The last 11 teams batting first in a knockout match at the T20 World Cup have all lost. As Abhishek Mukherjee explains, this is not a coincidence.

Mirpur, 2014. Chasing 161 against Sri Lanka in a T20 World Cup semi-final in Mirpur, the West Indies were quickly reduced to 34-3 in 7.1 overs. Time was running out, more so because Kalboishakhi, the devastating Nor’Wester storm that is so common in the area in that time of the year, loomed large.

Dwayne Bravo hit out before perishing, and with his departure came rain, accompanied by a menacing hailstorm. The West Indians batted deep, until Sunil Narine at No.9, but none of that mattered anymore. Sri Lanka, 26 runs ahead on the Duckworth-Lewis par score, avenged their defeat in the final of the last edition.

It was also the last time a side batting first won a knockout match at the men’s T20 World Cup. Since then, all 11 teams have lost. Of course, one may wonder whether the sample size is too small to draw a conclusion from. Over the same period in T20 World Cups – in other words, the league matches in the 2016, 2021, and 2022 editions – the teams batting first have won 57 times and lost 53. There is no pattern here.

Perhaps it is not a coincidence, then.

The trend

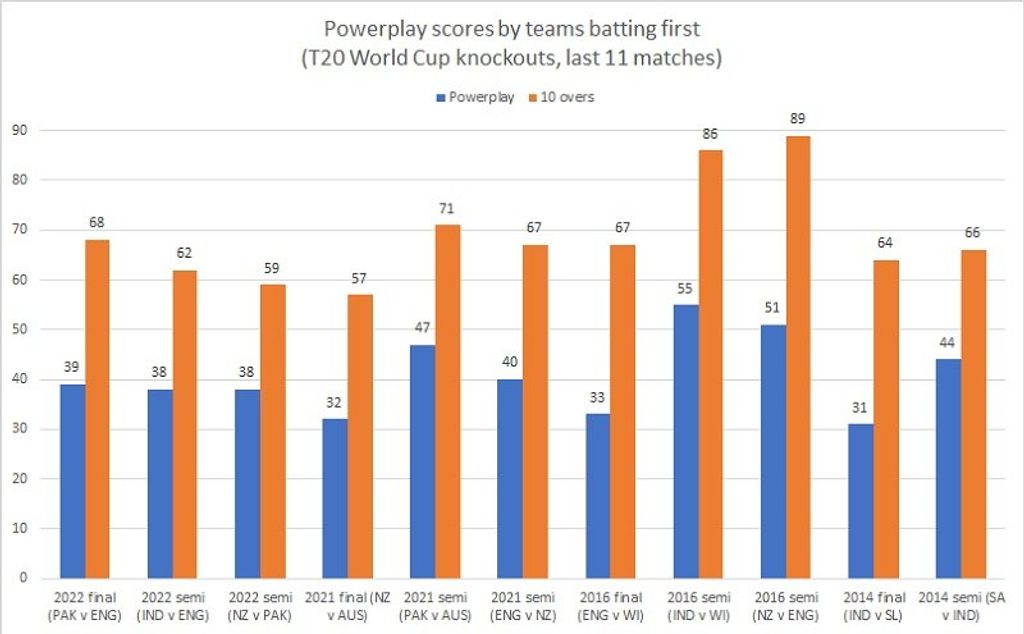

The pattern is unmistakable: in almost every instance, the side batting first has waited until late in their innings, at least the second half, before accelerating.

In nine of the matches, the side batting first scored 47 or fewer (in other words, scored at under eight) inside the powerplay. After 10 overs (halfway through the innings) none of these sides went past 71.

There were two exceptions to this – the two semi-finals of the 2016 edition.

New Zealand’s 51-1 in the powerplay against England in Delhi seems reasonable, as does the 89-1 after 10 overs, when pitted against the nine matches mentioned above. Yet, the conditions were so batting-friendly that England reached 67-0 and 98-1 at the same points to complete an easy chase.

India amassed 55-0 in the powerplay against the West Indies in Mumbai, but slowed down en route to 86-1 after the 10-over mark. West Indies, 44-2 after the powerplay later that night, continued to hit and almost covered the gap to reach 84-2 after 10 overs.

It is not that they lost early wickets. In only two of these 11 matches did the side batting first lose more than three wickets inside 10 overs. Of them, only England (in the 2016 final against the West Indies in Kolkata) lost three inside the powerplay.

The Kolkata match is also one of two instances of the chasing side falling behind the team batting first at the powerplay. In the other, in Abu Dhabi in 2021, New Zealand responded to England’s 40-1 with 36-2. It took an exceptional burst (57 runs in three overs) for them to win that night.

To sum up, despite there being no pressure of wickets, the sides batting first refused to accelerate, leaving the onslaught for the second half. They have failed, not once or twice but 11 times on the trot.

‘Big matches’

Throughout history, it was almost always considered better to bat first in unlimited-overs cricket (for lack of a better term). Since matches used to be longer, pitches would deteriorate over time. WG Grace’s quote on the decision to bat first irrespective of conditions (“When you win the toss, bat. If you are in doubt, think about it, then bat.”) might have been a myth (or not), but one can see the logic.

Then came World Cups, the only tournaments where every major cricketing nation played. Winning a World Cup brings glory, and they happen once every four years. Over time, matches at the end of the World Cup – played in knockout format – began to bear the tag of ‘big matches’.

Sports psychologists may be able to explain the whethers and whys better, but testimony from the participants often point towards the hypothesis that “big matches” put cricketers and teams under more psychological pressure than other matches.

Combining the two, batting first does seem an easier choice in ‘big matches’.

At the same time, there is a distinctive disadvantage to batting first in limited-overs cricket. The chasing side knows how many to score. The team batting first is left to guess how to pace the innings, not an easy task in a World Cup where every day brings a new opposition on a new venue. The chasing sides, on the other hand, know – and not estimate – how many they need.

In a 50-over match, the batters can play themselves in, put up a big score, and turn the tables around. In a 20-over match, the they do not have that luxury. Yet, the pressure of the ‘big matches’ perhaps forces them to assume their 50-over avatar.

By the time the onslaught begins, a quarter of the match is gone. Unless the sides batting first begin to take on the bowlers earlier in the innings, the streak is likely to stretch beyond 11 matches.