CricViz analyst Ben Jones on the ongoing struggles of England opener Zak Crawley.

The Ben Stokes and Brendon McCullum era has started emphatically. A series win against the World Test Championship winners, both victories coming in variously frenetic and improbable ways, has revitalised the feeling around England’s red-ball side. Be it the historic century from Jonny Bairstow at Trent Bridge, the success of Ollie Pope in his new role at No.3, or even the excellent debut of Matthew Potts at Lord’s, there is an unmistakable feel-good factor around this England team.

One of the few exceptions to that is Zak Crawley. The opening batter has had a lean start to his Test summer, with scores of 43, 9, 4 and 0, and his returns in the County Championship have been similarly underwhelming, averaging a sniff over 30. As the rest of the England team has been bounding along in a jubilant summer fling with their new beau, the Kent opener feels like a slight hangover from a previous relationship.

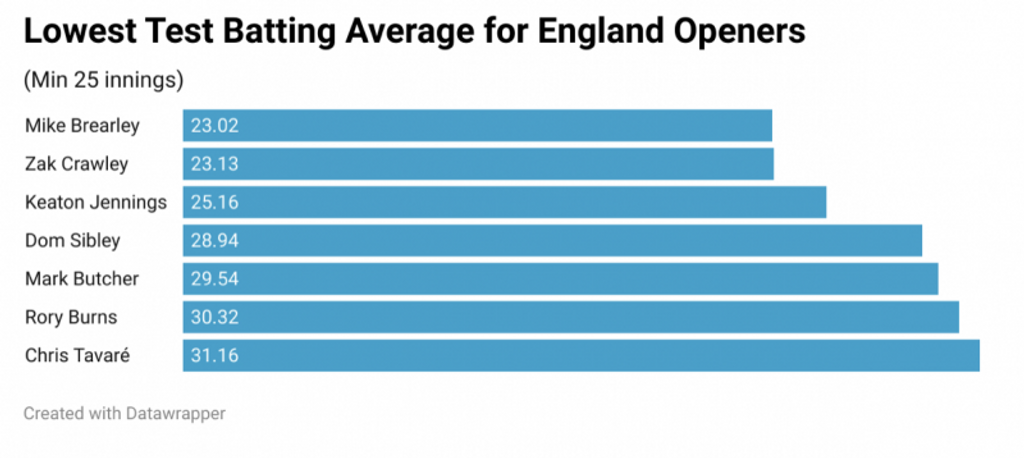

Historically, his record compares terribly with other established English openers. Of all men to open the batting for England as many times as Crawley has in Test cricket, only Mike Brearley averages less. Creative accounting from yours truly, given that magnificent 267 came when batting at No.3, but in terms of the role he’s being picked to do right now, Crawley’s record is abysmal.

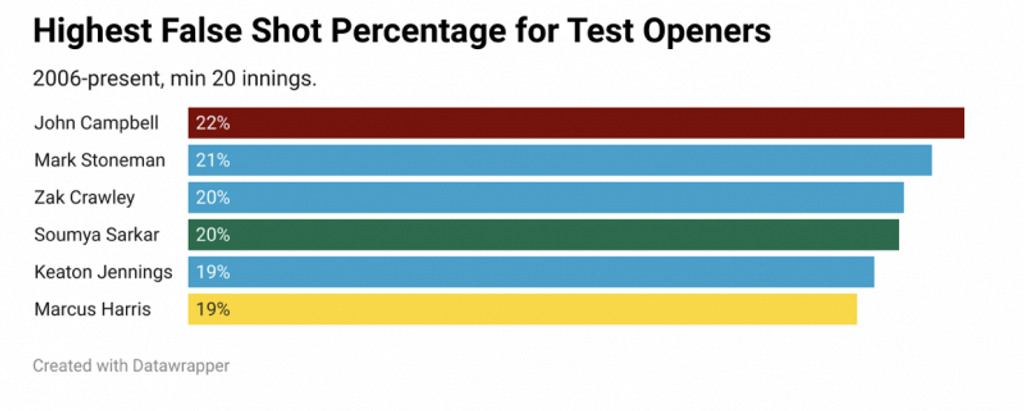

Quite simply there is a looseness to Crawley’s game that feels unsustainable without significant changes to his technique or approach. As an opener, Crawley plays a false shot to 20 per cent of the balls bowled to him; since this data was first recorded (2006 onwards), only two openers have been less secure in their strokeplay. One, Mark Stoneman, has already been dispatched by England (albeit with a superior average to Crawley), and the other has one of the worst records for an established opener in the history of the game.

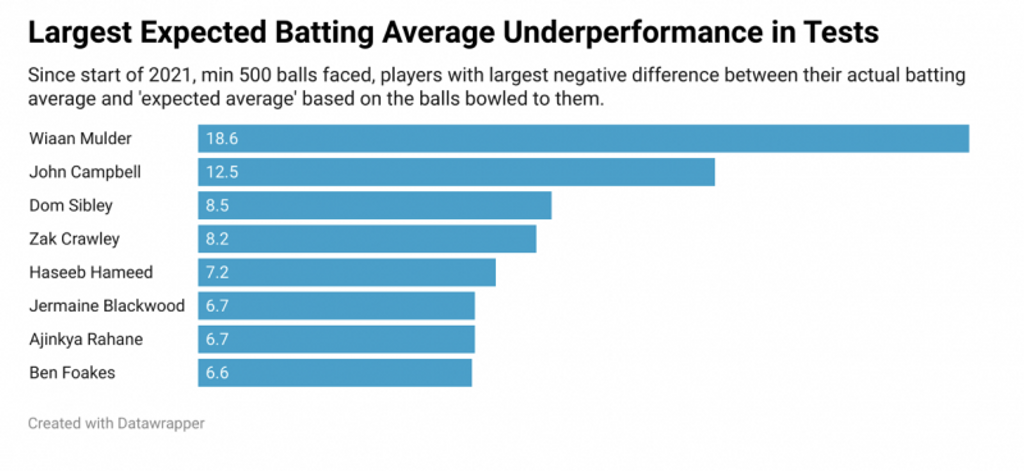

In the case of the Trent Bridge Test, Crawley did get out to two good balls. That can happen. The issue for him is that, more than almost anyone in the world, opening batters in England will get good balls, and Crawley’s specific ability to keep those good balls out is wildly unknown. Indeed, even when we factor in the difficult scenarios Crawley has faced in Test cricket, he still significantly underperforms. It is mealy-mouthed to state that the 267 came on a surface that PitchViz rates as the third flattest in England over the last 15 years, but it is not irrelevant.

In English cricket James Vince is often held up as the peak example of style over substance, of aesthetic appeal not translating into the cold hard currency of runs on the scorecard. Yet Vince averages more than 40 for Hampshire and is perhaps perversely held to a higher standard than others because of how good he is to watch. Crawley is arguably better to watch than Vince ever was, with a wider range of strokes and the beneficiary of a few inches in height and reach, but his record doesn’t come close, averaging just over 30 for Kent in first-class cricket.

This poor first-class record was easily and readily explained away when Crawley first came into the set-up. You heard a lot about how Crawley’s game was naturally suited to Test cricket, about how his back-foot focused approach allied with an intangible element of class to form a player who would thrive in the high-pace, high-quality environment of Test cricket. So far, that has not been the case.

However, for all this, Crawley has an almost ideological buffer to deselection. No, this isn’t a reference to the privilege and opportunity afforded by his wealthy upbringing, or the (undoubtedly overblown) patronage of Rob Key, but an acknowledgement the Crawley’s natural aggression and confidence fits squarely with at least a simplified version of Brendon McCullum’s ‘style’, the attacking mindset we saw in full glory on final day at Trent Bridge. Trevor Bayliss was often maligned for saying he wanted two strokemakers in the top three; you’d imagine McCullum would see that as one too few.

However, there is a cautionary tale for Crawley, walking alongside him as he heads out to bat in Leeds next week. The transformation of Alex Lees from blocker in the Caribbean to free-scoring playboy at work in Nottingham, is clear for all to see. While Lees was always more than the stodge and resistance that made a slow start to his Test career – Jason Gillespie would often refer to him as “Haydos” while both were at Yorkshire – here is a clear example of a player of fairly orthodox tempo stepping up and being encouraged to play at McCullum’s pace. Over the course of a few short weeks, England’s new set-up have shown they can make attacking openers out of orthodox ones. In that light, Crawley’s appeal dwindles.

Were he to fail in Leeds, and again in Birmingham against India, then there are a few rounds of Championship cricket for a contender to stake a claim prior to the South Africa series. Recent occupants like Rory Burns and Dom Sibley may need to mount a firmer case, but were any of the fresher faces to bang the door down with two, three centuries in that time, then the temptation to change things up may well be too great. Yet even with all of these illustrations of how much Crawley has struggled in Test cricket, continuity feels most likely. There is, ultimately, a collective willingness, from all but the most partisan proponents of their own county’s stars, to make Crawley work.

The numbers say it is highly unlikely that Zak Crawley will ever be a successful Test opener. If England want to take the logical, ‘correct’ step for the good of their side, then Crawley would not be in their best XI. Yet there seems a willingness within this Stokes-McCullum setup to resist logic. They seem content rolling the dice and backing talent over record, eyes fixed on an optimistic future rather than an inconvenient past. It’s a seductive mindset, boosted by these early results – and perhaps it’s the mindset which Crawley needs in order to deliver on the potential which so many see in his game.