KKR’s Sunil Narine has failed to land the killer blows required of a pinch-hitter so far this season. CricViz analyst Ben Jones takes stock of the mystery spinner’s troubles with the bat.

New Year’s Day, 2017.

David Hussey’s Melbourne Stars are taking on Aaron Finch’s Melbourne Renegades. As captain Finch walks out to open the batting, the man alongside him is not Marcus Harris, as it has been for the first two matches of their season. Instead, it is their overseas mystery spinner, Sunil Narine. A man who has never opened the batting before in a T20 match, promoted up the order to give it a swing, to go hard for a good time, not a long time. Narine bashes 21 (13), a crucial injection of energy at the top of the order, and the Renegades eventually win.

Open Account Offer. Up to £100 in Bet Credits for new customers at bet365. Min deposit £5. Bet Credits available for use upon settlement of bets to value of qualifying deposit. Min odds, bet and payment method exclusions apply. Returns exclude Bet Credits stake. Time limits and T&Cs apply. The bonus code WISDEN can be used during registration, but does not change the offer amount in any way. Bet on the IPL here. 18+ please gamble responsibly.

It was an experiment the Renegades only repeated twice in their next five matches, but this was barely the beginning for Narine. Three months later, in Kolkata Knight Riders’ third game of the season, Narine opened the batting again. This time, he went bigger, 37 runs from 18 balls against Kings XI Punjab, and one of the most significant tactical moves of the modern era was cemented. Sunil Narine was now a pinch-hitter.

The pinch-hitter is one of the most underused tactics in T20 cricket. In the Powerplay, the value of wickets is normally high, and the value of runs relatively low, so teams prioritise bowling their best bowlers in this phase. If you send in a pinch-hitter – a player whose wicket value is inherently lower than a classic anchor batsman – then you have the opportunity to exploit the field restrictions, but without the significant downside that comes with losing a wicket.

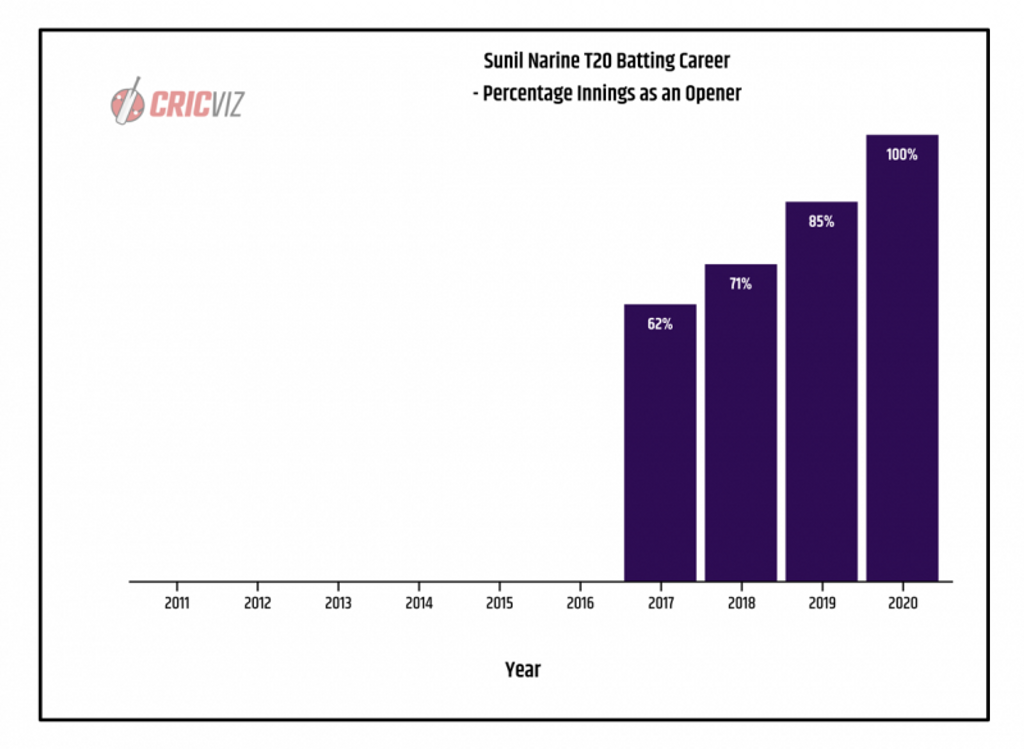

Yet like all theories, it takes practical examples to persuade people, and over the next few years, Narine became a template. He has opened in 36 of his next 42 innings for KKR and become the hallmark of what a T20 pinch-hitter can be. His average innings, just over 11 balls, is the shortest of any established opener in the world, but his scoring rate is the fourth-fastest. Walk in, whack it, get out, job done.

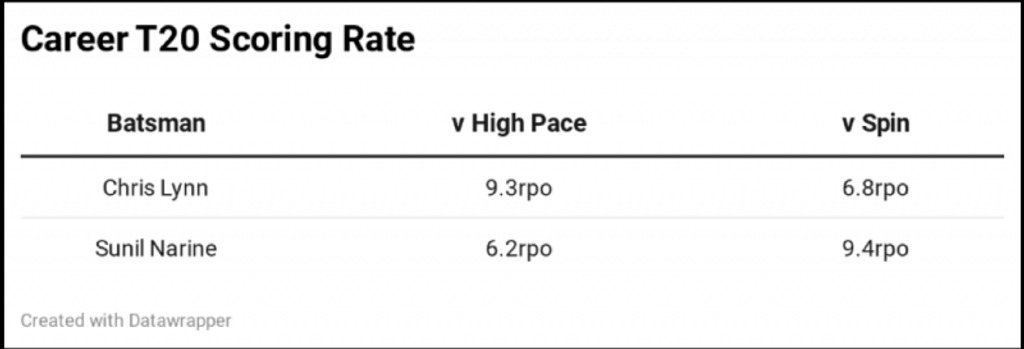

The fundamental reason for Narine’s effectiveness in this role over the last few seasons has been his brilliance against spin. In the last four IPL seasons, he’s scored at 13rpo against spin bowlers. That’s a strike rate of just under 220 in old money, and significantly faster than every other IPL batsmen in that time.

The flipside to Narine’s spin strength is that he really can’t play pace, this pronounced weakness the main reason why he’s never gone on to be considered a ‘proper batsman’. While he still scores quickly against seamers overall, against high pace bowling Narine scores at just above 6rpo.

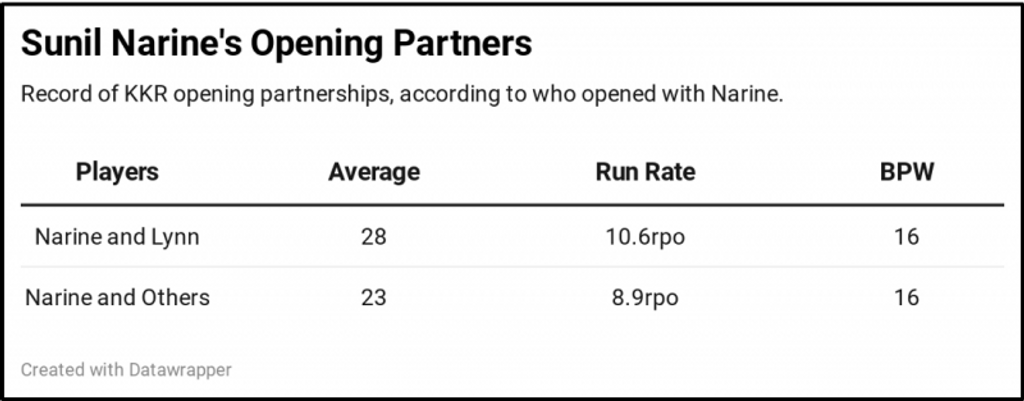

KKR didn’t mind this though. If anything, it made Narine opening more alluring, given his usual opening partner. Typically Narine was opening alongside Chris Lynn, a batsman who had almost completely inverse qualities. Lynn was completely elite against pace, but very weak against spin. As such, teams were nervous to bombard Narine with the pace they knew could limit him, fearing he’d get an early single and unleash Lynn’s attacking ability on their seamer.

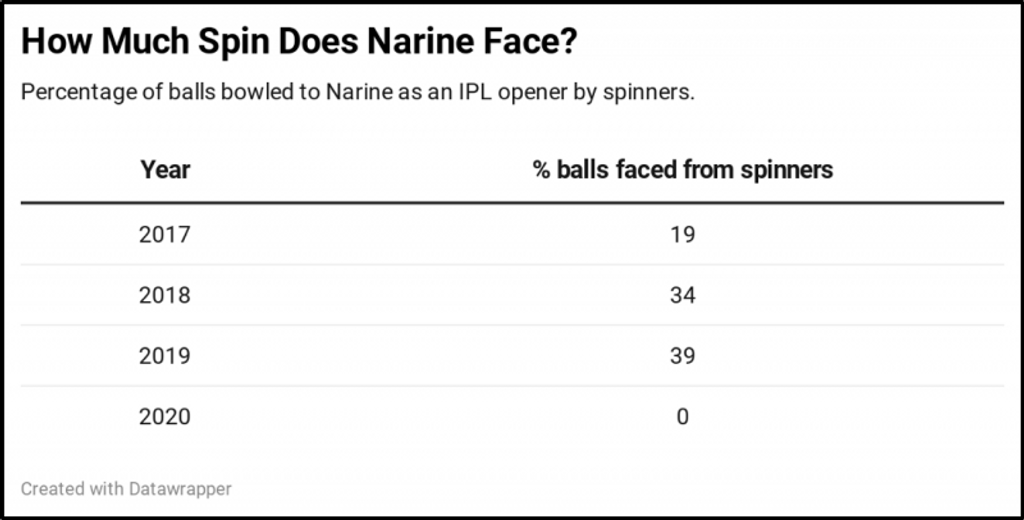

This season, Lynn has moved from Kolkata to Mumbai, and Narine’s batting has struggled. With scores of 9 (10), 0 (2), 15 (14) and 3 (5), and it’s no surprise to see that Narine is yet to face a delivery of spin in the 2020 IPL. Analytics is not as ubiquitous, and trusted, as many would believe or suggest, but even the most old-school side makes sure to cover the basics; teams are hyper-aware of his power against the slower bowlers and have managed to completely deprive him. It’s cut off his oxygen, and it has coincided with the first season to date where the strategy of promoting Narine has not worked.

Shubman Gill is clearly a very talented batsman, and will improve against pace, but currently his most notable strength is his game against spin. His average and scoring rate against spin (63.25 and 8.2rpo) are both superior than the equivalents against pace (30.61 and 7.4rpo). No issue for Shubman himself, and the youngster is clearly a far better player against pace than Narine is, but the consequence of batting them both together is that teams have no disincentive to just bowl pace – ideally high pace – from the outside. Previously, Lynn acted as a protective barrier, and that barrier is no longer there. That mutual protection that Lynn and Narine had together, their respective strengths covering the other’s weakness, brought out the best in them both.

KKR don’t have to stay wedded to this strategy. Narine obviously makes the first XI with his bowling alone, and so they only really need to rejig the order. The likely replacement for Narine, were KKR to move him down, would be Rahul Tripathi, who made 36 (16) on Saturday night. You’d be foolish to act on the basis of a single innings, but moving to a more traditional structure – with Tripathi opening alongside Gill, with Narine at No.8 – feels ever more inviting. Tom Banton, resting on the bench as the young overseas, represents similar explosiveness to Narine but with the opposite skillsets, a strength against pace which could benefit Shubman.

KKR will be, and should be, extremely proud of what they have achieved with Narine over the last few years. They have taken arguably the best T20 bowler in the world and squeezed yet more value out of him, finding every last drop of cricketing ability within him and finding a home for it, spotting a place where it can be put to work. There is an understandable desire to stick with that innovation, to make it work again as it has worked before. Yet moving on now is not failure; reverting to tradition is not conservativism. It’s natural.

There is a life cycle to all strategies. The Stars captain trying to control Narine in that Melbourne Derby, David Hussey, is now Narine’s batting coach at KKR. Three and a half years in a sport as young as T20, where tactical developments happen rapidly, is an awfully long time. That applies to individuals as much as it does to broader, structural ideas.

The next stage in Narine’s batting cycle does not have to be a return to the tail. As one cycle of innovation ends, another begins; if KKR want to maintain their reputation for strategic creativity, then there are other options. Narine’s strength against spin is still there, and that is valuable. Using him in the middle overs, against sides who bowl spin consistently through the middle, could have significant benefits. Sides would be forced to either take their medicine, and concede some expensive overs of spin, or to bring back a seamer to target Narine’s weakness. This could move those high pace bowlers away from being able to target Eoin Morgan, whose short-ball-issues are well documented. It could force opposition captains into using spinners, orthodox spinners, later in the innings when Morgan and Andre Russell have full license. There is still an opportunity to use Narine as a disruptor, a spanner in the works – it’s just that this opportunity may no longer be in the Powerplay.

One of the wonderful things about T20 cricket, compared to the other formats, is that the template for success is constantly being re-written. Test cricket may demand huge scrutiny for microcosmic tactical details, but basically, everyone knows how to win. The difficulty is in producing the players to execute that plan. T20, young and unknowable and volatile, is there to be explored, prodded and poked, tested and examined.

Experiments like Narine opening have made the sport richer and more sophisticated but come with no obligation to fundamentally alter the fabric of the game. This is now just another way of winning, another thing on a list. However, increasingly you feel like KKR may want to cross this one off, and move on.