Ravindra Jadeja’s rise over the past few years has catapulted him into the pantheon of Test cricket’s greatest all-rounders, writes Abhishek Mukherjee.

Two thousand Test runs are not uncommon among Test cricketers. Of the 329 (about 10.6 of all Test cricketers) to have reached the milestone, 234 average in excess of 35.

Two hundred wickets are not as common. Only 81 bowlers (nearly a quarter of the 2,000-run count) have achieved the feat till date. Of them, 63 average below 30. An assortment of great bowlers but not necessarily legendary.

The fun begins when we combine the criterion – runs, wickets, and the two averages. The count drastically drops to two. One of them is Imran Khan – a man hailed by many as the greatest all-rounder in the history of men’s Test cricket.

The other is Ravindra Jadeja.

Of course, the criterion is slightly arbitrary. For example, Jadeja has 2,593 runs and 249 wickets, and will miss out if the bar is raised to 3,000 runs or 250 wickets. He has been brilliant, but not over a long enough span (his 61 Tests are the fewest in the 2,000 run-200 wicket clan).

Where, then, does Jadeja stand in this elite group of Test all-rounders?

Jadeja’s place in history

Jadeja’s primary strength is bowling, and in that department, his bowling average of 24.34 is the 22nd-best in history with a 200-wicket cut-off; the fourth-best among spinners, who traditionally have a higher average than seamers; and the best among left-arm spinners.

In that 2,000 run-200 wicket group, Jadeja’s bowling average is the sixth-best. Of spinners, only R Ashwin (24.05) has been better.

These are outstanding numbers by any standards – and that is without the secondary suit. Rank the same group by batting average, and Jadeja (37.04) rises, to fifth place, for this is a set of bowling all-rounders.

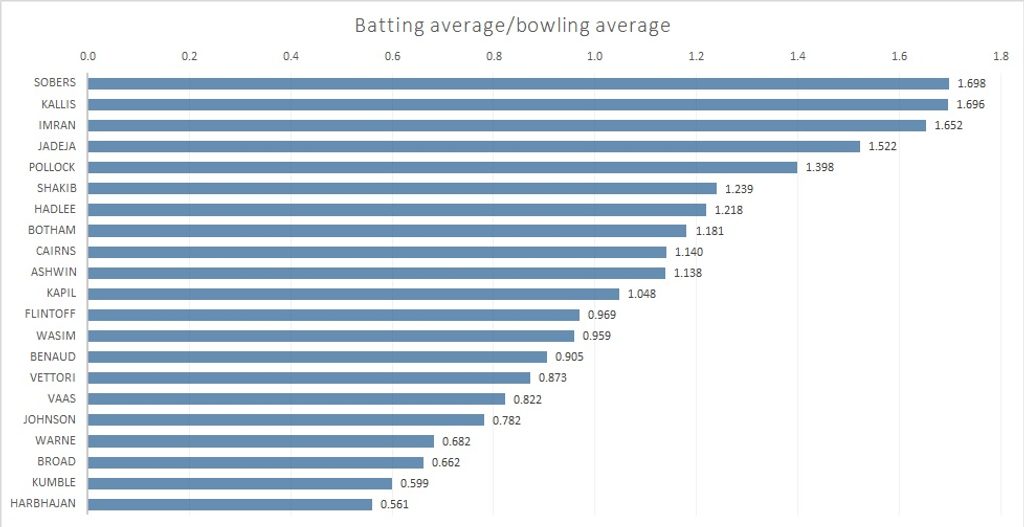

In terms of ratio between batting and bowling averages, Jadeja ranks the fourth best in history. The measure, while by no means perfect, is era-proof, as it takes into account both averages. It is also less skewed towards batting all-rounders like Garry Sobers and Jacques Kallis than the difference between the two averages.

How good is Jadeja the batter? He averages 44.16 with the bat since the start of 2016, a fantastic number in a bowler-dominated era. With a 2,000-run cut-off, only 11 batters have averaged more over this period. Of them, Joe Root has the most wickets.

Among Indians with 2,000 runs over this period, Jadeja’s average is next to only Virat Kohli’s and Rohit Sharma’s. There is little doubt that Jadeja could have played for India as a batter alone even if he did not bowl.

His batting has, at times, enabled India to go in with four specialist fast bowlers. Despite Ashwin’s slightly superior bowling average, Jadeja’s batting – he is a left-hander to boot – has allowed him an edge over the past few years.

Had he been a specialist bat with no bowling to worry about, he would almost certainly have done better at it – perhaps even played as a specialist. But then, he has also been India’s second-highest wicket-taker over this period.

Had his career not coincided with Ashwin’s – they are both fortunate and unfortunate in this regard, for at times one has played at the cost of the other – Jadeja might have been closer to at least one of 3,000 runs and 300 wickets by now.

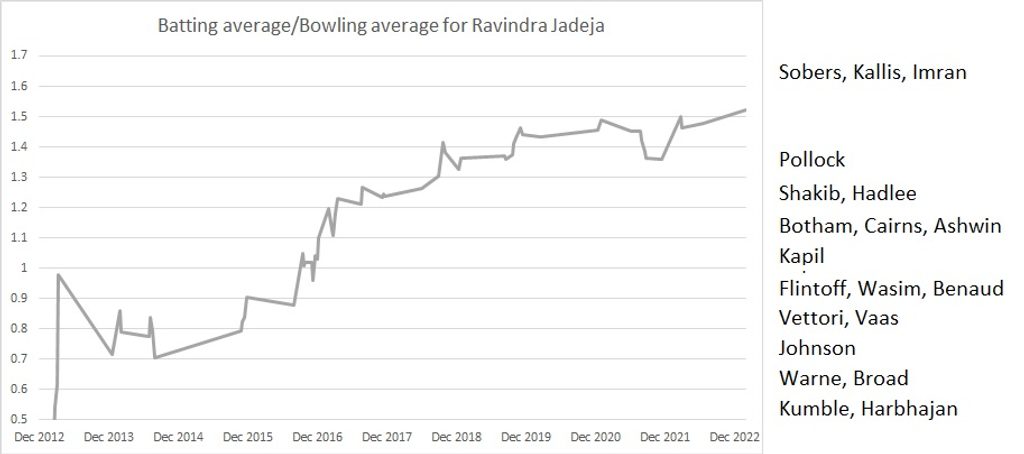

When one of them plays, it is inevitably because the conditions are not conducive for spin bowling. With the focus on the fast bowlers, Jadeja kept performing with the bat without compromising on the bowling numbers. As a result, the ratio between his two averages has gone up steadily over time.

He breached the barrier of 1.5 for the first time after his numbers got a substantial boost (175 not out to go with his nine wickets) during last year’s Mohali Test match against Sri Lanka. Following a tiny drop, he now has a career-best ratio of 1.522.

At the end of their respective careers, only Sobers, Kallis, and Imran have had a better ratio. And after 61 matches – the length of Jadeja’s Test career – Imran’s ratio stood at 1.47 and Kallis’ at 1.581 (though at 1.830 in the second half of the 1960s, Sobers had been enjoying his golden run).

At this point of his career, in 2002/03, Kallis’ batting average had been flirting with the 50-mark. It would soar to 55.37 over the next decade and a bit, just like Imran’s 31.86 in 1986/87 would scale the heights of 37.69 over the next six years.

A similar boost would take Jadeja past the 40-mark, perhaps somewhere around 43. If he does that without compromising on bowling, he may end up with the highest ratio of all time.