India are exceptionally difficult to beat at home. Since England’s 2012/13 series victory, India have lost just two Test matches on home soil – against Australia at Pune in 2017, and at Chennai again England in 2021.

At Pune, Steve Smith produced arguably his greatest Test innings and Steve O’Keefe played the game of his life; at Chennai, Joe Root scored a double hundred and James Anderson ripped the heart out of the India run chase on the final day. To win a Test in India – let alone a series – you have to be at the very top of your game.

Australia were not close to the top of their game on the first day of the series at Nagpur. The pre-match build-up was dominated by what were ultimately unfounded fears around how the Nagpur pitch would behave. Photos of the strip taken hundreds of yards away from the middle two days out of the Test were hyper-analysed, leading to accusations of ‘pitch doctoring’ from sections of the Australian media.

It’s hard to escape the conclusion that the noise around the pitch filtered through to the Australia dressing room and clouded their judgement at some level. The most glaring example of that muddled thinking was the omission of Travis Head, the No. 4 ranked batter in the Test game.

Head has a poor record in Asia but there is a there is a tendency to lump the conditions across all Asian countries together, when in reality surfaces can have marked differences in how they place; batting in Pakistan is very different to batting in India. Head has only played two Tests in conditions anything like what Australia encountered at Nagpur. When Head failed in Sri Lanka last year, he scored slowly and was easily bogged down – there was little chance of him taking a similar approach this time around. Since his last tour of Asia, Head has embraced his natural punchy, counter-attacking instincts. His 92 in the two-day Test against South Africa at the Gabba was arguably the innings of the Australian summer, during which he averaged 87.50 and struck at 95.10.

Peter Handscomb and Matt Renshaw were preferred in the middle order. Both are regarded as accomplished players of spin; Handscomb has the numbers to back up that claim; Renshaw – a left-hander like Head – not so much. Following his first-ball duck, Renshaw now averages 23.69 from seven Tests in India and Bangladesh.

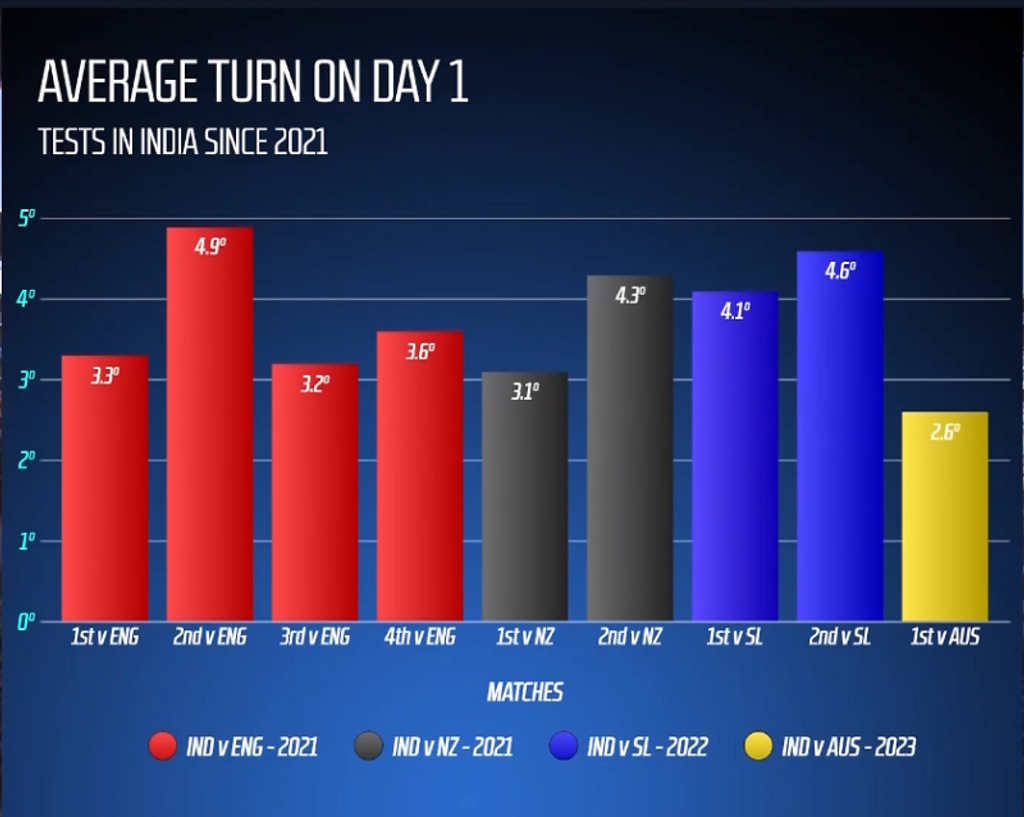

As it happened, it was pace not spin that first gave Australia cause for concern. David Warner and Usman Khawaja were both back in the dressing room by the end of the third over, falling to the pace of Mohammed Siraj and Mohammed Shami. Marnus Labuschagne and Steve Smith resisted for the best part of a session before Ravindra Jadeja and Ravichandran Ashwin combined to take the remaining eight Australia wickets. A graphic shown on the broadcast coverage showed that there had been less spin at Nagpur than on the opening days of the previous eight Tests in India – a stretch that includes England’s Chennai win.

The Head omission wasn’t the only example of Australia potentially letting their interpretation of conditions overly dictate their decision-making. Scott Boland was given just one over with the new ball before being hauled off for the off-spin of Nathan Lyon, just five hours after India’s new-ball pair had reduced Australia to 2-2.

[breakout id=”0″][/breakout]

Pat Cummins abandoned his typical back-of-a-length zone in a concerted effort to attack the stumps, bowling fuller and straighter than usual and was duly punished by an imperious Rohit Sharma who tucked into the gifts his opposite number was offering up. Cummins conceded 27 from his first three overs; a sixth of India’s deficit struck off in an instant. In a low-scoring contest, such passages of play are lethal. His three-over burst did as much damage to Australia’s chances as Warner and Khawaja’s combined failure.

The selection of Todd Murphy has at least paid off so far. He bowled with control and used the natural deviation on offer to threaten both edges from around the wicket. Murphy deservedly picked up his maiden Test wicket with a sharp off-break to KL Rahul in the dying embers of the day.

There were shades of pre-McCullum England in Australia’s first-day approach. At Adelaide in 2021, England picked four similar right-arm quicks for the day-night Test, leaving a red hot Mark Wood on the sidelines in anticipation of conditions that, in theory at least, would assist the more conventional English seamers. They overthought conditions and were a weaker side for it.

There are vulnerabilities in this India side, particularly their batting line-up. KL Rahul averages 17.44 since the start of 2022, Cheteshwar Pujara has scored one Test hundred in the last four years, Virat Kohli averages 26.20 over the last three years and there are two debutants inked in to bat at five and six. But if India are to be seriously threatened on home soil, Australia need to give themselves the best possible chance of success, something they didn’t do on the first day of Nagpur.