CricViz analyst Ben Jones takes a close look at Tymal Mills, a T20 bowler who stands out from the crowd.

Cricket has always had an odd relationship with orthodoxy. The MCC manual is a by-word for old-fashioned prescriptive coaching, but its very existence is evidence for the idea of a ‘right way’ of playing the game, and thus a ‘wrong way’. The game has always been conflicted, torn between holding up the orthodox masterpieces of Tendulkar, Sangakkara, while being blessed with innovators (Bradman, Muralitharan, Smith) who have dominated the game to an equal or even greater degree. Technical heresy bringing success is a huge part of cricket’s history.

T20 cricket is no different. Dilscoops, Switch Hits, 60mph leggies and mystery spin – if you stand apart from the crowd with your skills, chances are you’ll do pretty damn well.

Just ask Tymal Mills.

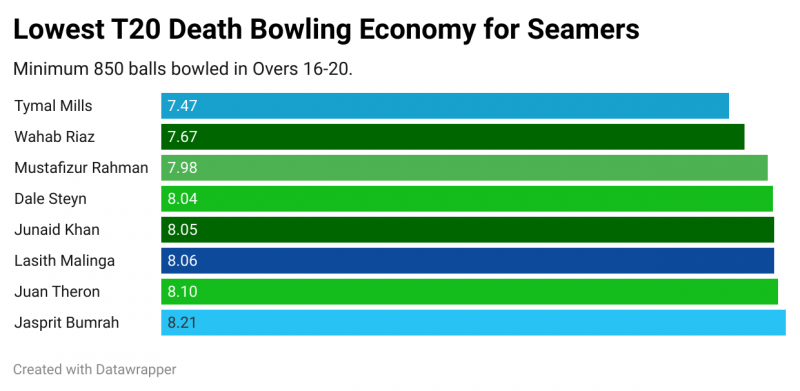

Mills, the English left-arm seamer plying his trade for Sussex, is statistically one of the best death bowlers T20 has ever seen. In the history of the format, there have been 52 seamers to bowl as often at the death as Mills – not one of them has a better economy rate than him. Not Malinga, not Bumrah, not anyone.

Mills is not your average death bowler, in any sense. The most commonly used death bowling method in T20 cricket, and white-ball cricket more generally, is the yorker. Full and straight, hunting the bottom of the bat and the stumps beyond, a well executed yorker is an immensely difficult ball to hit – depending on your definition, those deliveries have an economy of between 6rpo and 6.5rpo. However, a failed yorker – either too full or too short, both more common than their run-preserving colleague – is among the easiest balls to hit in the game with, that economy rate rising to around 10rpo. Going after yorkers is like firing first in a duel. You really can’t miss.

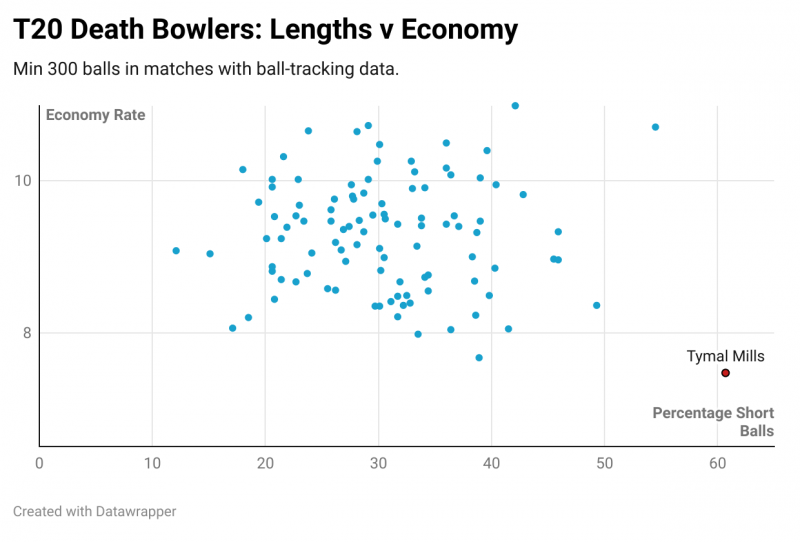

Mills knows this, and acts accordingly. He doesn’t try to bowl yorkers. Instead, he bowls into the pitch, with a variety of pace off and pace on deliveries, landing safely away from that ‘slot’ zone on which most batsmen prey. Nobody has a better death economy than Mills, and nobody bowls more short balls.

The question of why seamers don’t follow the practice of a man with Mills’ record is probably a question for another day. One reason could be seen in the first T20I between England and Pakistan, when Tom Curran’s successful yorker was applauded vociferously, despite near identical balls disappearing to the boundary in the same over. People don’t applaud three mid-pitch slower balls going for three singles; the yorker offers a clear moment of success, and with that, glory.

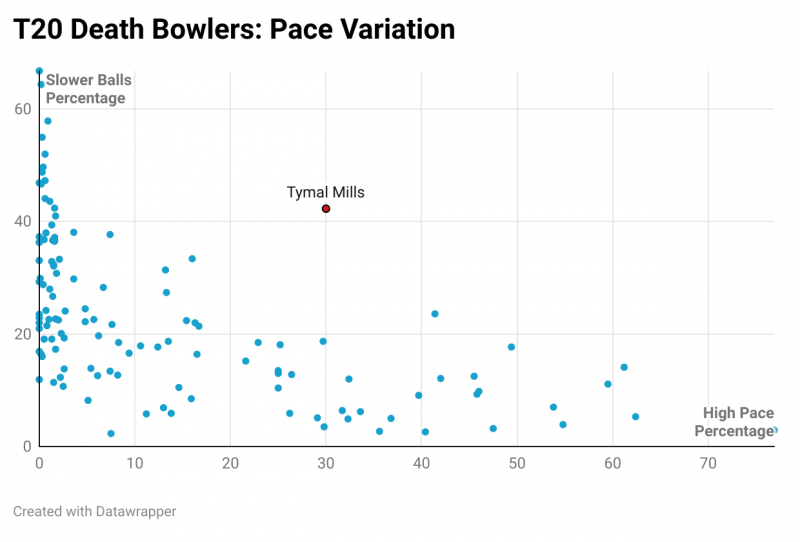

Another less psychological and more technical reason for why players don’t seem to mimic Mills’ approach, is simply that physically they can’t match his speed. There are lots of effective T20 bowlers whose approach is focused on into-the-wicket lengths, and slower ball variations, but what separates Mills from the pack is that on top of those skills, he has genuine pace. Batsmen can’t set themselves for slower variations in quite the same way as with other bowlers, because there’s a 90mph bouncer around the corner to keep you honest. You can see below, that the players who bowl as many slower balls as Mills are guys who simply cannot bowl 90mph. Again, Mills is shown to be a highly original, borderline unique operator.

On the field, this method stands apart from almost everyone else, so it’s only appropriate that off the pitch, Mills is also something of an outlier. Severe, chronic back issues have plagued his career, and forced him into all but retiring from longer formats; he hasn’t played a game of FC or List-A cricket since 2015, choosing to focus his career on T20, and the more physically manageable workload that accompanies it. Without question, that choice (made when he was just 22 years old, and very much seen as a potential Test bowler) has prolonged his playing career, but however successful it’s been it still marks him out as different, an anomaly. A young English batsman who only plays T20 cricket is still not as common as it could be; a young English bowler who only plays T20 cricket is all but unique.

One upshot of that decision is that Mills has had the opportunity to go and test himself in overseas leagues. Some have been qualified successes (brief stints in the BPL, IPL, and PSL) while others (a season at Hobart Hurricanes in the BBL) have been less impressive. Yet for all his statistical brilliance, there is justifiable criticism of Mills’ record for being boosted by his T20 Blast numbers, with his home competition remaining comfortably his best. England have made no secret of their trust in overseas leagues for identifying the cream of their domestic talent, and Mills’ long-time absence from the international set-up may be a consequence of Eoin Morgan et al’s lack of trust (merited or otherwise) in the T20 Blast.

We say ‘et al’, but as with everything in this England T20 side, Morgan is the key. He’s the main reason, even with Mills’ incredible statistical record, that we are talking about him as a genuine option for England at the upcoming World Cup. Unprompted, after his side had cruised to a 3-0 T20I series win over Sri Lanka, Morgan chose to map out a route into the side for those pushing for a World Cup berth – and out of everyone he could have name-checked, he chose Mills.

“If everybody was fit, I don’t think there are many [spots] nailed down – there’s probably half a dozen. There’s a significant period of time [before the World Cup]. We’re dealing with experienced guys within, say, the 17 or 18 that have been involved [and] there are guys playing in the Hundred like Tymal Mills who could easily present a case… He is an outstanding bowler and we’ve always been in communication with him, wanting him to get fit, play as much cricket as possible, and leave him alone until the World Cup comes.”

That last phrase is the most relevant one for Mills. The idea that England have been ‘leaving him alone’, letting him manage his fitness and his own game without the fuss of international call-ups, doesn’t feel too unfamiliar for this England side. The reasons for Jofra Archer’s late-entry into the ODI side, mere weeks before the 2019 World Cup began, were completely different to the reasons keeping Mills out of the XI, but the general logic is parallel. Morgan has seen, in the closest possible quarters, the benefits of adding in a fresh talent into a well-grooved team environment, even at the last possible moment. While Mills is not of Archer’s quality – few in the world are – there is potential for a similar impact given the extreme nature of his approach. This isn’t simply a man with a good record in the Blast banging the door down, but rather one doing something fundamentally different in order to achieve his excellent results.

Southern Brave, Mills’ team in The Hundred, are the strongest side on paper by quite a margin. The nature of the tournament’s structure – shorter, an ostensibly higher playing standard, more visible – allows for compelling cases for international selection to be made in broad daylight. There will be increased scrutiny, varied playing conditions but with the expectation of consistent quality. This is a platform for Mills to showcase his unorthodox excellence, a higher platform than he’s ever had in this country, and a timely one. The message could not be clearer: dominate The Hundred, help define a new competition, and there’s a seat on the plane with your name on it.