England’s win on a flat Rawalpindi pitch was not merely special: it may define how champion teams play cricket in the years to come, and go a long way in making Test cricket popular, writes Abhishek Mukherjee.

The finish was dramatic and the strokeplay dazzling, so much so that it is easy to miss the thinking behind England’s new strategy. But the tactics employed at Rawalpindi could be revolutionary. To see why, let’s go back to Test cricket’s first principles.

Barring the odd instance when teams declare and still lose, a side needs to take 20 wickets to win a Test match. That has not changed since time immemorial. As a logical conclusion of that, the superior bowling attacks have almost always won Test matches. Most exceptions to this – West Indies’s triumph over Australia in 1999 or India’s over Australia in 2000/01, to name two of the handful that exist – are almost invariably branded ‘miracle wins’.

Thus, it will not be an exaggeration to call bowlers the MVPs of Test cricket. Of course, they need the batters to make runs. In Test cricket, batters have often played for as long as possible, for runs are often directly proportional to balls faced. This held true, especially when great bowlers were fewer in number. One could see off their first spell and take advantage of the change bowlers.

However, there was a problem. While teams were not penalised for running out of overs with defeats, the stronger side often had to settle for a draws, because the bowlers would not have enough time to take 20 wickets. In other words, the slower the scoring, the more cautious the approach, the higher the probability of a draw. Thus, while batting for longer periods ensured more runs, they often came at a cost.

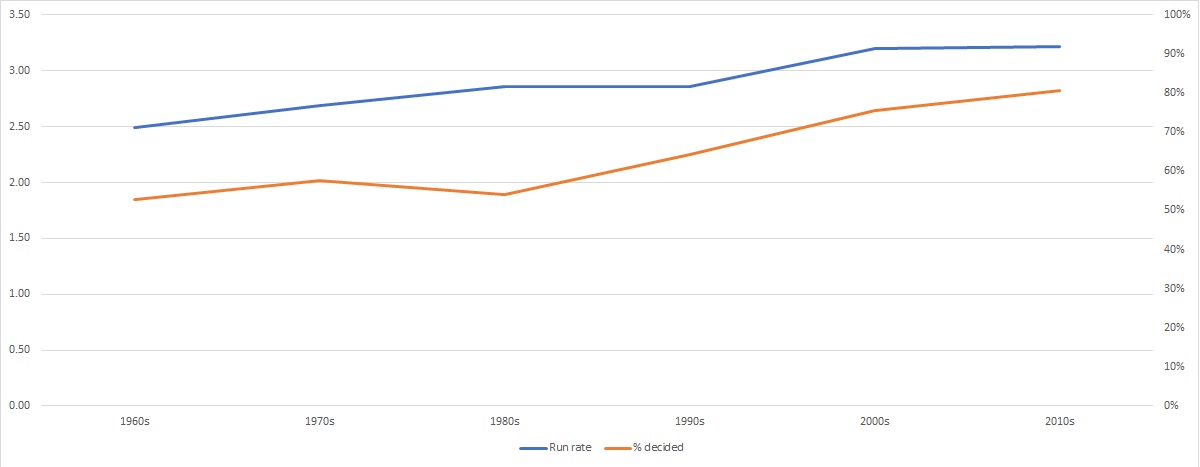

Plotting the run rate in Test cricket against the percentage of decided Test matches by decade may make the relationship clearer.

The 2010s, especially the second half, were not merely an outstanding era for fast bowling. As is evident from the graph, it also featured quicker scoring.

However, winning Test matches on flat wickets still seemed a problem. The Rawalpindi Cricket Stadium, venue of England’s first Test match on their Pakistan tour, had hosted Australia earlier this year. Only 14 wickets fell in that Test match, once every 27 overs (less than three a day). The hosts had lost four wickets in 239 overs of batting – a wicket every 60 overs.

What was more, bad light had reduced that Australia Test to 75.5 overs a day. In other words, the five-day match was likely to be reduced to four days and a bit.

Under these circumstances, England could have approached the Rawalpindi Test match in two ways. They could have accepted that it would be a draw, especially after their team had been hit by a stomach bug so pesky that it almost necessitated a delay in start of the Test match.

But that was not what England had in mind. They had come into the summer of 2022 with a solitary win in their last 17 Test matches. Now, with new coach Brendon McCullum at the helm, they decided to attack, particularly after they saw off the new ball. They won the first four Test matches, against New Zealand and India, and took the series against South Africa 2-1.

There was a pattern to their quick scoring. Across the first four Test matches, they scored at 4.01 in the first 10 overs (of both the first and second new balls) and 4.82 over the rest of the innings. They slowed down against South Africa, the run rates dropping to 3.23 and 4.02 – but they still scored significantly quicker after the ball got old than they did against the new ball. Bazball, some called the new method, after McCullum.

The obvious concerns were there. There was always a chance of a tactic working in the comfort of home venues but not elsewhere, certainly not in Asia. But while Asian conditions pose a challenge of a different sort, the new ball seldom poses as much threat as in England. The English batters could attack from ball one.

The benignness of the pitch and the bafflingly inexperienced Pakistan attack (they had fewer wickets between them than Joe Root by himself before the Test match began) allowed England to attack throughout the day without inhibition. They packed the XI with Twenty20 hitters like Liam Livingstone, Will Jacks, and Harry Brook, and set out to attack.

Much to the horror of traditionalists, record after record tumbled throughout the first day’s cricket. England attacked 64 percent of balls – the most in a day’s play since 2006 on the CricViz database – and roughly the same percentage of balls they have attacked in T20Is since 2015. They left only 13 balls alone. By amassing 506-4 on the first day, England put themselves in an position from where they would not lose unless something improbable happened.

England amassed 921 runs in 136.5 overs in the Test match – roughly four and a half sessions. That left their bowlers ten and a half sessions to take 20 wickets. Even if one deducted two and a half sessions for bad light, that came down to eight sessions, often enough time to take 20 wickets.

Since they adopted the new approach, England have managed to flip their 1-18 record into 6-1, but the Rawalpindi win was significantly more than an entry in that statistic. Given the odds – semi-fit cricketers, flat wicket, shortened days, unfamiliar conditions – picking up 20 wickets was unlikely unless they gave the bowlers enough time.

While discussing the bowlers, it must be noted that England’s attack, was not the best fit for the conditions. This was a pitch that demanded the stamina to bowl long spells. Since 2018, James Anderson had bowled 30.5 overs per match (not innings) away from home. Ben Stokes, 20.2 since 2015. Jack Leach had excellent numbers in both Sri Lanka and India, but this wicket was nothing like the surfaces he had played on. And Ollie Robinson had never played a Test match in Asia.

For this line-up to pick wickets on a dead wicket with the threat of bad light looming, the England batters could have adopted only one method if they wanted to win. They did exactly that. Their batting strategy did not merely make Test cricket attractive: it has also earned them a win where anything else would have at best secured a draw.

It is a template likely to be followed by teams when 20 wickets are improbable.