With Rohit Sharma starting the World Cup in fifth gear, CricViz analyst Ben Jones dive deep into the methods behind the India captain’s madness and how India’s batting order has followed suit.

To bet on the World Cup with our Match Centre Partners bet365 head here.

As India have charged to three wins from three matches, there has been little jeopardy, save for a nervous hour against the Australians in Chennai. On that occasion, the dependable middle order of Virat Kohli and KL Rahul dug the hosts out of a hole, carrying them from an all too familiar 2-3 to victory. But it’s been their other two wins where the real party has started.

The party-starter? Look no further than the man at the top of the order, Rohit Sharma. A six-ball duck against Australia was an inauspicious start, but dazzling innings against Afghanistan (131 from 84 balls) and Pakistan (86 from 63) have seen the Indian skipper light up this World Cup.

This devastating series of displays has not come out of nowhere. In the last two years, largely since assuming the captaincy, Rohit has been a batter transformed. The classic trademarks of his game are still there for all to see – the effortless power, the 360 range – but with a new, revitalised level of intent. The Rohit Sharma we are seeing in 2023, in this World Cup, is a man in a rush.

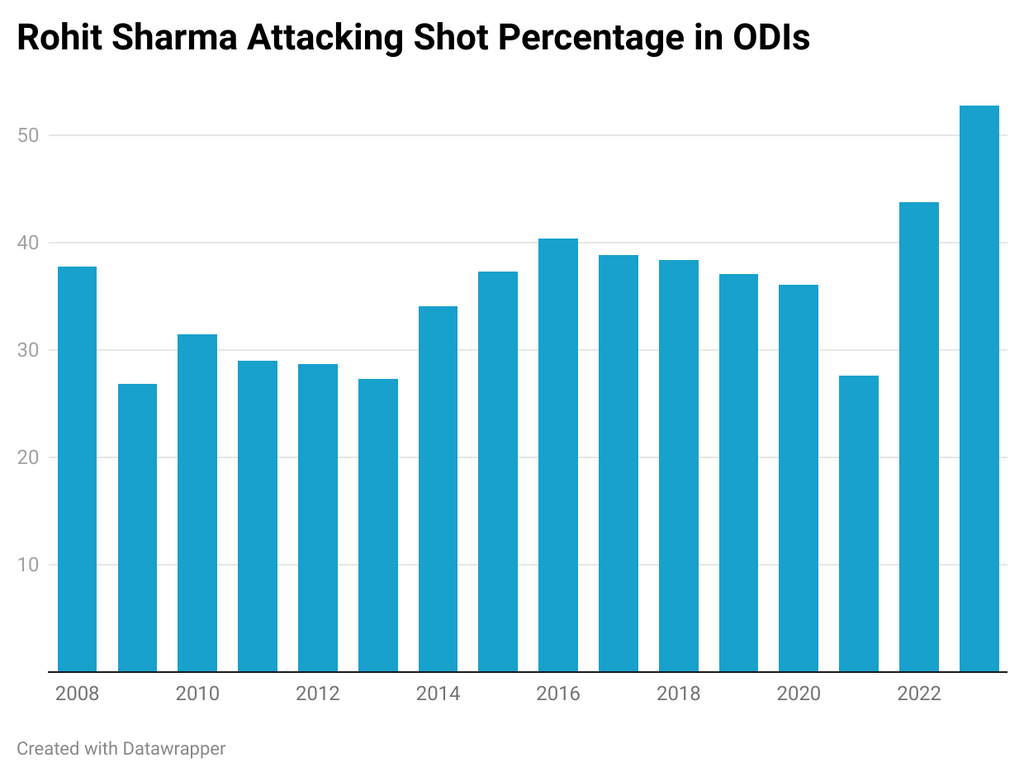

Since the start of last year, Rohit’s attacking shot percentage has soared. Clearly, he has always been an aggressive player and one looking to put bowlers on the back foot, but there has always been a certain rhythm to his innings, a consistent pace. While his individual shots are things of beauty, and his status as a genuinely powerful ‘touch player’ is rare, there has rarely been a sense of reckless energy to a Rohit innings. A cynic could even go as far as saying there’s been a coldness, a level of clinical process.

Right now, there’s an abandon to Rohit’s play. He is going for boundaries more than ever before, testing the limits of his technique and resolve under pressure. He’s already managed a scarcely believable five centuries in a single World Cup campaign; consistency has merit, but this isn’t just about individual records. This is about trying to elevate his side, to take them to a long-evaded title.

[breakout id=”0″][/breakout]

So far in this World Cup, Rohit has battered everything that’s come his way. Against full deliveries he’s swatted them away at a strike rate of 164, while short balls have gone at 159. This is a common pattern for many players though – the real marker is how he’s dealt with good length balls, still striking at a very impressive 121. That’s the indicator of intent. He hasn’t waited for bad balls, he’s made good balls look bad.

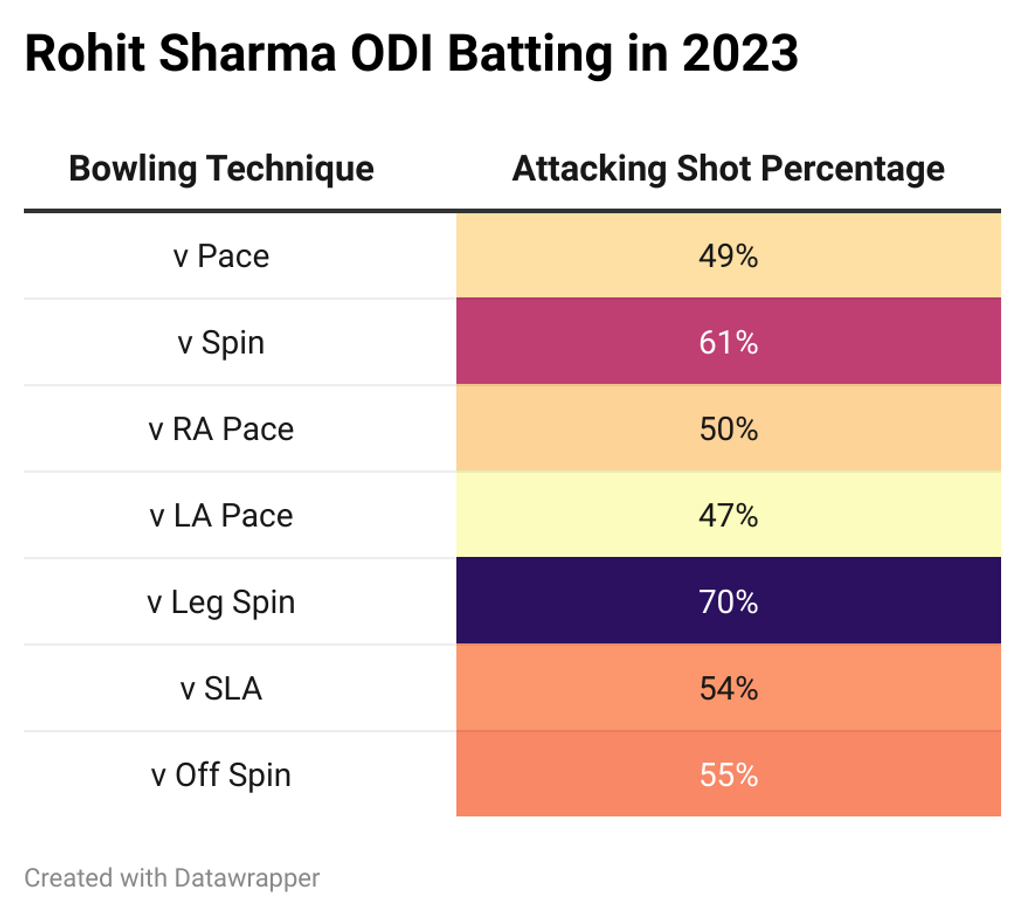

This pattern of taking on all-comers extends beyond this campaign. In 2023, if you’re a seamer bowling to Rohit and he doesn’t try and hit you for four, take a deep breath – because it’s coming next ball. And yet, frankly you’re getting off lightly compared to the spinners, against whom he’s attacking 61% of the time.

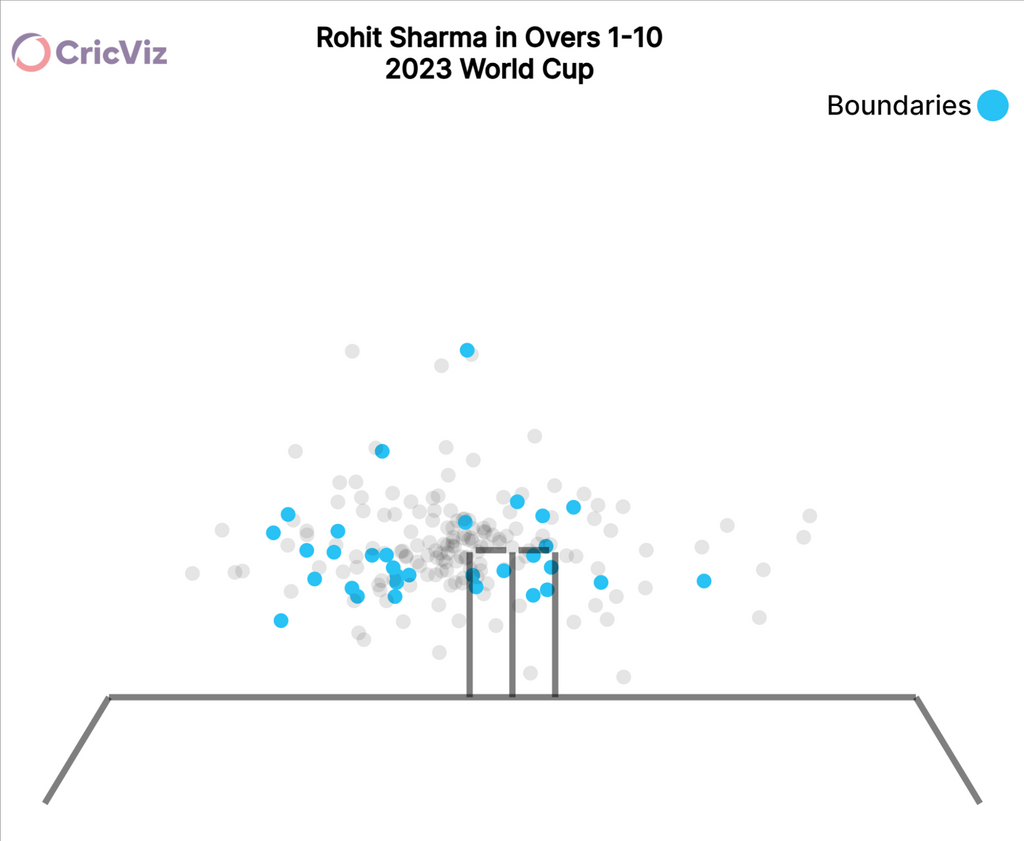

Against Afghanistan and Pakistan, it was the first 10 overs which saw the real force of Rohit’s power, with 76 (40) and 45 (30) respectively. The classic dilemma of whether to maximise the fielding restrictions or to negotiate the early movement is inherent to opening the batting in any format, and for many years India stood firmly with the latter, but Rohit’s recent renaissance has flipped that on its head. More than we have seen in this format, India are attacking that early movement.

Because yes, like all the best leaders, Rohit appears to have brought his team with him into a new stylistic world. KL Rahul and Virat Kohli have also recorded career best intent against spin this year, records which stand up alongside the best we’ve seen since this data has been collated. The knocking-it-about contagion which has struck many an Indian white ball campaign of late has, seemingly, been cured. India have started hitting sixes at a rate they have previously found tricky. In 2023, India have hit just 3.3 fours for every six, their best ratio for a calendar year. Second on that list? 2022.

[breakout id=”1″][/breakout]

While it may seem like a risky approach for India – and for this group of batters – the risk has always been going too far the other way. In moments of high pressure, in knockout cricket, far too often they have retreated into themselves and struggled to assert their skill and class onto (generally) less-fancied opponents. Top order collapses will still happen, as we saw against Australia last week, but the combination of selection (KL Rahul at No.5 is solidity with style when the chance arises) and a greater level of default aggression makes those stumbling, mismanaged bat-first matches far less likely than previous. Since he took over, Rohit’s India have batted first and made between 240 and 280 on just two occasions, from 22 innings.

Dravid-ball, as some rather flippantly termed it, feels like a misnomer. Such is the culture of Indian cricket, so accustomed to cults of personality and enthralled devotion to senior players, that a coach can only ever do so much to change the style and complexion of a team. Change can come from above, but it’s from the captain, from the senior players, rather than from the man in the tracksuit.

The fact that Rohit as captain and Kohli as a senior player have so clearly bought into this way of playing, is far more likely to instil genuine trust and belief in the approach. The speed with which Shubman Gill has come to dominate in this format is testament primarily to his own skill, but also to a slight shift in approach. In a rather different way, the trajectory of Mohammed Siraj from a disastrous 2022 IPL to becoming one of the world’s most attacking new ball operators, speaks to the same thing.

[breakout id=”2″][/breakout]

We have seen this optimism before of course. India’s T20 side showed similarly free-wheeling good-vibes in the early days of Rohit and Dravid’s partnership, only to produce arguably the nadir of poorly paced target-setting, as their top three prodded the ball around Adelaide Oval before England blitzed them in return. A year of build-up and excitement vanished, when these new skills were put under pressure in a knockout game.

Now, Indian supporters once again have cause for that optimism, perhaps even more so than 12 months ago, but you still can’t shake that question of what will happen if they are put back in that situation, in that same cauldron.

This week they have another incremental increase in pressure, their victorious opponents from the Old Trafford semi-final four years ago. New Zealand’s new ball attack of Trent Boult and Matt Henry has been potent so far this campaign, and will test the resolve of India’s new approach. Success will prove plenty – how they respond to potential failure could prove even more.