The Player of the Match award in ODIs is unfairly skewed towards batters, and that is something that needs to change, writes Abhishek Mukherjee.

To bet on the World Cup with our Match Centre Partners bet365 head here.

Aided by a belter of a surface and the humble dimensions of the Delhi ground, South Africa broke nearly every conceivable World Cup record during their innings of 428-5. Sri Lanka then responded with 326. In the entire match, no bowler went for under a run a ball.

In the second match at the same venue, Mohammed Siraj, Hardik Pandya, and Shardul Thakur – three of the four India fast bowlers – had combined figures of 22-0-150-3. Kuldeep Yadav and Ravindra Jadeja, the spinners, kept it to 78 in 18 overs, but struck only once between them.

Given the conditions, the target of 273 was never going to trouble India. Aided by Rohit Sharma’s delightfully violent 84-ball 131, India cantered to a win. Every Afghan bowler conceded more runs than balls bowled. The margins of victory – eight wickets, 15 overs – suggest that India would probably have won even without Rohit’s masterpiece.

There were several other innings of note in the match: Hashmatullah Shahidi (80) and Azmatullah Omarzai (62) added 121 for the fourth wicket; Ishan Kishan’s run-a-ball 47 went unnoticed as Rohit went on rampage; and Virat Kohli remained unbeaten on a quiet 55.

In conditions that offered him little, Jasprit Bumrah altered his length early in the innings, abandoning attempts to find swing in the air. His 4-39 did not come against an all-conquering opposition, but it was one of the finest displays of fast bowling on an unhelpful surface.

On a flat pitch, the adjudicators named Rohit, who played the best of several reasonably good innings, the Player of the Match ahead of Bumrah, who bowled the only spell worth a mention.

Unfortunately I couldn't watch Rohit's innings so maybe my assessment isn't entirely accurate but it must have been from another planet to trump Bumrah's bowling on that pitch for player of the match.

— Harsha Bhogle (@bhogleharsha) October 11, 2023

In India’s previous match, against Australia on a Chennai pitch that induced turn, the award had gone to KL Rahul for his unbeaten 97, not Ravindra Jadeja’s 3-28. It both instances, the batter got the award irrespective of whom the conditions aided.

In the first ten matches of this World Cup, eight awards have been given for batting performances and one (Mehidy Hasan Miraz) for an all-round display. Mitchell Santner had to become the first New Zealand spinner to take a World Cup five-for to convince the adjudicators to think otherwise (given the trend, they might well have gone for a batter, had Santner not blasted a 17-ball 36 not out).

This brings us to two questions. Do batters win Player of the Match awards more than bowlers in ODI cricket? If yes, why?

This tendency is both older and deeper than this World Cup alone. It spans the history of ODIs, the format that has had the Player of the Match awards since inception (Test cricket had series awards since the 1968 Ashes, but match awards were introduced only in 1975).

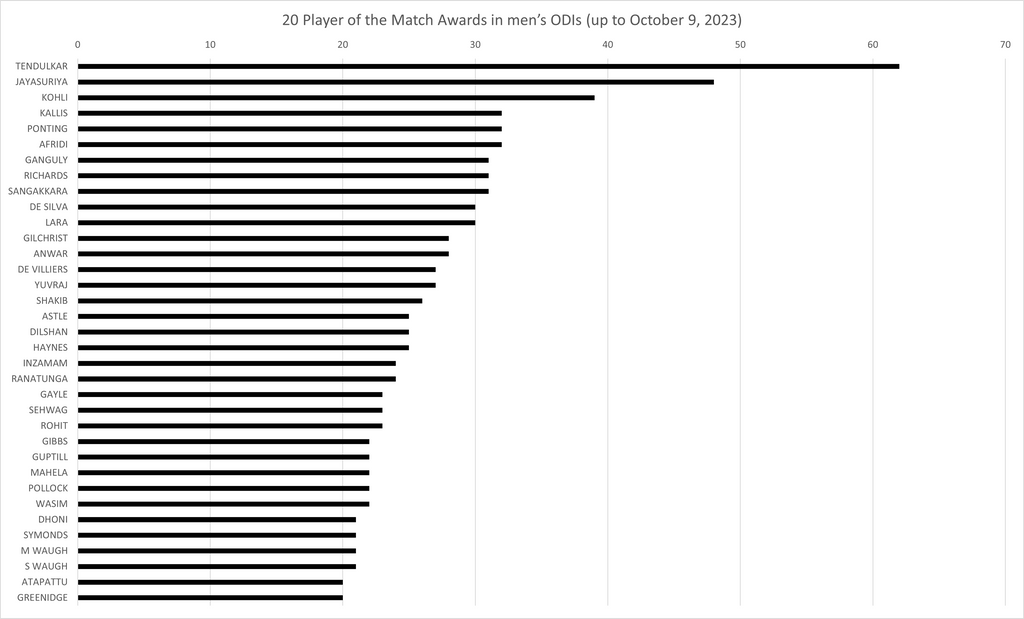

Put a cut-off of 30 awards, and only Sanath Jayasuriya, Shahid Afridi, and Jacques Kallis make it among all-rounders. Extend that to 25, and Shakib Al Hasan is the only addition. In ODIs, all four were – are – at least as good with the bat as they are with the ball.

Of cricketers primarily in the side for bowling, Wasim Akram tops the list, with 22. He is also the only entry – out of 35 – when one reduces the cut-off to 20 awards.

Of course, some of the remaining 30 have reasonable ODI bowling careers – Sachin Tendulkar, Sourav Ganguly, Viv Richards, Aravinda de Silva, Yuvraj Singh, Nathan Astle, Tillakaratne Dilshan, Andrew Symonds, the Waugh brothers.

While that is true, it is undeniable that batting was their stronger suit by some distance. The odd exception aside, their batting won them the awards.

This is not a small sample either. Between them, these 35 cricketers have been rewarded 960 times – 21.8 percent of all Player of the Match awards in the history of the format.

That brings us to the second question: why do adjudicators prefer batters?

The historical class divide – the elite, who ran the sport, were mostly specialist batters – is unlikely to be a reason, for that was no longer relevant as cricket evolved into the modern period. This is perhaps demonstrated by the fact that Muttiah Muralitharan, Shane Warne, and Wasim are all in the top four on the list of most Player of the Match awards among Test cricketers.

On the other hand, in men’s T20Is, no specialist bowler from ICC Full Members has won the award even seven times (Kohli leads the list with 15), though the all-rounders make their presence felt.

Perhaps it because specialist bowlers are restricted to 20 percent of a limited-overs innings, and rarely bat enough to alter the course of a match. Batters can theoretically face every ball and if they bat through the innings, they are roughly expected to face 50 percent of all deliveries available to the team. All-rounders find a place, for despite the restriction on their bowling quota, they have a second chance in the match.

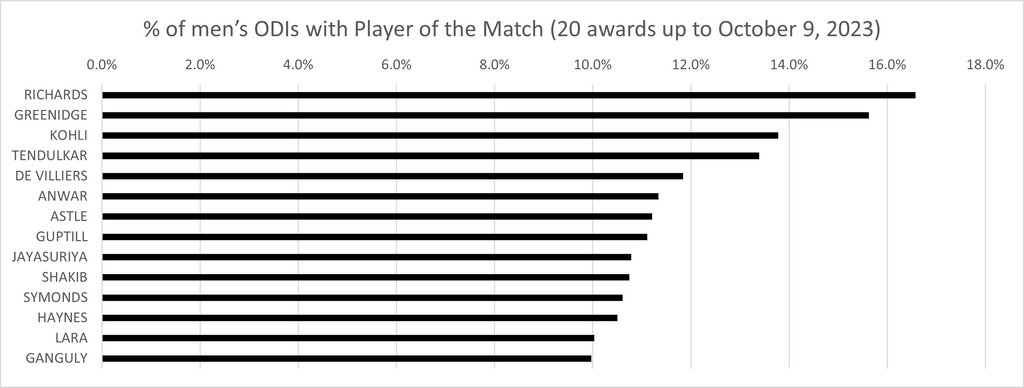

This is perhaps more evident if one looks at the most frequent winners of the 35 cricketers mentioned above.

Barring Shakib and Symonds, every cricketer to have won the award at least once every 10 ODIs has preferred to bat inside the top four. The more balls they face, the likelier they are to win the award.

The ODI Player of the Match obviously goes to outstanding cricketers, but of them, they perhaps go to the ones who make their presence felt for longer periods in the match.

Of course, it is not the bowlers’ fault that they are restricted to 10 overs per outing. Perhaps a scoring system will help eliminate the bias and make it a fairer ground.