CricViz analyst Ben Jones takes stock of England’s decision to promote Ollie Pope to No.3, a position he has never previously occupied in first-class cricket.

Ollie Pope is the most talented young batter in England and Wales. It’s become a throwaway line, a preface to criticism, but it’s worth sitting with for a second. Pope is a 24-year-old who averages 69.34 in the County Championship. He is an enormous talent and managing the progress of this player, and his journey from prospect to elite batter, is the most pressing project England’s Test hierarchy has on its plate.

What’s more, there is no question that this progress has stalled. After his century against South Africa at the start of 2020, Pope averaged 51.85 in Test cricket. Even at the end of that Test summer, his average was still an encouraging 37.94. It felt right: a young player who many had identified as the best of his generation, delivering qualified early success as he began his career at the top level. Since the end of that summer, Pope’s averaged 20.36 in Test cricket.

And so the timing of Rob Key’s announcement that Pope would be moving to No.3 for the Test series against New Zealand caught many on the hop. This is not a youngster hammering the door down, unequivocally ready for the step up. England’s new No.3 batter has never batted there in a first-class match; that may not prove to be any sort of problem, no hindrance to his future success, but it isn’t good.

It’s important that counties retain a good degree of tactical autonomy, for the integrity of the competition, but it’s also counter-intuitive for the ECB to not direct certain players into certain roles in order to groove their skills for international performances. In the case of Ollie Pope, nobody saw fit to direct him to first drop, and while in the last few months that was largely because nobody was in post to do so, in the last few years the main explanation is probably quite simple – nobody saw Pope as a No.3.

That is probably for good reason. The first thing you would say is that Pope is unusually attacking for a No.3 batter. In recent years, he averages 27 per cent attacking shots in Tests, significantly above the overall average of 21 per cent that we see for other Test No.3s. He does not leave the ball very often, only 16 per cent of the time against pace, with other No.3s averaging over 25 per cent. This is obviously a product of batting down the order and often being tasked with counter-attacking, but Pope’s natural game is clearly to be aggressive. There’s a sharp contrast with when Joe Root was making his way in the Test team as a youthful No.6, his scoring rate only just rising above 2rpo shortly before being promoted to open the batting. Pope, for all his quality and potential, has rarely batted with the tempo you’d associate with a No.3.

Of course, people can over-emphasise how unique No.3 is as a position. In conversation with the Evening Standard, Pope referenced how Hashim Amla had told him “it’s one ball different from No.4”. It’s a good line, and the spirit is clear, but it’s also not really true – it’s more like 60 balls away. On average, a Test No.3 faces their first ball in the 11th over; a Test No.4 faces their first ball in the 22nd. The knock-on of that isn’t rocket science – No.3 is simply a harder position to bat than No.6. In the last decade, the Expected Average of deliveries bowled to a No.3 batter in England is 28.3; for a No.6, that figure is 31.1. It’s only a slim difference, over a significant sample, but it’s a difference nonetheless.

So, aside from the universal belief in his talent, what is the state of Pope’s game in Test cricket right now? Pope’s game against pace has evolved over the last few years, but there are clear patterns across his career. Like many batters, Pope’s main issues have been against classical good length deliveries, pitching between 6m and 8m from the batter’s stumps. Facing these deliveries, he averages just 18 runs per wicket, comparing poorly with Root (34), Stokes (26), and Buttler (27), but favourably with other recent No.3 incumbents Zak Crawley (16) and Dawid Malan (12). In other words, it’s an understandable weakness, to an understandable level.

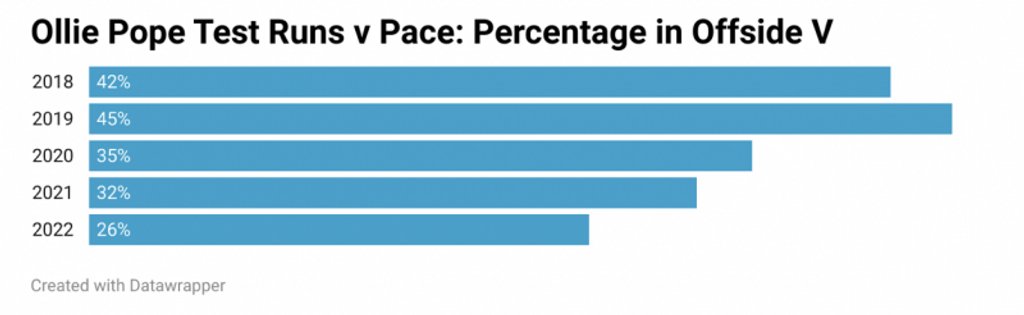

However, there have been significant changes to Pope’s technique over the last few years, which emphasise some more specific, more concerning issues. For all the Ian Bell comparisons, Pope’s early dominance at Surrey, as well as his initial forays into Test cricket, were defined by a devastating cut shot rather than an elegant drive, and he was incredibly offside dominant against seamers. In those early years, basically half of his runs came through point. Setting up so you could see plenty of the stumps, Pope would lace the ball square consistently, cutting deliveries that plenty of others would hit far straighter.

The transformation in Pope’s style of play is extreme. The current incarnation of Pope, less than a third of his runs come through that point region. While screenshot analysis is a dangerous game, even a brief glance at how Pope sets up at the crease can suggest why this is. As you can see from these two images of Pope batting – on the left against India in 2018, on the right against South Africa in 2020 – he has moved across his stumps, towards the offside. From here, far fewer deliveries are wide enough to cut, and so his copious scoring through point has diminished.

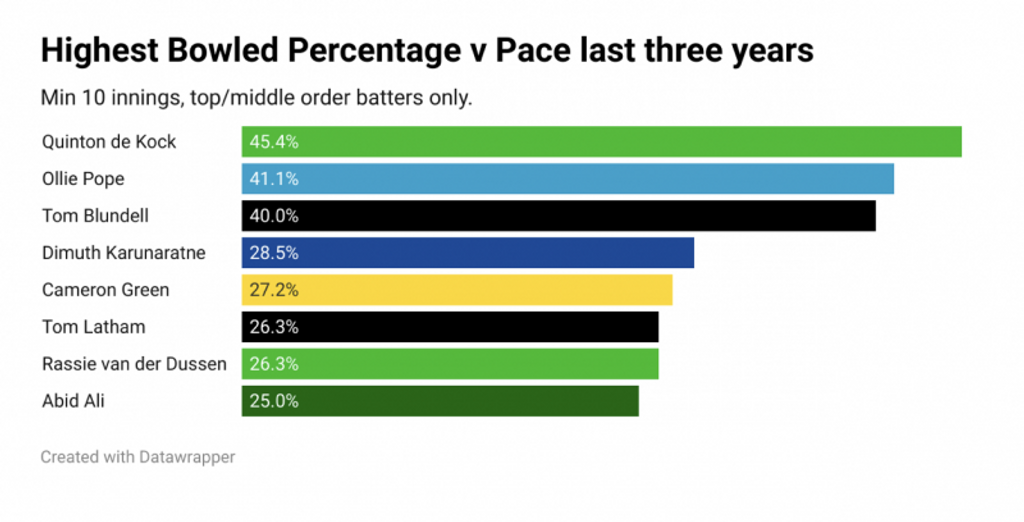

The other apparent consequence of this move across the stumps is that while Pope now rarely nicks off, he is far more vulnerable to being bowled. In his first 10 Test matches, Pope averaged a very impressive 43 against balls on his stumps from seamers, but since then – and since this move away from that initial setup – his average against those balls has dropped to just 16. Indeed, going back to the start of 2020, only one top-order player has a higher bowled percentage against pace than Pope.

Add to that the fact that all but one of those dismissals has been a delivery moving back in off the seam, and it’s clear that the major block to his progression as a Test batter has been getting bowled by nip-backers. Again, as weaknesses go it’s far from fatal – those are very good deliveries – but the repetitive nature of these dismissals does suggest this is a technical ‘fault’.

Data analysts are not batting coaches, and shouldn’t pretend to be. Pope, and those around him, are more aware of the strengths and flaws in his game than anyone else. There is no right way to bat. What we can say though, is that one technical change has significantly reduced one strength in Pope’s game, and exaggerated (or perhaps even created) a now profound weakness against deliveries coming back into him. If he is to succeed in Test cricket, and certainly if he’s to succeed to the degree many believe he could, he will need to eliminate this weakness.

However, there is an argument that Pope is as likely to eliminate that weakness at the top of the order as in the middle. While No.3 is harder than No.6 in terms of the quality you face, in terms of the deliveries you face in UK Tests, it’s not particularly different. At every stage of the innings, in every position, around five per cent of the deliveries you face are nip-backers on the stumps. Clearly there are other challenges which come with facing fresher bowlers, being afforded less rest after fielding, and myriad others, but in terms of Pope’s particular weakness, the challenge doesn’t change.

Ultimately, for all its grandeur, Test cricket is not enormously tactical. There are fewer moving parts, more room for error and failure. It is primarily a technical and, by virtue of its length rather than any superior moral standing, a mental contest. In white-ball cricket, incorrect deployment of a batter can be an insurmountable burden for the player involved, setting them up to fail; there are examples of that phenomenon in red-ball cricket, but they are far rarer. Test cricket is a far more individual form of the sport, and the responsibility for success falls more squarely on the players.

English cricket often has a tendency to overthink, to over-intellectualise and lose sight of the basics. In many cases this brings significant rewards, most notably in white-ball cricket, but it can also block off options. The Pope to No.3 argument is a nice example of this dynamic. There are plenty of substantive, well-informed reasons for why Pope will not work at No.3 – some of them above – and for why his potential may be better nurtured down the order. But the counter is that cleaner, crisper logic which Key channelled in the press conference where Pope’s move was announced, focusing on the fact that this is England’s third best batter, and has the talent to make the move work. It’s a directness best performed in an Australian accent, invoking a less existentially earnest cricket culture, and one far more trusting of natural ability.

And maybe, that’s where we are with Ollie Pope. England tried throwing him in the deep end back in 2018. They tried nurturing him down the order. Both worked a bit but were broadly unsuccessful. The sensible, logical option is to continue with him down the order; the bold option is to back him, trust him, and see what he can do. But if it backfires, it should be those throwing him in the deep end that take the criticism – not the boy who drowns.