Codrington Fernandez know this was a falsehood, or was he relaying something told him by Shankar? Or was it, perhaps, a misconstrual deriving from Rajasthan – which is to say, Zubin Bharucha – not yet having given a definitive negative? If Shankar were truly in advanced talks for a long-term deal, this would mean he was going to be earmarked as a ‘retained player’ (the 2011 list was Dhoni, Vijay, Raina, Albie Morkel, Sehwag, Tendulkar, Harbhajan, Pollard, Malinga, Warne, Watson and Kohli), since all others go back to auction each year, which Codrington Fernandez ought to have been able to figure out. And if he were to be such a player, why was Codrington Fernandez offering him to Kings XI “before that deal was completed”?

Furthermore, was Codrington Fernandez telling the truth when he wrote, “Zubin … and I wanted to recommend a player to you” and “both Zubin and I have total confidence in him, as we feel he is an unmined gem”? Had Bharucha indicated this to him or was Codrington Fernandez unjustifiably leveraging the name of an influential IPL figure, specifically in scouting, in order to stoke interest?

There are many questions and few answers. Atkinson has not responded to an approach for comment. Codrington Fernandez has declined to offer comment when asked about various aspects of this email. Bharucha and Manoj Badale have also been approached for comment on several aspects of this email – there has been no response from Badale, while Bharucha has said, apropos what might be considered a conflict of interests: “I completely deny being involved in making any joint recommendation to Kings XI or anyone else”. He also said: “There was a tremendous effort made to mask the cricketing credentials of [Shankar]. There clearly was a strategy to feed false information, with an intention of deceiving people. As indicated earlier, I have in fact been a victim of such deceit and it was quite disappointing to have faced such a situation. It was very unpleasant to have experienced a complete breach of trust. It is crystal clear that there has been no arrangement or transaction that has been concluded by me with [Shankar] or [Codrington Fernandez].”

Bharucha has said that his Kadamba analyst’s failure to unearth footage of Shankar on December 29 was “the red flag” that made him “absolutely insist on a trial”. Shankar had not yet had this trial at the time of this email to Atkinson, nor would he ever take up the offer. Then again, Bharucha also told Codrington Fernandez on December 17 that he was “pushing Kochi [Tuskers Kerala] hard to bid for Adrian,” also before a trial and thus without having seen him bat (with the possible exception of several years earlier, when Shankar attended the World Cricket Academy, run by fellow Royals scout Monty Desai and at which Bharucha also worked).

Indeed, a question that may or may not have occurred to Atkinson was this: if Shankar was genuinely the player being depicted by Codrington Fernandez – and Erasmus, Conn, van Niekerk, Ramachandran and Norburt – then you would think Rajasthan, with five overseas slots unused, might have taken a punt on the player at auction, especially at $20k. As Johan Conn so perceptively grasped: “With teams scrapping it out over uncapped domestic players who are bargaining for far more than their base price, a prudent owner would probably look seriously at the young Englishman […] Outside the marquee names, there is probably no other player who would offer a franchise as much value on and off the field in a market like India.”

Whatever the mysteries, the tone of Codrington Fernandez’s email to Atkinson (and earlier to Dermot Reeve) is quintessentially that of the advertising man. He punchily hits all the high notes while creating a vague air of demand, even emphasising his marketability with capital letters. He has been utterly ‘seduced’ by Shankar and the myriad press reports, sucked in by a con artist who expertly (and a little dementedly) created an incredible – or, indeed, for some, credible – buzz around himself.

The whole Shankar MO was redolent of Carlos Kaiser, “the greatest footballer never to have played football,” about whom Rob Smyth wrote in the Guardian:

Kaiser had more front than Copacabana Beach. His staple trick was to make friends with influential people: he would befriend powerful figures at each club, telling them about his impressive football CV. If he was in the mood, he would approach journalists, players and the club owner, constructing a web of lies so elaborate that nobody could remember who had vouched for him in the first place.

In those days, before the internet, nobody was much the wiser. Even if they had the inclination to check – and Rio has never been the most anal of places – they wouldn’t have been able to do so. “Life,” says Kaiser, “is marketing” – and he told his stories with such infectious conviction that it was easy to be swept along. Bebeto, the World Cup-winning striker of 1994, says: “His chat was so good that if you let him open his mouth, that would be it. He’d charm you. You couldn’t avoid it. That would be it.”

In the first training session Kaiser usually suffered a muscle injury that would keep him out for an indefinite period, during which he would hang around the club and become an unofficial morale specialist.

Despite all the pushing, by late March, with the World Cup coming to a close and IPL4 approaching fast, Shankar’s prospects for his dream gig – “if a franchise is brave enough, he may turn out to be a darling of the Indian crowds” (Erasmus) – were fast receding. The air was coming out of his tyres. Isolated in Colombo, with time on his hands and no organised cricket to play, perhaps sat in his Lancashire CCC shorts with the ceiling fan on to worry away the oppressive air, he once more attacked his laptop. He then forwarded on to the Mongoose team a piece that he said had been sent him by ‘Cricket 24/7’, who had added the message: “Remember this? They do a ‘Best I’ve Seen’ series on Cricinfo, cricket365 and other websites. This was submitted recently by one of the old writers at Cambridge.”

[breakout id=”5″][/breakout]

Professor Goldbeck’s wistful reminiscences were arguably the most poignant of Shankar’s journalistic fictions – if only because it was seemingly the least ‘instrumental’ of them, the least aligned on end goals. An academic’s opinion of a one-over assault in what was essentially a beer match against mainly veterans playing at half-cock was unlikely to influence anyone save MCF, certainly no-one at CSK, RCB or KKR. This was pure indulgence, 100% proof pathos. More significantly, it marks a psychological return (or ‘regression’) to the good old days at Cambridge, when the sky was the limit for the Varsity skipper, the world his oyster, before Mother Cricket started to put obstacles to the game’s higher reaches in his way – an experience many go through, and most face with stoicism and dignity.

[caption id=”attachment_207772″ align=”alignnone” width=”547″] Adrian Shankar with Cambridge University CC at Lord’s[/caption]

Adrian Shankar with Cambridge University CC at Lord’s[/caption]

The report was also untrue, and not only because there is no record of a Ron Goldbeck having taught at Cambridge University. Even with the benefit of the doubt on that front, the old don’s recollection must be faulty, for his account of “the one player of genuine quality in recent times” is not corroborated by the archive. It was true that Shankar played against a Lashings team featuring Afridi in 2004, but he scored 22 in 11 overs as the leg-spinner sent down a spell of 6-1-30-1 – impossible maths for the batter, unlikely for the bowler. Also, Shoaib Akhtar didn’t play in the game, although had he done it’s doubtful he would have thundered in, no matter how severely Shankar had dealt with his short ball. Bigger battles ahead. (The following year – a game in which, pace Goldbeck, Sachin Tendulkar did not appear – Shankar made a run-a-ball 56 against a Lashings attack that shared over half the overs between the bowling might of Richie Richardson, VVS Laxman, Jimmy Adams and Rashid Latif. It was unlikely he would find a similar attack in IPL4, should he get there.)

It is unclear to which academic discipline Professor Goldbeck belonged, although were he to have had a similar vocational calling to former Cambridge University and England captain Mike Brearley, who later became a psychoanalyst, he might have been tempted to wonder what lay behind these fabulations, what fuelled them, not least his own august contribution to the oeuvre. Scratching a little deeper, and mindful of the Goldwater rule, Goldbeck and Brearley might have ruminated upon the origins of the (seemingly narcissistic) grandiosity that was implicit in the entire project, the long con, and explicit in the bogus writings’ reference to Shankar’s attributes, especially the non-cricketing ones: “we have not yet touched on his brand value, which is something other players simply don’t offer” due to his “infectious swagger” (Conn); “the lad is a bit of a one-off … unlike any other player I’ve ever seen” (Hunter); “his brand appeal may be unparalleled, with an almost perfectly scripted combination of cover model looks, an Indian father and a Cambridge educated turn of phrase” and who offers “the possibility of the most aesthetic promotional campaign” (Ramachandran); and so forth.

What could be the roots of the psychological traits percolating through these writings? Might it be that Shankar’s journey from Bedford School to Cambridge University marked the smooth upward trajectory of his cricketing prospects, the period in which his achievements broadly matched his self-image (give or take a tussle with Afridi), and everything thereafter was a disappointment that could not be psychically integrated, could not be reconciled with the self-image. The inaugural Wisden essay winner Brian Carpenter recalls meeting the high-achieving Dr Shankar at Lord’s in 2007 during the India Test and him being “more proud of the fact that his son had been to Cambridge than that, as has repeatedly been mentioned over the last few days, he’d played in the same school side as Alastair Cook … He probably knew his son’s main claim to fame in the future would revolve around someone he’d played with.” The angst caused by those sharply divergent paths of players who once seemed of similar ability.

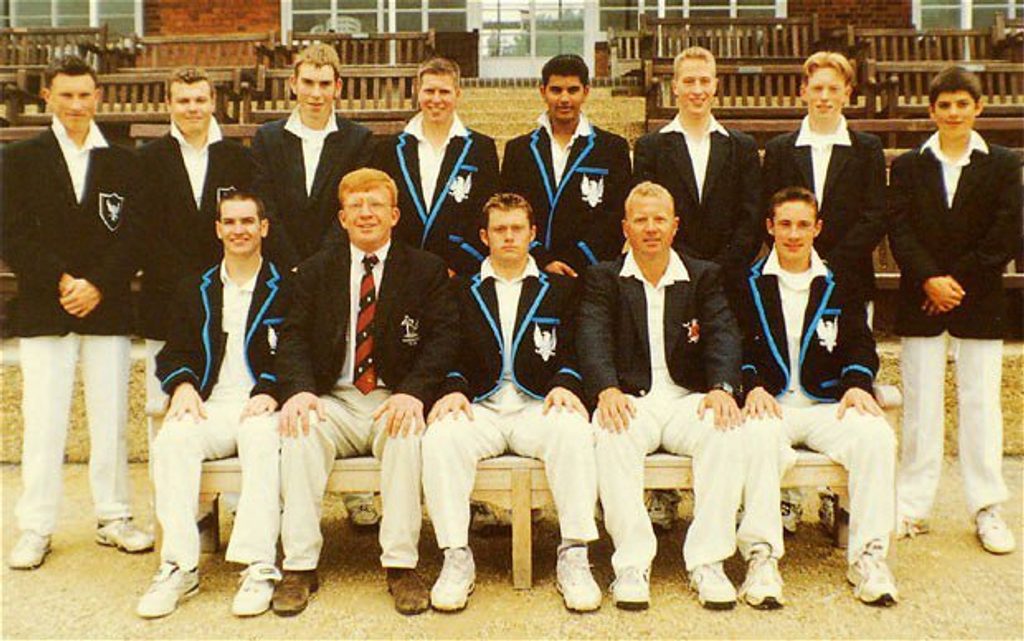

[caption id=”attachment_207769″ align=”alignnone” width=”620″] Bedford School 1st XI, 1999. Shankar, back middle. Cook, back right[/caption]

Bedford School 1st XI, 1999. Shankar, back middle. Cook, back right[/caption]

That first-year Varsity 143 – the innings that Codrington Fernandez argued “irrefutably confirms his quality” – was the apogee, along with the kudos of his two years as captain. If it were the case that, either in reality or in Shankar’s perception (the difference being moot, psychologically), paternal approbation – which can be subtly or overtly conveyed, and to which young people are especially sensitive – somehow depended on his continued achievement, then it is not difficult to see how any underlying insecurity that had first given rise to the grandiosity and the fibs would be aggravated enough to bring on the more baroque and all-consuming falsehoods that followed, a fantasy world made of wax left next to a roaring fire. Investment in the false-self system – displacing the inner struggle over who he really was – would provide a psychic ‘resolution’ to the conflict in which it didn’t particularly matter whether the achievements eliciting the approval and admiration were real or not, so long as the plaudits were forthcoming and so long as there was that (imaginary) persona Shankar could inhabit in order to lap them all up (a novel spin on the self-help mantra of ‘being the best version of yourself’). This would doubtless explain the ‘addiction’ to the admiration of, and approbation from, Codrington Fernandez, here via the solicitations of Umesh Pandani.

Yes, Cambridge was the high point – albeit not a very lofty high point in the eyes of IPL decision-makers, as we shall see – even if, while there, the narrative ointment already contained the fly of his non-selection for two thirds of the first-class games in those final two years (one of which he may not have been eligible for). Thereafter, things went nowhere, through failed trials and club cricket mediocrity, until the still largely inexplicable Lancashire signing in late 2008. But the important thing was to manage the narrative, to account for the time spent off the stellar upward path – first, between University and Lancashire (glandular fever, part-time Masters in International Relations, Kent IIs), then during his Lancashire stint (Conn: “He looked set for a starring role in Lancashire’s T20 campaign after a blazing hundred in a warm up match against a Nottinghamshire side that included Nannes and Sidebottom, but a minor injury and then a shock family tragedy meant that he did not feature”), then around his Lancashire departure (you will recall Norburt’s match report: “It is little wonder that several counties are seeking his signature for next year, and there is little Lancashire can do to stop him leaving as he is on the last year of his contract”; and you will recall Peter Hunter’s email: “I am told that the main reasons for his current situation are personal as much as anything – he could have signed elsewhere in the country but for his family concerns”). The Lancashire departure could only be palatably presented to the world as the result of a family tragedy that simultaneously prompted both a move back south and him batting with “unfettered mea culpe [sic] abandon”. (There never was any mea culpa, not even after Worcestershire.)

Written amidst the shrinking horizons of those oppressive late-March afternoons in Colombo, the Goldbeck variation sent Shankar back – albeit via a fictitious innings – to the happy place of open horizons and cricketing possibilities, to the time when “he [was] talked about as a future star after coming to prominence for Cambridge University” (Conn). The gnawing truth, though, soon to be exposed in his final IPL moonshot, was that there was no prominence to this – it was itself a delusion, perhaps fomented by photographs of Dexter, Brearley, Atherton and Crawley on the Fenner’s walls. The truth – the chafing, irksome, unavoidable truth – was precisely that he wasn’t being spoken about in cricketing circles. And certainly not as a future star – except, perhaps, in his own head, maybe in his own home, certainly in the florid cold-pitch emails of Codrington Fernandez.

Whether Shankar’s next port-of-call would be back-door passes to the IPL glitz or a surprise entry into the more sedate world of county cricket, he needed a new post-Lancs element to the still-on-track “unmined gem” narrative, one confirming his re-invention as a T20 dasher, a format in which the regular failures of a top-order fireworks display are baked in. An off-radar ‘rebel’ inter-city T20 tournament, for instance.

This is the fifth in a seven-part series. Part four is available to read here.