The final acts of Stuart Broad and James Anderson on an Australian cricket field evoke the departures of another great double act, prompting Phil Walker to wonder what this bowling attack can possibly look like when they are gone for good.

There was a moment here, just before tea, at the fall of Australia’s second wicket – before the contest died with the advent of the unreal Steve Smith – that transported the whimsies among us back to late summer 2000; to a corner of south London, and the quiet departure of two literal giants of the game.

The wicket was David Warner’s. He’d played breezily up until then for fifty-odd, but had lost his fluency with the return of first Stuart Broad, and then James Anderson. In the event it was Anderson who finished what Broad had begun. A gripping off-cutter, delivered with a sudden, almost showboating click of the wrist, encouraging Warner’s prod to be taken low by Jonny Bairstow.

Anderson outwits Warner for his 522nd Test wicket

Anderson outwits Warner for his 522nd Test wicket

Initially, in his follow-through, Anderson gestures to the away fans at long leg, before teammates converge for the ensuing melee. Broad, meanwhile, fashionably late, has ambled in from mid-off. Anderson breaks away from the high-fives and the fluorescent drinks-carriers. Broad, who took a wicket in his first over with a belting inducker to remove Cameron Bancroft, is the last man left. They nod to one another, conspiratorially – to a plan that’s come together, to another theory borne fruit – and briefly embrace. There are no words needed or offered. They’ve all been said.

Broad and Anderson. Inextricably linked, as with all the greats of the fast-bowling game. Lindwall, Miller. Larwood, Voce. Truman, Statham. Lillee, Thomson. Wasim, Waqar. They are in there. No question.

They have now taken 922 wickets between them. Broad is one shy of 400, and should have got there this afternoon, when Smith edged a leg-cutter an inch short of Bairstow, just fine of first slip. (To be fair, the freak probably meant it.) Anderson meanwhile is playing his 134th Test, now the most by any fast bowler in the history of the game.

At the MCG last week he went past Courtney Walsh in the big list; of the quicks, only Glenn McGrath now remains, the Dubbo metronome firmly in his sights. And it was to Walsh that the mind wandered today – to Walsh and his mate, and another double act from the gods.

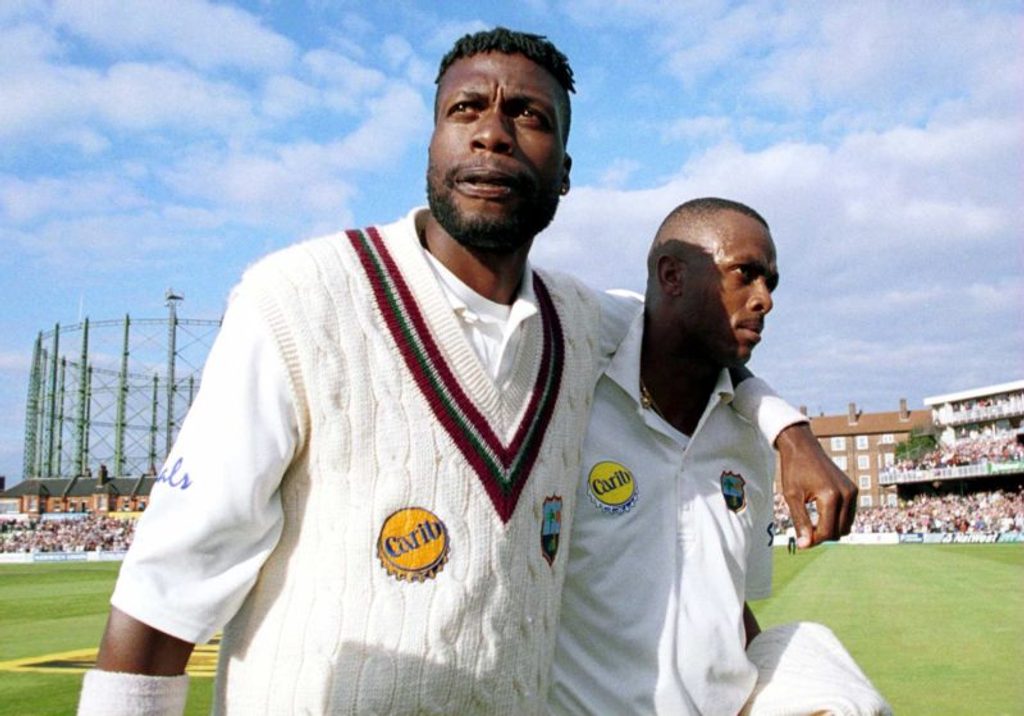

Curtly and Courtney depart the scene together for the final time; The Oval, 2000

Curtly and Courtney depart the scene together for the final time; The Oval, 2000

That image from The Oval in 2000 spoke of two quiet men, shattered beyond comprehension, traipsing off arm-in-arm one last time. Of comradeship and duty, and body-crushing longevity; of burdens shouldered over and above any reasonable measure, departing a famous old ground, defeated in the match and series but unbroken in themselves, knackered yet immense – and immensely knackered.

That summer, Courtney and Curtly had shared 51 wickets, at averages of 13 and 18 respectively, and still the West Indies lost. The support acts of Franklyn Rose, Nixon Mclean, Reon King, with 19 wickets across nine Tests combined, had seen to that.

With their departures (staggered by a few months but essentially there, that very day) went something of the spirit of West Indies cricket. The greatness-lineage simply stopped there. It was not some mere fluke of time, two great bowlers ducking out together, so much as a terminal decline that had been coming for years but which still jarred like hell when it came.

Perhaps it’s the heat, or the fag-end of a sapping tour, but watching Broad and Anderson at work today felt like an oddly poignant exercise. If such reflections feel a little premature with three days still to go, it’s by no means guaranteed that they will have a fourth innings to bowl in. This may well be their final stint in Australia. And they have, as ever, been stoic, clever and cranky throughout; and far and away the best seamers England possess.

Bancroft is beaten all-ends-up by a Broad inducker

Bancroft is beaten all-ends-up by a Broad inducker

Come what may, at the end of this match they will walk off an Australian cricket field for the final time. It is a sorry reflection of the lovelessness that exists between foreign players and modern cricket fans that the reception is unlikely to bear much resemblance to the one afforded to Ambrose and Walsh two decades ago.

The fear for England, of course, is what the picture looks like when they are gone. It is an indictment of England’s planning procedures that we are staggering towards the end of two titanic careers with no obvious succession process in place. We can cling to the notion that fast bowlers more than any other cricketing species tend to emerge from nowhere, unknowns in June, wrecking balls in July and spearheads in August, but that would be a flimsy hope.

Broad is disconsolate after Smith edges between the keeper and first slip

Broad is disconsolate after Smith edges between the keeper and first slip

Many have been tried and backed, for such inconclusive returns. Steven Finn was the great white hope, who took 14 wickets in three Tests here in 2010 and nothing out here since – his pre-series injury was unfortunate, but he had not been selected in the original 16; Mark Wood was the golden bullet they can never get on the park; Chris Woakes the hip-swinging Jimmy-apprentice who’s exposed when it’s flat; Jamie Overton bowls a heavy ball at a pace that will never offer more than a containing option; Tom Curran is skilful and game but pedestrian; Jake Ball was picked and quietly sidelined after the Brisbane Test, perhaps due to the Test average of 114; Toby Roland-Jones, who would have played out here but for injury, is already 29 and has played just four Tests… we could go on.

Of that list, Finn is the only one to have taken 100-plus Test wickets, but of his 125 wickets so far (at a decent average of 30 and a very good strike-rate), just five of them have come in the last 18 months. The fact is, the post-Branderson landscape is a shapeless mishmash of Pollockian spatters, and no one has the slightest idea what it’s going to look like.