On the back of an excellent IPL campaign with Chennai Super Kings, how can Sam Curran – selected for the T20Is against South Africa – boost a fit and firing England side? CricViz’s Ben Jones investigates.

It says something about the stability in the current England T20 side that the selection debates taking place are limited to the question of batting orders and backup options. The first choices are all but nailed, with Eoin Morgan’s preferred core of players seemingly not budging.

The only place where there appears to be wiggle room is the fourth/fifth bowler, and No.7 batsman. Moeen Ali has slipped out of form with the ball, and while the line of suitors is not long, there is quality for England to turn to. Sam Curran, fresh off the back of a 14-game IPL season, feels like the coming man. His side, Chennai Super Kings, may have endured their worst season in recent memory, but Curran was a rare source of optimism: 186 runs at 7.9rpo and 13 wickets at 8.2rpo represented a very strong all-round campaign for the England left-armer, and it has catapulted him into contention for international selection.

In some respects, Curran’s selection would represent something of a gamble. There aren’t many 22-year-olds firmly assured of a place in an international side, regardless of the format. England, in some respects, would be taking a punt on an unknown quantity – Curran has played five T20 internationals for England, a record which consists of just 23 balls faced and 108 balls bowled.

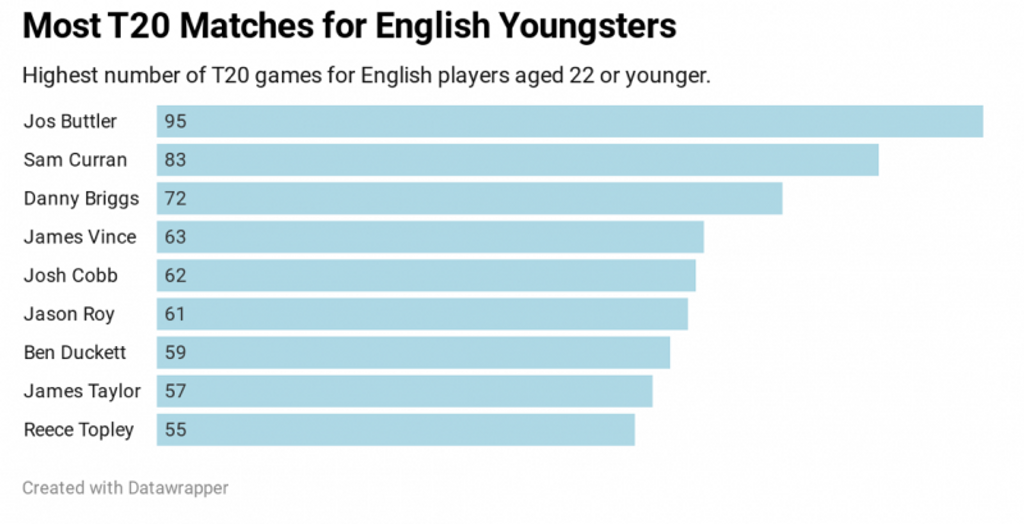

And yet Curran, a prodigy regardless of format, has accrued a wealth of T20 experience unmatched by almost everyone in English cricket. Still yet to turn 23 years old, he has played 83 T20 matches in total; the only English player to have played more T20s than Curran has at this age is Jos Buttler.

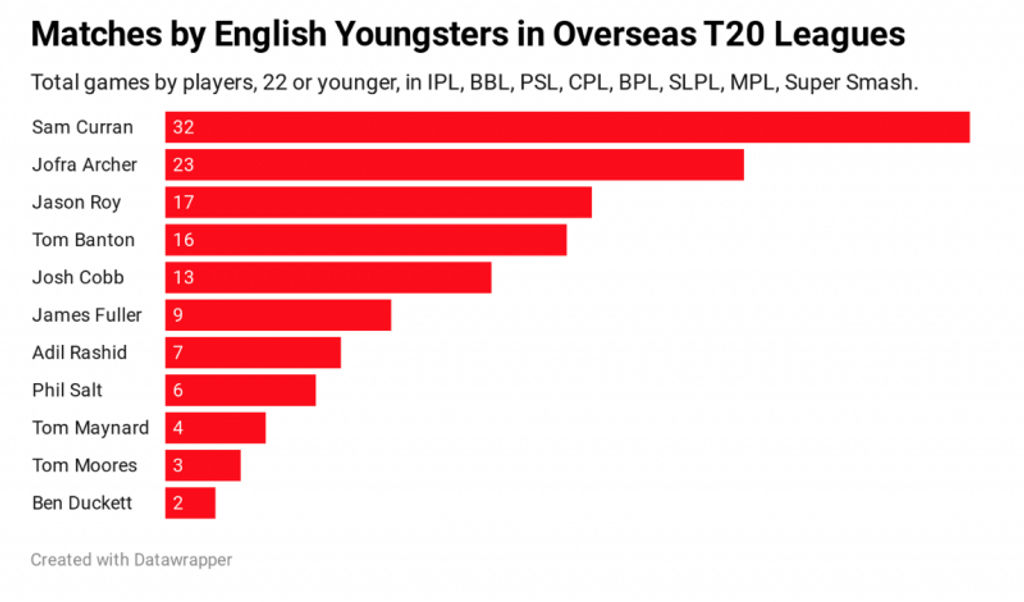

For Buttler, however, all of those appearances came for Somerset (65 matches), England (28) and England Lions (2). For Curran, his T20 development has been an altogether more global process, seeing him turn out for Chennai Super Kings (14 matches), Kings XI Punjab (9) and Auckland (9), as well as Surrey (46) and England (5). Almost half of Curran’s domestic T20 career has come outside of the T20 Blast; more than half of his last 40-odd matches have come in the IPL.

Indeed, Curran’s exposure to overseas T20 cricket at such an early stage in his career is greater than any other England youngster. Only three English players have ever played for multiple overseas T20 sides before their 23rd birthday: Tom Banton, Jofra Archer, and Curran himself.

Due to the limitations of Chennai’s squad this season – a surplus of right handers, in the absence of Suresh Raina at No.3 – Curran’s left-handedness made him a very useful weapon with the bat. In a tactical climate focused on matchups, the Englishman’s ability to come in and target leg-spin and slow left-arm bowling was a huge asset to Dhoni’s side.

Occasionally Chennai deployed him in the middle order, occasionally just before the death overs, and on three occasions, as an opener. Curran has now opened the batting four times in T20 cricket, all four of them in the IPL (once for Kings XI, three times for Chennai), and while he’s hardly set the world alight in this role (73 runs in four innings, at a scoring rate of just under 7.5rpo), it’s another tool in his belt.

Opening with Curran was not an experiment that Surrey have ever conducted (though he has batted at No.3), nor one England themselves need to. If England did find themselves with a side lacking in left-handers, as unlikely as that would be given Stokes, Malan and Morgan’s current status, then Curran’s IPL stint leaves England with a trick up their sleeve.

Debating how the Indian Premier League benefits England is no longer necessary. English cricket has come a long way from the turned up noses, the scoffing, the general sense of sceptical distaste which pervaded all discussions of the Indian Premier League. Administrators who pushed back against it now embrace it. Commentators and writers who mocked it now pay their bills by covering it. T20 cricket has been accepted as a vibrant, nuanced, form of cricket, helped by figures such as Eoin Morgan, who was ahead of the curve in recognising the IPL’s importance in player development.

There are parallels in English football. Over the last few years, it’s become commonplace for teenage talent to leave the reserve sides and substitute benches of the UK, and seek out opportunities abroad. The most notable of these, Jadon Sancho, left Manchester City over fears he would be denied chances in the first team, and headed to Borussia Dortmund – where he has flourished, and forced his way into international contention. The tactical and technical benefits of training and learning in a different culture, hearing different voices in a new and intense environment, don’t need to be restated.

In terms of Curran’s actual place in the England XI, there are a few issues. Directly replacing Moeen at No.7 would, given the lack of a viable backup, leave England with only one spinner. It’s hardly an outrageous move to omit a second spin option – and we have seen Morgan do so, memorably, in the ODI World Cup last summer – but it does leave them a touch one-dimensional, particularly against left-handers.

While No.7 is the obvious spot for Curran to slide into the batting line-up, there’s also the question of where Curran would sit in the bowling order. Fans who mainly follow Test cricket will have an image of Curran as a classic new-ball swing bowler, but in recent T20s he’s been ineffective in that role. Since the start of 2019, no established bowler in the world (min 300 deliveries) has a worse Powerplay strike rate, or bowling average, than Curran. Given that half of his bowling has been done in that phase, you’d be concerned.

However, England seem to have moved away from the idea of a swing bowler as their new ball option. In Overs 1-4 against Australia in their most recent series, Morgan used Archer and Wood (going all out express pace as their default attacking option) in 11 of the 12 overs. Three wickets in 66 balls was a broadly successful return on the strategy, and it seems unlikely that they will disrupt it with Curran. Practically, in this current England side, Morgan needs Curran to bowl through the middle overs, or be a matchup option exploiting recognised weaknesses in specific opposition players. Helpfully, Curran is more effective against left-handers than right-handers, both in terms of attack and defence; this allows him to bowl the overs which Moeen may have originally bowled, given the off spinner’s preference for bowling at lefties.

It isn’t a direct fit, of course – plenty of batsmen would happily face any seamer than an off spinner taking the ball away from them – but it’s a more natural fit than it could be.

Curran’s first IPL wicket was Steve Smith; his most recent was Virat Kohli. In between, he has dismissed David Warner, Quinton de Kock, among plenty of others, none of whom would be typically gracing the Blast. In the past, Curran may have entered international T20 cricket and been overawed when faced with the best in the world; as and when he does take his place in the XI, his overseas experience should prevent this. Curran exists as a very obvious example of how a cricket board, and a cricket team, can benefit from allowing their players to travel and take in the world, to see the game beyond their borders.