The 2022 edition, in Australia, is the best men’s T20 World Cup ever, and that has been on the cards for some time, writes Abhishek Mukherjee.

What makes a great World Cup? Excellent batting and bowling – and, of course, fielding – are obvious parameters, but that holds for any cricketing tournament. For a World Cup to qualify as outstanding, it needs to live up to its name, particularly that italicised word.

The ICC may have only 12 Full Members, but the seven T20 World Cups have witnessed six champions across four continents (five, if you consider that Guyana, part of the West Indies, is in South America). The tournament features 16 teams at this point, and will expand 20 in its ninth edition. For perspective, the FIFA World Cup did not cross the count of 16 until its 12th edition, in 1982.

But that is about the tournament strength: have the matches inside the tournaments been competitive enough? Or has the lopsidedness made them too dependent on the ‘Big’ matches for success?

However subjective ‘greatness’ may be in cricket, the outcomes have – since the inception of the sport – been determined by numbers. In limited-overs cricket, the team batting first wins by the number of runs they outscore the opposition by, while the chasing side wins by a number of balls to spare.

Of course, the number of wickets left is a relevant parameter as well – you cannot win a chase if you get bowled out – but in teams seldom get bowled out in Twenty20 cricket. Over time, that parameter has lost relevance to the extent that it does not determine the position of teams on the points table anymore: the net run rate, the second-most important criterion, does not deal with wickets at all.

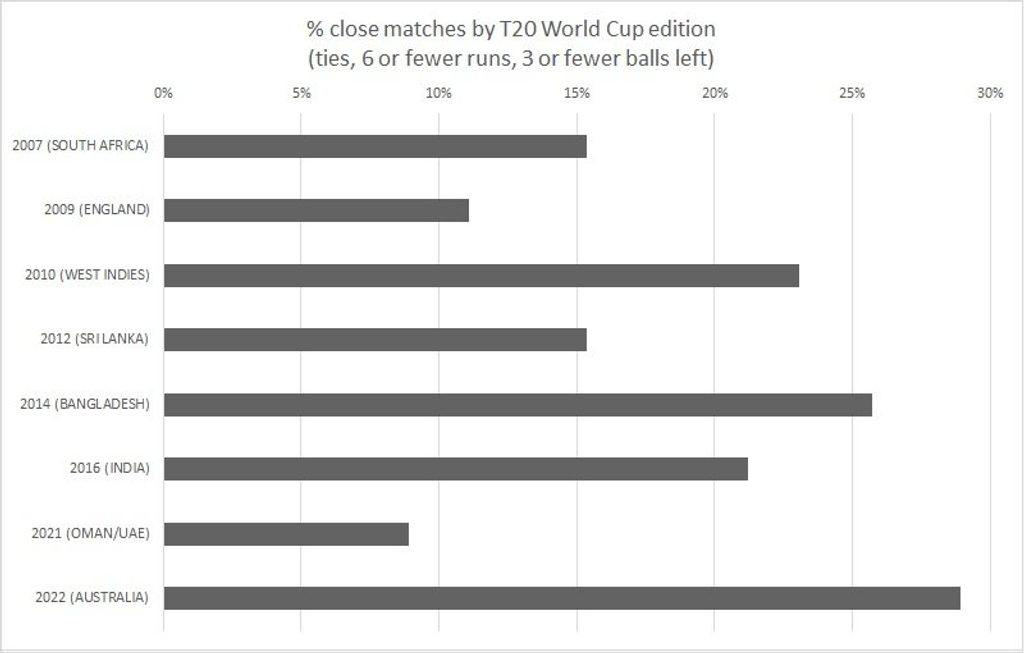

Let us now try to define close matches. A tie is obviously the closest possible outcome, so they qualify. For runs, let us put the cut-off at six runs – in other words, a hit away from a tie.

Unfortunately, there is no such obvious solution for the number of balls left: the count of three balls is perhaps arbitrary, but the outcome does not change significantly if it is altered to two or four.

At 28.9 percent, the 2022 edition in Australia has had the best share of close matches. The Bangladesh edition in 2014, the other edition to cross the 25-percent mark, had about 12 percent fewer.

The 2022 edition looks perhaps even more spectacular because the tournament had been put on hold for five and a half years, between 2016 and 2021 – a substantial gap for a 15-year-old World Cup. Upon return, it produced the tournament with the least proportion of close matches – 8.9 percent.

The 2022 edition would have stood out anyway: the trebling of tight finishes compared to the previous edition, played only a year ago, compounded the feeling.

But that is only part of what makes the 2022 edition special.

Across the first four editions of the T20 World Cup, there had been only two instances of an Associate Member defeating a Full Member: the Netherlands stunned England, and Ireland beat Bangladesh, both in 2009.

The count rose to three in 2014 before dropping to two for each of 2016 and 2021. In 2022, we have already had four such instances: Namibia defeated Sri Lanka, Scotland triumphed over the West Indies, and the Netherlands beat Zimbabwe and South Africa to secure a berth for the 2024 edition.

The above list does not include Zimbabwe’s win against Pakistan or Ireland’s against England – all four are Full Members – but probably should, given international cricket’s step-motherly treatment towards the two triumphant sides.

But even that is not all.

That the tournament was set to be special was determined in the First Round, where there was no clear dominant side. All eight teams won at least one and lost at least one match. Afghanistan were the only team to return home without a win, but they got to play only three matches. Until the last day, no one knew which two of five teams would qualify from Group 2, while Group 1 remained a tripartite struggle until the end (the teams were separated only by net run rate).

Yet again, the edition stood out in contrast with 2021, where the points table both groups of the First Round read the usual, hierarchical 6-4-2-0, while Group 2 of the Super 12 ran 10-8-6-4-2-0. Until the knockouts, only the three-way contest in Group 1, featuring England, Australia, and South Africa, produced some competition.

Here, too, 2014 produced perhaps the closest contest to the intensity of 2022. The two groups in the First Round returned 4-4-2-2 and 4-4-4-0, while Group 1 of the Super 10 ran 6-6-4-2-2. It was only Group 2 that turned out to be one-sided.

What changed this time?

Cricket stands on the verge of one of the most significant moments in its history. The traditional geopolitical structure is giving way towards a franchise-driven model.

There are many merits and demerits of that, but there is little doubt that it brings cricketers from Associate Nations to the forefront more than ever. Until franchises began to dominate cricket, there was virtually no possibility of a cricketer from an Associate Nation to rise to stardom.

Of course, they could play domestic cricket in another country – England, mostly – but they would be forever deprived of matches against the top teams.

Franchise cricket changed that. Cricketers from Associate Nations can now hone their skills in as many leagues as their counterparts from the Full Members. They may not play the Full Members as teams, but they do play their individuals as individuals throughout the year, matching them in skill.

It was only a matter of time before they matched them in skill as units as well. It could have taken place in 2021, after a five-and-a-half-year gap in a format that keeps changing at a rapid rate. It took a year longer.