Since they were pooled together at the top in February 2021, Babar Azam and Mohammad Rizwan have formed a solid opening partnership for Pakistan. However, worrying trends have emerged of late, writes Abhishek Mukherjee.

In early 2021, South Africa toured Pakistan for – along with other formats – three Twenty20 International matches. The series marked the first instance of Babar Azam and Mohammad Rizwan opening batting for Pakistan in the shortest international format.

Rizwan scored 197 runs at a strike rate of 146, but Babar dropped to No.3 after two failures. The self-imposed demotion was a stopgap arrangement, for they reunited when Pakistan toured South Africa a month later.

South Africa posted 203-5 in Centurion, Babar (122 in 59 balls) and Rizwan (73* in 47) added 197 in 106 balls to drive Pakistan to an 18-over win. That partnership – followed by an 88-ball 150 against England in Trent Bridge – ensured that Pakistan went into the 2021 T20 World Cup with Babar and Rizwan at the top.

The plan has worked for Pakistan to some extent. In barely a year and a half (and 29 matches), Babar and Rizwan have added 1,333 runs – a tally that has been bettered by only four other opening pairs. With a 1,000-run cut-off, their average of 47.60 is the second-best. Their five century stands (four of which are in excess of 150) are a world record.

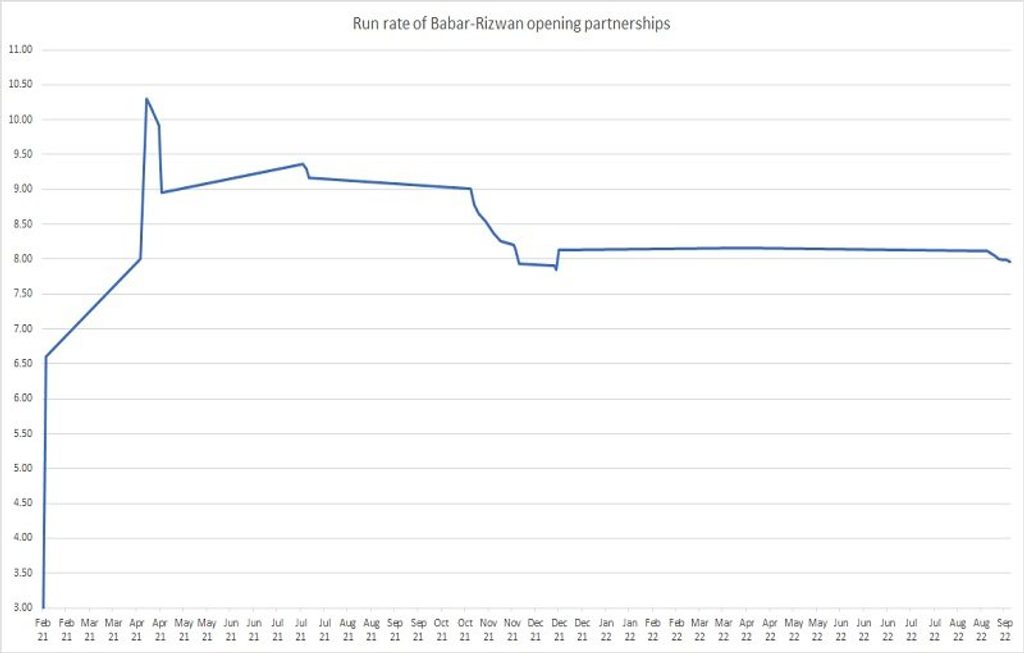

These are fantastic numbers – only if one ignores that pesky scoring rate. While opening batting together, Babar and Rizwan have scored at 7.96 an over. With a 700-run cut-off, they are the slowest opening pair in the history of T20 Internationals.

Of course, this has not happened in a day. The strike rate stood at a reasonable 8.52 until Pakistan’s famous 10-wicket win against India in last year’s T20 World Cup. In the euphoria of that win, forgotten were the stands that followed – 28 in 31 balls against New Zealand, 12 in 15 against Afghanistan, 35 in 37 against Scotland, and 71 in 60 against Australia.

Pakistan played in Bangladesh a week later, where Babar and Rizwan added 60 in 73 balls – not the other way round – across three matches. Barring the odd burst, things did not improve: since that chase against India, the Babar-Rizwan stand has scored at 7.12 an over – a solid 20 per cent drop from what it used to be.

Babar Azam-Mohammad Rizwan opening partnerships

Babar Azam-Mohammad Rizwan opening partnerships

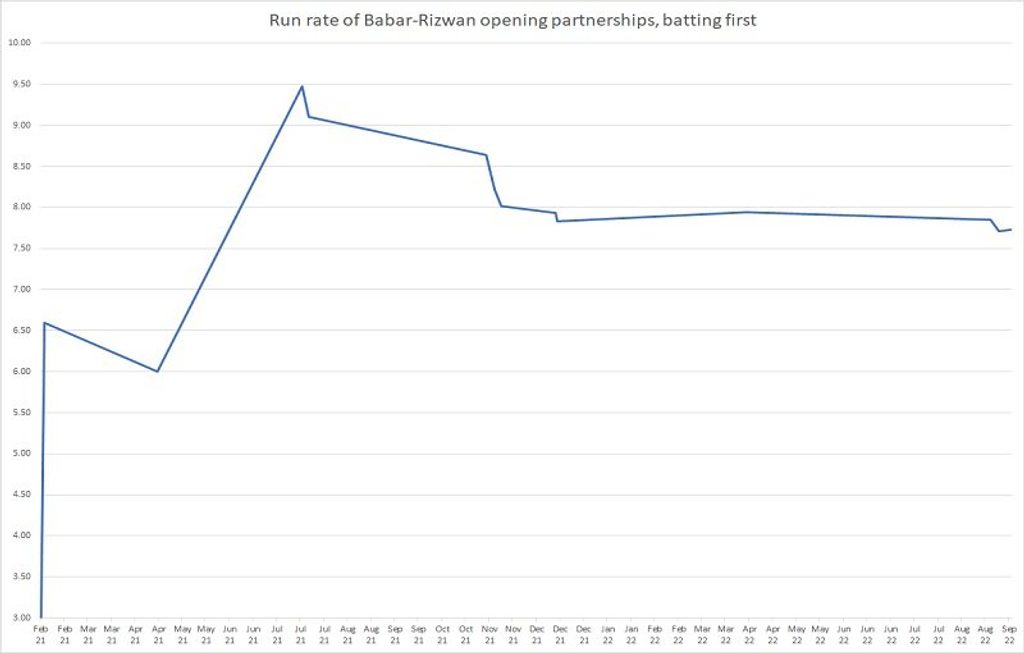

Of course, it is not fair to dismiss two batters of such talent based on simple run rate. One needs to dig deeper. But then, while batting first, without a target in sight, the Babar-Rizwan opening pair scores at 7.73 – slower than their overall record. Since the start of the 2021 T20 World Cup, it drops to 7.09.

Babar Azam-Mohammad Rizwan opening-partnerships while batting first

Babar Azam-Mohammad Rizwan opening-partnerships while batting first

But this merely sums up what Babar and Rizwan do until one of them gets out. How have they done individually?

As opener, Babar has scored 1,980 runs at 132 and Rizwan 1,758 runs at 131. They are the fourth- and fifth-slowest openers in the history of Twenty20 Internationals. Of the three men above them, Tamim Iqbal and Tillakaratne Dilshan have retired, while Shikhar Dhawan last played in 2021, for a second-string side.

Since they joined hands at the top that day in Lahore, Babar has struck at 129 and Rizwan at 131, numbers not too different from their career records as openers. For perspective, Jason Roy (130 over this period) and Ishan Kishan (133) have been left out of their respective squads.

To have one batter at the top batting at that pace can stall a team’s acceleration. To have two can hit them hard. While opening batting over the same period, Babar has scored 30 per innings, off 23 balls, while Rizwan’s efforts have amounted to 49 in 38. Between them, they have about 80 runs in 10 overs – in other words, half the innings.

While it may be argued that Babar and Rizwan enable Pakistan to have wickets in hand, the resource is bound to yield diminishing returns as the other resource – balls – run out. Things may go further downhill if a middle-order batter – Iftikhar Ahmed in the Asia Cup final, for example – gets stuck.

At this point, Pakistan need to strike a balance, for as the Asia Cup demonstrated, the current method has significant demerits. They need at least one of Babar or Rizwan to abandon their current self – being amazingly gifted, both are capable of doing that – or tweak their top order.

Time is running out.