CricViz analyst Ben Jones delves into the numbers to explain the benefits of right-hand/left-hand combinations at the crease.

The concept of the right-hand/left-hand combination being beneficial for the batting side is nothing new. In first-class cricket, the received wisdom was that having to chop and change between bowling to right and left-handed batsmen meant the bowler couldn’t get settled on a line and length. In T20 cricket, while that is still seen as a plus for the batsmen, the most commonly cited benefit of the right-hand/left-hand combination is to negate matchups. By having a right-hander and a left-hander together at the crease, it’s harder for sides to target a batsman with the ball spinning away; an off spinner attacking a lefty is ideal, but they’re only a single away from bowling to a righty.

There was quite a to-do when AB de Villiers kept being moved down the order for Royal Challengers Bangalore, because Mike Hesson et al were concerned about having two right-handers in the middle. Surely this was overthinking things, was the voice from one side of the aisle, while the other applauded RCB’s commitment. Sam Curran’s position has been up for discussion throughout the season, with Chennai Super Kings’ lack of left-handers making him the sole option were they to focus on trying to get those DHPs (Different Handed Partnerships) earlier on in the innings. Some teams have stuck rigidly to the tactic – at the start of this season, Delhi Capitals were rotating Shreyas Iyer and Shimron Hetmyer at No.3 and No.4, with either coming in first drop depending on whether Prithvi Shaw (RHB) or Shikhar Dhawan (LHB) fell first.

But is there actually any benefit to this tactic? Well, it’s hard to definitively say, but the numbers are there to explore – and so explore we shall. For ease of reference, we will refer to RHB/LHB partnerships as DHPs, and both RHB/RHB and LHB/LHB partnerships as SHPs (Same Handed Partnerships). To keep it comparing apples with apples, we’ll be looking only at partnerships involving batsmen Nos. 1-7 in the order.

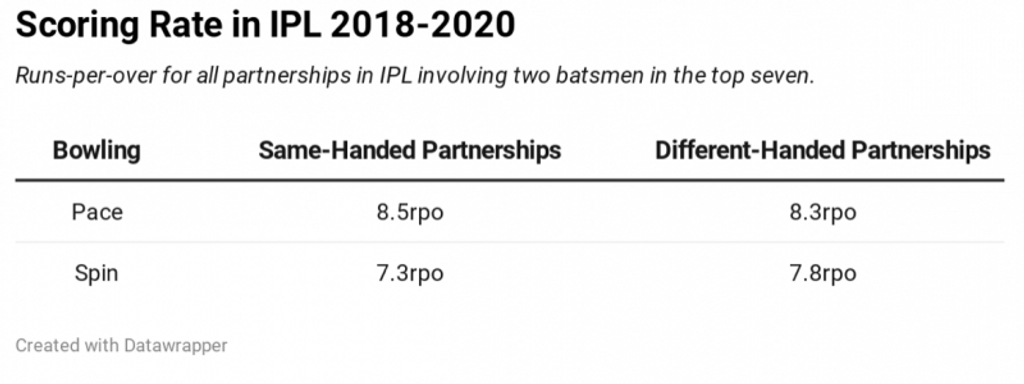

So, on the face of it – no, there’s no substantial benefit. DHPs score a fraction quicker than SHPs, score about 1.5 runs more across the length of the partnership, and hit a fraction more balls to the boundary.

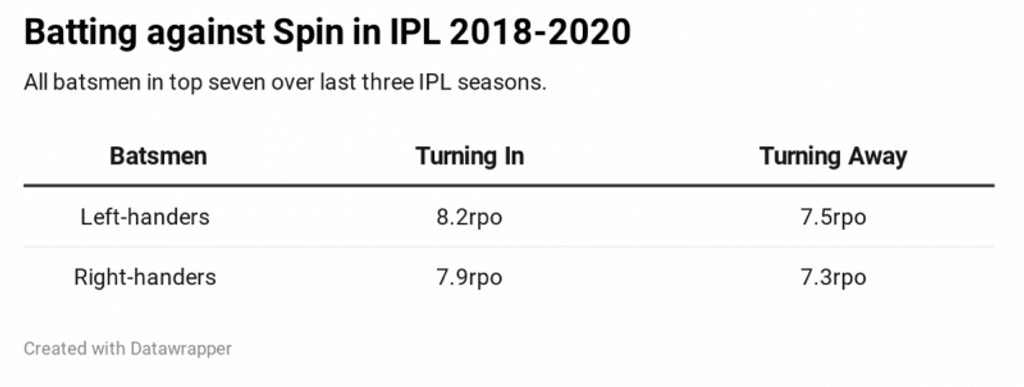

However, when we break this down a little further, we can spot some more interesting trends. As we have outlined, the primary (cited) benefit of the DHP is the ability to manage match-ups, but specifically match-ups against spin. There’s clear evidence that having differently-handed batsmen together at the crease makes a substantial difference to scoring rates against spin.

It’s no surprise then that when you look at the comparison of batting partnerships only against spin bowling, we see a much greater disparity. DHPs score substantially quicker against spin, than SHPs, and hit considerably more boundaries. They don’t last as long in the middle, but the increased scoring rate accounts for that.

The most obvious reason for this is that batsmen in DHPs face more of the bowling they want to. In a SHP, 25.2 per cent of the balls batsmen face from spin are good match-ups for them (i.e. the ball spinning in), while in DHPs that figure rises massively to 50.5 per cent. The received wisdom, that idea of it being harder for a captain to just bombard a player with the ball turning away when opposing hands are at the crease, is backed up in the data.

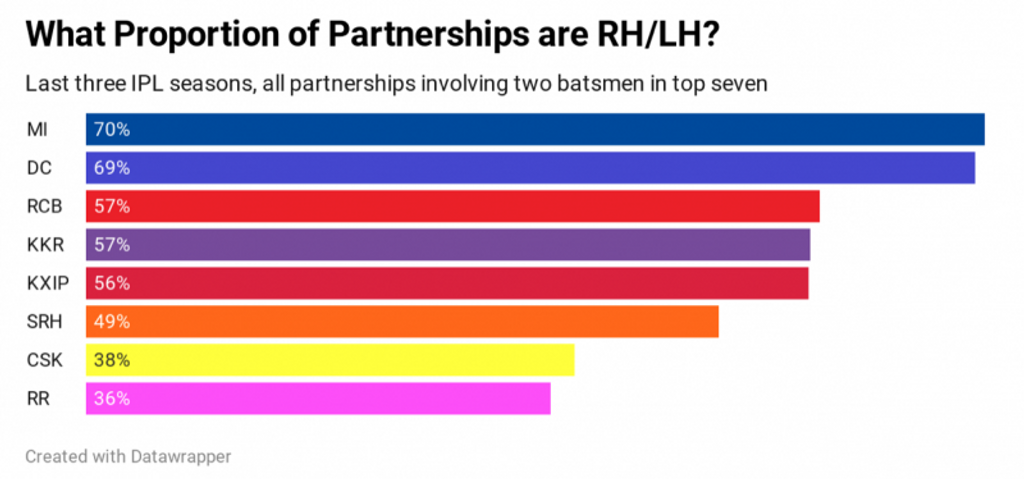

And so, having established that there is some advantage to having right-handers and left-handers batting together, it’s natural to ask – which teams do it best?

In the last three seasons of IPL cricket, Mumbai have been the side to use RH/LH partnerships more than any other side. 70 per cent of their partnerships for the (first five wickets) have been DHPs. That could of course be nothing more than having quite a few prominent left-handers in their set-up, with Quinton de Kock, Krunal Pandya and Ishan Kishan all playing a lot of matches in the last three years. However, that’s not the case – just 16 per cent of Mumbai’s balls faced (for the top seven batsmen) have been by left-handers, the lowest figure of any side. MI get huge credit for their management of match-ups, credit which is sometimes difficult to find hard evidence to support, but this is just that. MI have used their resources very effectively in order to get this advantage, something for which they deserve huge credit.

So next time the importance of RH/LH partnerships is cited, it’s worth remembering that a) they’re more important against spin than pace, and that b) they’re more important for scoring quickly than building long partnerships. There is value in them, but probably not to the detriment of simply having a better player in the middle, and over-reliance on it as a tactic could be counter-productive.