As a fresh-faced England side prepared to take on New Zealand and South Africa in the summer of 1994, newfound cricket fan Emma John was brimming with misguided optimism. Even her hero’s disgrace couldn’t shake her belief in a brighter future.

Published in 2016

Published in 2016

I spent a lot of time reading dystopian novels in my early teenage years. My friends and I may have been too early for The Hunger Games, but we shared well-thumbed copies of 1984 and The Handmaid’s Tale, and endless stories set in the aftermath of nuclear holocaust. These kind of terrifyingly bleak reads were, in many ways, a good grounding for the apocalyptic world of England cricket of the 1990s – an age when bad things happened to good people, and every child’s dream was crushed by the totalitarian horror of a savage and ruthless Australian machine.

But it wasn’t always like that.

There was hope, once; the promise of a different future. In 1994 – before the invincible empire of Steve Waugh began to rise, and his enforcer, Darth Warne, held our throats in his death grip – Mike Atherton’s team were about to play New Zealand on their own (damp, seaming) turf. New players were being blooded under a young captain and there was still the potential for any one of them – Craig White, perhaps, or Steve Rhodes – to emerge as a Jedi.

England had lost to the West Indies in the winter of 1993/94, but they’d shown some guts against the formidable attack of Courtney Walsh and Curtly Ambrose. Now they faced a Test side that had, in their 65-year Test history, won just four series. The series was a kind of teething ring; something to chew on, to develop some bite, before England sat down at the grown-up’s table with South Africa later in the summer.

It was also something of a training toy for me: the first home series I’d approached as a fully-fledged fan. I’d fallen for the game midway through the Ashes series the previous year, and spent the winter swotting up, learning everything I could about cricket from books, from newspapers, and from my mother. I was still woefully naive, of course. I believed in the England team as I had never believed in anything before – not Christmas, not my Brownie Guide promise, not even my dad’s ability to fix anything I broke.

But this was a heady time. As a teenager, I demonstrated the classic adolescent duality of enervating hopelessness and aggressive self-righteousness. (No doubt this was why I enjoyed the dystopian fiction so much.) The world was – without doubt – a terrible and futile place, being destroyed by venal, self-important old men. Only clear-sighted, pure-hearted youth could save it from its doomed trajectory. Atherton’s new England were part of that campaign.

The Kiwi team were also favouring youth over experience. In Shane Thomson, Stephen Fleming and the 22-year-old Dion Nash they even had a few players whose pictures wouldn’t disgrace a schoolgirl’s locker wall. (Not mine, I hasten to add. I was far too loyal for that.) The series was a demonstration of potential rather than proficiency, and when England won the ODI series and the first Test – by an innings – it confirmed my conviction that I had joined this sport at the dawning of a new era.

[breakout id=”0″][/breakout]

It didn’t dampen my celebrations in the least that the ODI victory had consisted of a single game (the other was rained off), or that England only saved the second Test by the skin of Steve Rhodes’ bat, when the wicketkeeper blocked out the final session with a dwindling tail for company. They couldn’t finish the Kiwi batsmen off in the third Test at Old Trafford either. But how was a novice like me to know that a 1-0 victory over Ken Rutherford and a largely crocked Mark Greatbatch was not something you should get excited about?

I learned fast, that summer. When Kepler Wessels’ South Africa arrived, their rainbow flag resplendent on the visitor’s balcony at Lord’s, I realised for the first time that cricket was about far more than what happened on the field of play. And if the celebration of South Africa’s return from sporting purdah engendered high emotion – well, so did the discovery that Atherton had been walking around with pockets full of dirt, which he’d been nonchalantly applying to the ball.

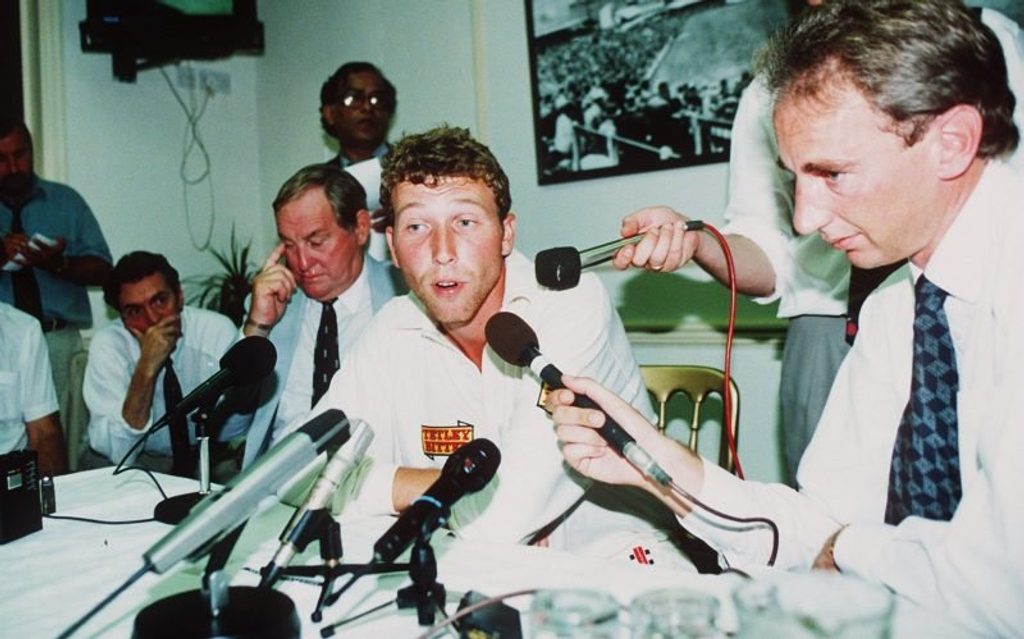

My chief impression of the furore that followed – the fines, the press conferences, one newspaper’s demand to “show us your trousers” – was that being England cricket captain is a more highly scrutinised position than the Archbishop of Canterbury. And that anyone squeamish at the sight of a man being hounded to resign his job won’t last long as a sports fan. If I’d been baptised into the faith of England cricket in 1993, then Pocketgate was my confirmation, my coming of age, and the moment I realised that martyrdom was an inbuilt part of the cause.

[caption id=”attachment_182690″ align=”alignnone” width=”800″] Atherton faces questions over ball-tampering allegations during the first Test against South Africa at Lord’s[/caption]

Atherton faces questions over ball-tampering allegations during the first Test against South Africa at Lord’s[/caption]

Still, looking back at a distance of 20 years, it’s not the hard lessons that prevail. Whatever worldliness I acquired that summer, it’s the scent of hopefulness that still wafts down the decades. The way Darren Gough bounded into my consciousness for the first time, against New Zealand at Old Trafford, England 235-7, a stocky 23-year-old with gelled hair and limpid blue eyes strutting to the crease, and blasting a half-century with an abandon I had not yet seen in an England batsman, much less a No.9. The way his skiddy bowling hurried and hustled the granite-faced South Africans. The way his joyous grin reflected in the fielders’ faces around him.

If there was a pinnacle to that summer’s optimism, it was Devon Malcolm’s bowling at the Oval, a climactic end to a tumultuous season. I remember a few of the deliveries – the one that sent Jonty Rhodes to hospital, for instance. But I also remember the contributions others made, be it Joey Benjamin’s four wickets in the first innings, or Rhodes leaping, salmon-like, to take a catch off Craig Matthews. Most of all I remember Phillip DeFreitas running full pelt to snaffle a boundary catch on his knees, then jumping up straight to applaud the bowler. It was an image of a team invested in each other.

We thought, then, that Malcolm’s devastating nine-for was a teaser trailer for more blockbusting feats to come. In fact, it was the peak of his powers, a perfect and cosmically rare alignment of pace and accuracy. It stood throughout the decade that followed as an embodiment of promise unfulfilled – just one more flash of St Elmo’s Fire, dazzling us with its electric light, signifying nothing. But oh, how beautiful it was.