In the home summer of 2022, England used a seemingly outrageous strategy to take on formidable bowling attacks. The answer to its long-term sustainability lies in the future, but Bazball – christened after the nickname of their new coach, Brendon McCullum – has intrigued the cricket fraternity. Wisden India head of content Abhishek Mukherjee gives a neutral’s view on England’s approach this summer.

Something had to give, somewhere. The bowlers – the faster ones, to be very specific – had been running away with the laurels otherwise. They were coming at the batters, not in pairs but in packs of threes and even fours, providing them with no breathing space.

It may not be an exaggeration to call the past five years the Golden Age of Fast Bowling. We often assign that moniker to the 1970s to the 1990s – and we can hardly be blamed for that. The West Indies attack of the era was not merely fast, hostile, and devastating: they also stood out because almost never in history has a side left out specialist spinners for so long.

The rise of fast bowling in that era was facilitated by Kerry Packer’s SuperTests, a three-way contest featuring some of the best in business. Whatever hesitation they had in using the bouncer generously reduced with the advent of the helmet. And reverse swing ensured the fast bowlers remained just as relevant as the ball got older.

Yet, batters continued to dominate. While every reason behind that is beyond the scope of this piece, one is of vital importance here. Wasim Akram and Waqar Younis, Curtly Ambrose and Courtney Walsh, Allan Donald and Shaun Pollock were incredible pairs. They were also, individually, all-time great fast bowlers. But unlike spinners, pacers – even two of them at the same time – needed breaks.

There were sometimes three at the same time (Ian Bishop’s injuries denied him a long career), but four was rare. Some sides – Australia, India, Sri Lanka – boasted outstanding spinners, but they did not have a second fast bowler who would help form a pair. Pakistan had two excellent spinners (as did India, after a while, as well), but could play only one of them outside Asia.

Most batters, thus, knew which bowlers to play out, and whom to take on. The bowlers were still effective, but not as much as they would have been had they been part of quartets.

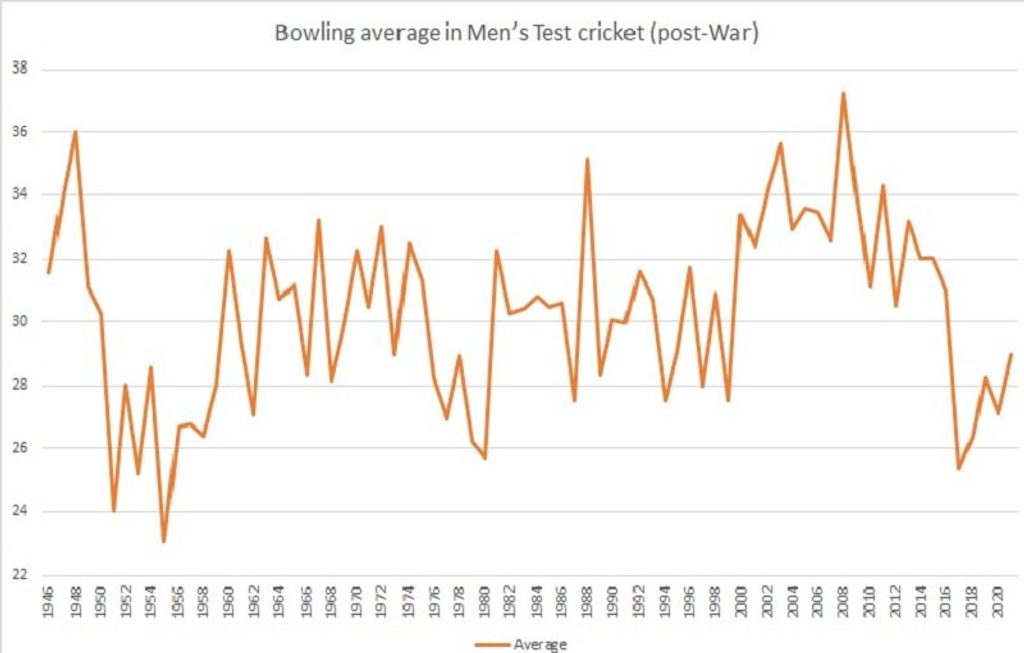

As the 1990s gave way to the 2000s and early 2010s, the batters regained upper hand. There was the odd series dominated by the bowlers, but the runs kept coming. By annual bowling average – a number that used to flirt with the 30-mark in the 1990s – now kept grazing 35.

Then, around the mid-2010s, things began to change. It is difficult to pinpoint one reason for this, but teams around the world began to boast a rounded attack where that one – let alone more than one – weak spot became difficult to find.

The weakest (fourth-best bowler) of the Australian attack, for example, is better than his counterpart from any other over the past half a century. India had a pace attack their fans had never dreamt of. Pakistan and South Africa continued with their seemingly infinite supply of fast bowlers. England found new pace-bowling stars to support their two behemoths. The New Zealand pacers gave them an aura of invincibility at home. The list is long.

The trend reversed, albeit temporarily.

Bazball

What could be done? Every batter went for what they were best at. For every Cheteshwar Pujara there was a Rishabh Pant, but there was no collective strategy. And while batting units did recover from the lows of 2017 and 2018, the average did not hit the high of the 2000s.

In the summer of 2022, England decided to repackage what batters of the 1990s used to do: they went after the third bowler and onwards. And unlike the 1990s, T20 cricket and significantly superior bats enabled the 2022 batters to take more risks, play absurd, high-risk shots. There was method to the seeming madness of Bazball, for the attacks were not random.

England, who had been redefining limited-overs batting since 2015, had the batters – Ben Stokes, Joe Root, Jonny Bairstow, Ollie Pope – to execute their plan. Even Alex Lees, even the much-maligned Zak Crawley, they all struck at over 50. They even toyed with the idea of promoting Stuart Broad to slog. The batters played out the new ball – always a threat in England – and accelerated thereafter.

In their first four Test matches of the summer of 2022 – three against New Zealand, one against India – England were up against the two attacks that had clashed at the World Test Championship final last year. Now, they not only won all four Test matches but also scored at breakneck pace.

England scored at 4.69 an over across the four Test matches, but there was a pattern to that. Their run rate was 4.01 in the first ten overs bowled with every new ball (one every innings barring the first innings at Trent Bridge, where New Zealand needed two); after that, it rose steadily to 4.82. England broke records, pulled off steep chases at unthinkable pace, sending two quality attacks in disarray.

The England batters picked their bowlers well. Trent Boult (16 wickets at 28.93) and Kyle Jamieson (six wickets at 27.50), the only two New Zealand bowlers to average under 30, were also the only ones to go for under four an over. Even Tim Southee conceded runs at 4.32.

India played only one Test match, but the difference there was stark. Of the four fast bowlers, Jasprit Bumrah and Mohammed Shami went for under four an over, while Mohammed Siraj and Shardul Thakur at over six. This seems easier said than done, for in the 2021 leg of this curious series-in-two-parts, Siraj had 14 wickets at 30.71, and Thakur seven at 22. As a result, Bumrah and Shami ended up bowling significantly more and, thus, got less rest between spells, than they would have wanted to.

Then came the South Africans. England stuck to the same plan, but Marco Jansen and Anrich Nortje were not easy to get away after Kagiso Rabada and Lungi Ngidi had their way. Taller than their New Zealand and Indian counterparts (to be fair, Jamieson did brilliantly until his injury), the South Africans had troubled the Indians earlier this year, and the New Zealanders in New Zealand.

England still scored at 4.02 once they saw off the new ball, but they lost wickets too frequently. Even Root, Bairstow, and Stokes – their heroes of the summer – could not provide the impetus they needed.

England seemed to play with caution in the second Test match, at Old Trafford. Their run rate, 3.89, was at par with their second-innings rate of 3.96 at Lord’s. However, they were coming off an innings defeat, and Old Trafford has been the slowest-scoring of all English Test venues. In their entire history, only twice have England scored at over 3.89 in a match in Manchester.

South Africa’s decision to pick Simon Harmer ahead of Jansen backfired as Ngidi never seemed to threaten, allowing the England batters to take on Rabada and Nortje as the innings wore on. England mixed caution with Bazball to secure an enormous lead and level the series. Whether they will continue with it in the long term is something to be seen, but as of now, their season record stands at 5-1 immediately after they had won one out of 17 Test matches.