Has the pitch generally got trickier to bat on as the game has progressed during the Cricket World Cup? Can we confidently label any pitch a flat belter or a minefield? Ben Jones draws some interesting conclusions using CricViz’s PitchViz model.

It might have been missed, amongst the excitement and stress but England versus New Zealand on Wednesday was a very, very odd game of cricket.

At the start of the day, Jonny Bairstow and Jason Roy went to town. They charged out of the blocks in the manner to which we’ve become accustomed, battering 123 unbeaten runs in 18 overs of a yet another firecracker opening partnership. It was nothing new, their third consecutive opening stand of the tournament, but given the moment and the necessity that England win, it felt thrilling.

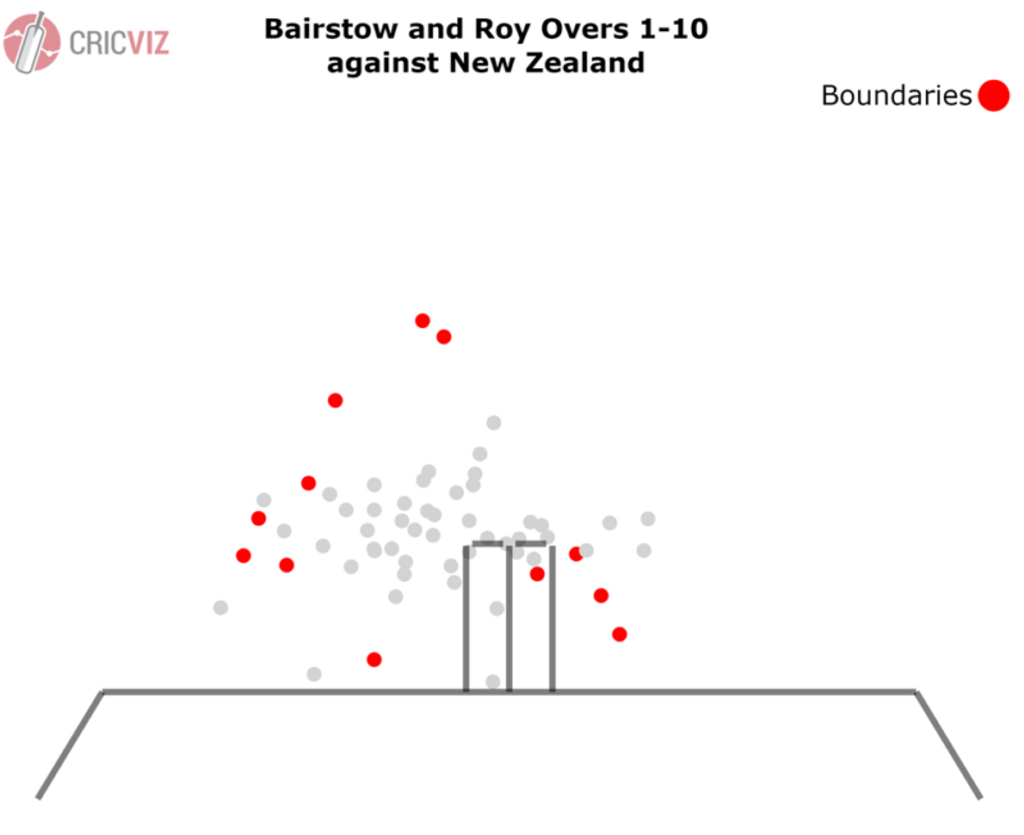

Yet whilst these swashbuckling starts can sometimes tense – as if England’s openers are playing a game of Russian Roulette with the opposition attack – that wasn’t really the case in Durham. Aside from a few nervy swipes against Mitchell Santner in the opening over, they didn’t do anything too outlandish, attacking only when the seamers were too wide, too full, or too straight. Roy and Bairstow are very good at making calculated gambles when taking down the new ball, but on this occasion they didn’t really need to. Seemingly, a very helpful pitch was doing a lot of the work.

“God, it looks like a road.”

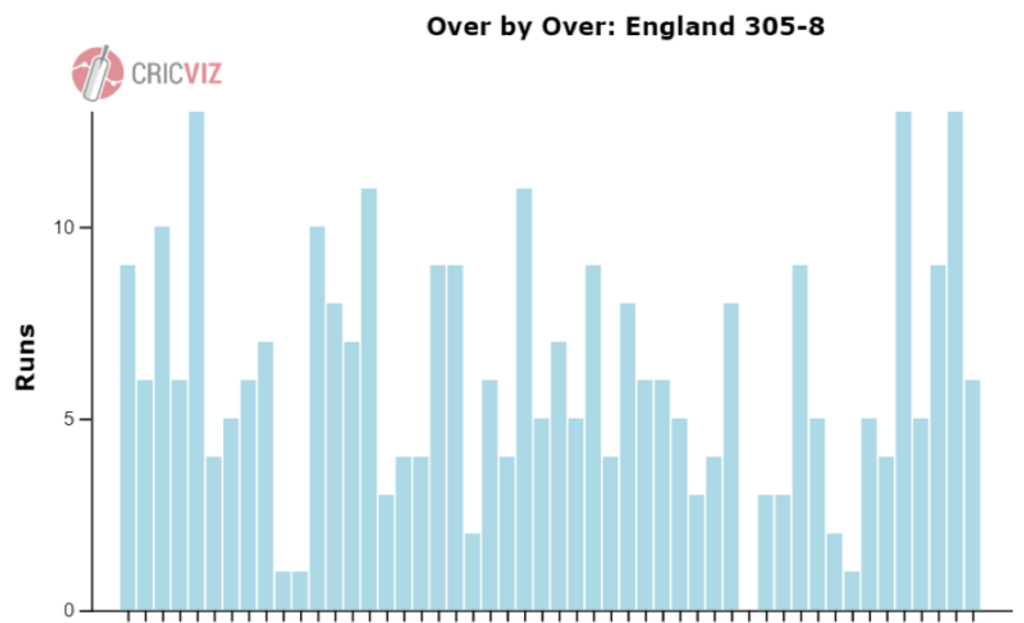

Then everyone else had a go on that pitch, and things seemed a little different. The rest of England’s line-up, filled with power-hitters and free-scorers, struggled to get the ball off the square. They ticked things over for a while, before really stumbling in the 31-40 over period, collapsing to a nerve-inducing 305.

At the halfway point, it felt like England had thrown away a good start on a pitch where 325 was par – there were plenty of frightened faces in the crowd, and perhaps even in the dressing room.

Then New Zealand came out to bat and the nerves began to seep away. The surface seemed to still be tricky, the ball still not coming onto the bat, and surviving – let alone scoring at seven runs per over – looked a challenge. Some lucky dismissals enhanced this atmosphere, but the pattern of the game had completely inverted.

“God, it looks like a minefield.”

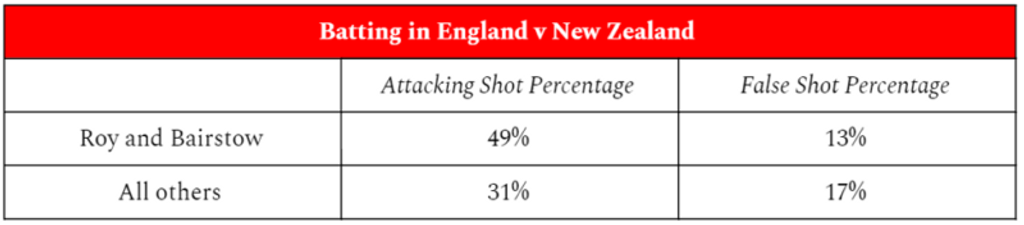

The game seemed to have been split in two – before and after that opening partnership. It was like watching two different matches. Bairstow and Roy had attacked more than everyone else, but had been more secure in their strokes.

It felt on the face of it like England’s openers had been playing on a different pitch.

That’s because, in effect, they were.

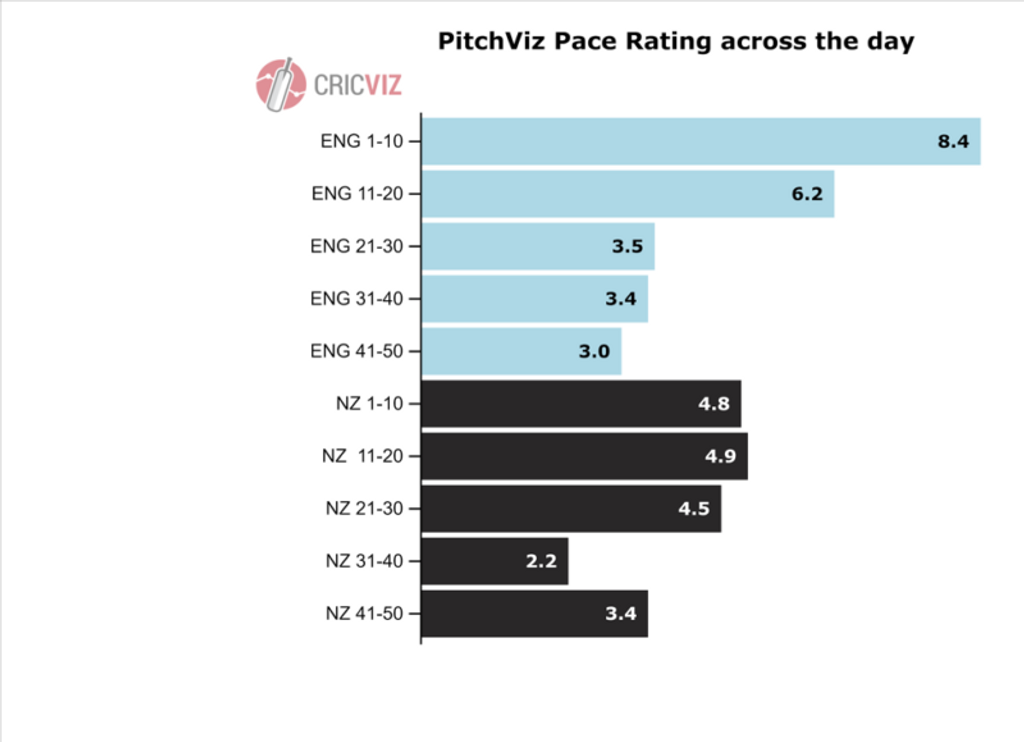

CricViz’s PitchViz model assesses the characteristics of individual pitches using historical ball-tracking data, and plenty more besides. One of the characteristics it assesses is the “pace” of the pitch, and thus how easy the ball is coming on, by giving it a rating out of 10 – the higher the number, the quicker the pitch.

According to the model, for the first 20 overs on Tuesday, when Roy and Bairstow were taking the new ball down, the pitch was playing as quickly as it would all day. From that point onwards, it began to slow up, making it harder to time strokes and force the scoring rate upwards. Roy and Bairstow made the absolute most of it, but they were gifted the best of the conditions.

There’s been a lot of chat about the various strengths and weaknesses of each team on different kinds of pitches. England have been labelled ‘flat-track bullies’, whilst India have been criticised for not being able to hack it when the pitches are higher-scoring. There’s some truth in the both assessments, even if the vitriolic tone of those who offer this criticism doesn’t suggest a particularly deep level of thought on the subject.

However, games like we saw on Wednesday provoke the question of whether it’s fair to characterise pitches – and teams – so broadly? Is it fair to say a pitch is “flat” if that pitch can change so considerably throughout the day, as it did at Durham this week?

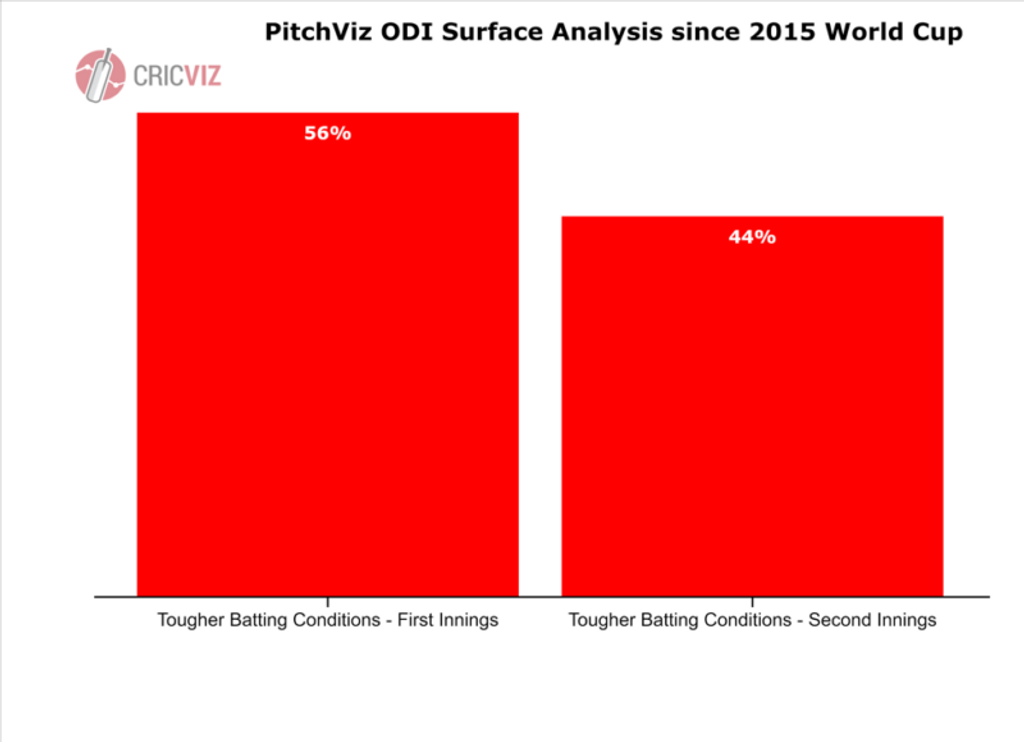

Over the last four years, ODI pitches have generally been weighted pretty fairly in this sense. Global surfaces have tended to be slightly easier to bat on in the chase, but only slightly. The skill of reading pitches, the ability of captains to predict how the surface will behave over the next 100 overs, is still necessary. Whether a pitch will get easier or harder to bat on is almost as evenly balanced as the coin toss itself.

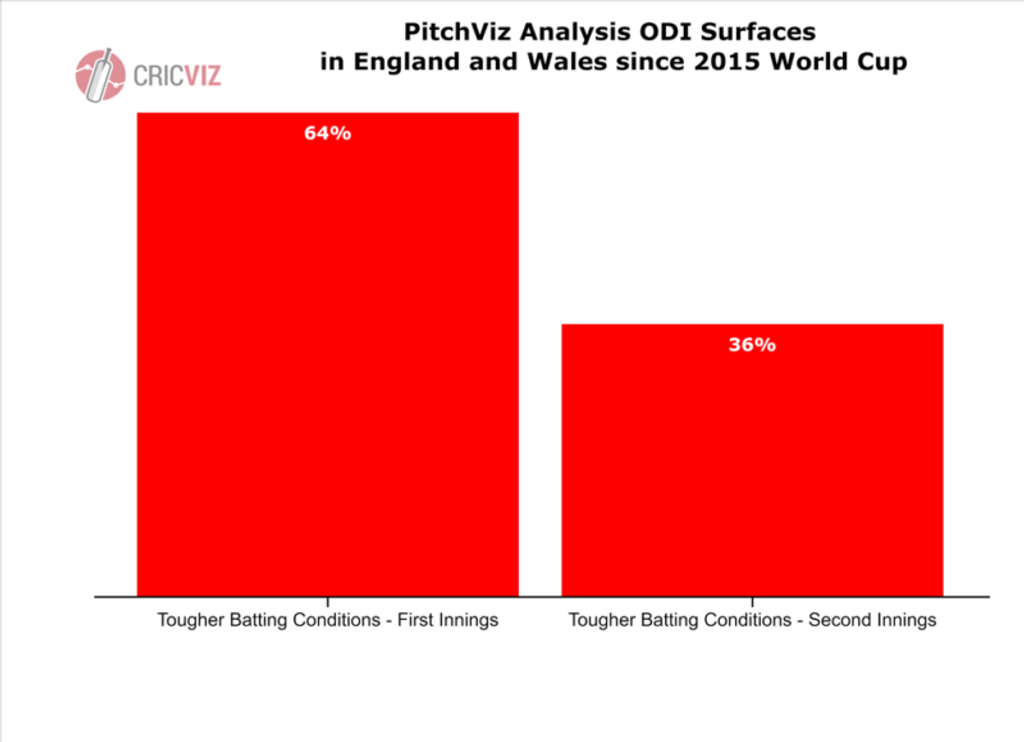

In England, it has been a bit different. Roughly two-thirds of the time, conditions have improved as the day has gone on. Eoin Morgan knows this; in the last World Cup cycle, England opted to bat first in a home ODI on just six occasions.

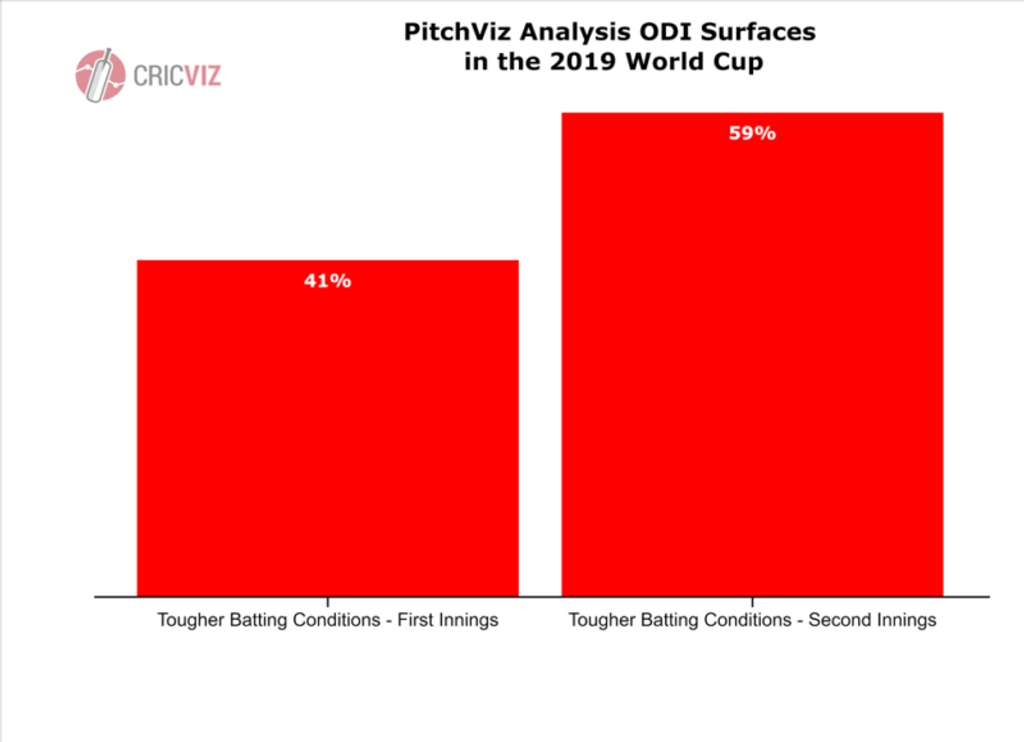

Yet in this World Cup, what we have come to expect about pitches has been turned on its head. More often than not, in this tournament the pitches have behaved like the one in Durham on Wednesday. They have been easier to bat on in the first innings of the match.

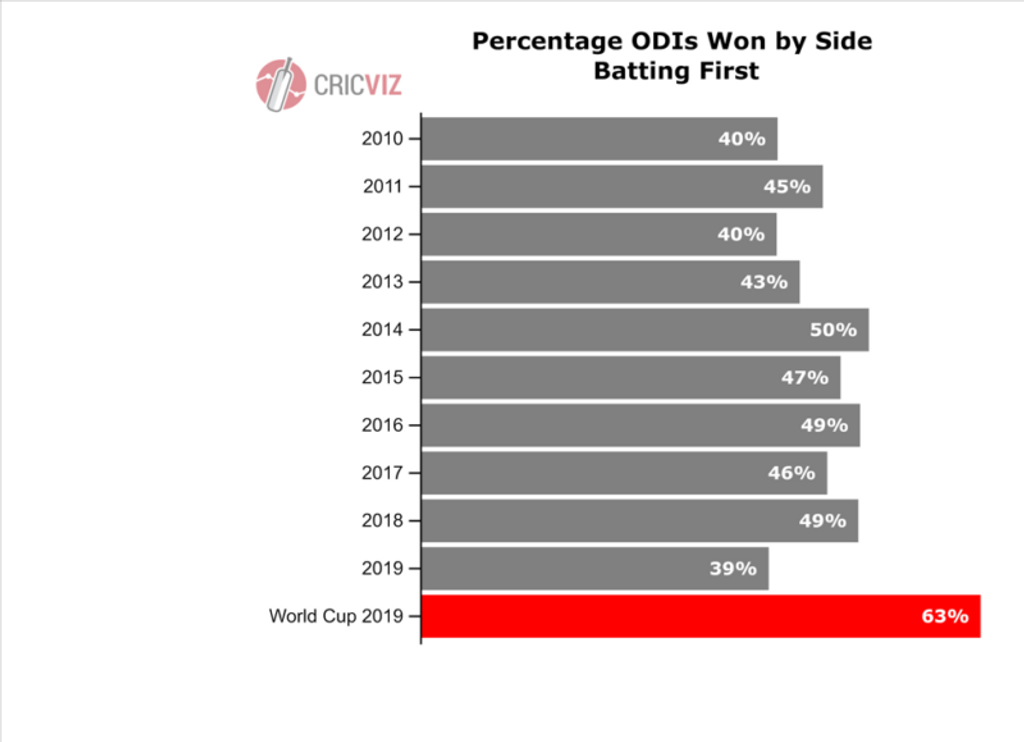

This could explain the unusually high success-rate for the side batting first in this World Cup. In the last decade, there’s never been a year where more than 50 per cent of games were won by the side batting first, but in this tournament 63 per cent of games have been. It stands out, as shown below.

This could be down to lots of things, from the intangibles of “World Cup pressure” to the practicalities of teams bailing on larger chases in order to preserve net run-rates – but it also looks like the actual 22 yards that the games are being played on are influential. Sides batting first are winning lots of matches because, well, conditions for batting first have been a bit easier. Who would have thought it?

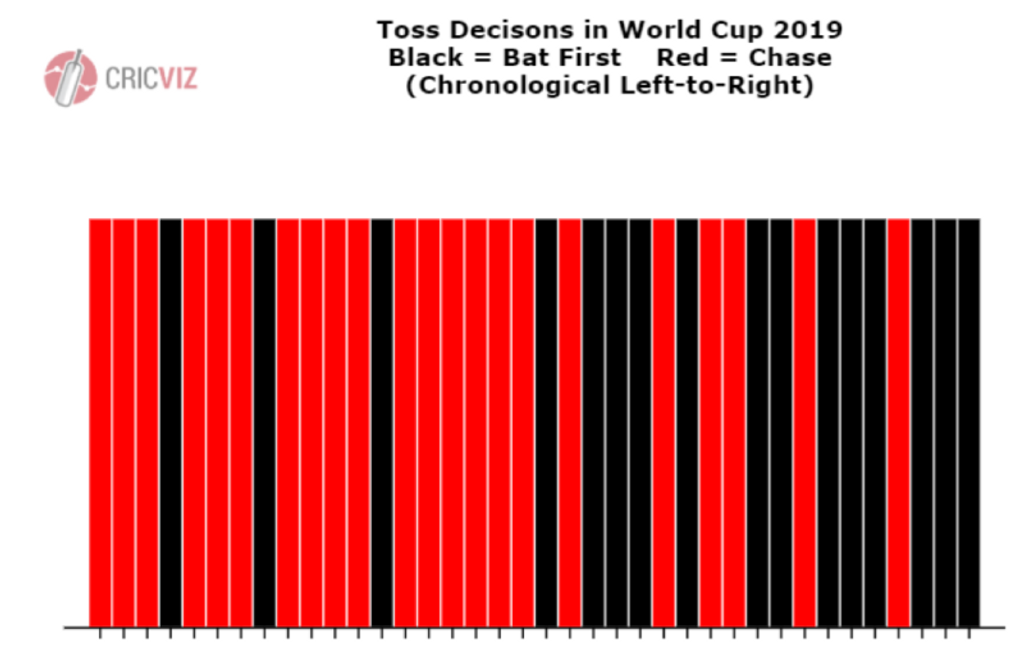

To be fair to captains, they have clocked this. Whilst plenty of elements are involved with deciding whether to bat first or to bowl first (opposition, weather, qualification requirements), the consensus that pitches have been slowing up is massive. Skippers have seen batting first as an ever more viable strategy as the tournament has progressed, and have increasingly opted to do so.

So basically, what we’ve seen in this World Cup is a fairly unique set of circumstances. Normally, pitches get easier to bat on, but in the last month or so, the opposite has been true. Normally, we’ve been seeing sides batting first lose the majority of the time, but in this tournament we’ve seen chasing sides flounder. Perhaps these two things are linked, perhaps not, but the important thing to take away from this is that pitches aren’t either flat or minefields.

We’re used to thinking about how surfaces degrade across a Test, but aside from general mutterings about dew in the subcontinent, we rarely afford ODI surfaces the same luxury – despite this evidence to the contrary. The pitches we play 50-over cricket on are as nuanced and changeable as their red ball colleagues, and should be afforded the same level of nuance when we’re discussing them. If we manage that, and improve the way we talk about pitches, we might find that our understanding of the teams and players that use them improve at the same time.

CRICKET WORLD CUP HOME