Ben Jones analyses two of the more extreme English batsmen of the last few years.

Ben Jones is an analyst at CricViz

Style and substance. It’s the central conflict which cycles through in the background whenever we talk about cricket. There it is, looping through our words as we casually talk of there “being something about him”, or of someone “just getting the job done”. It’s there when we talk about grit, about class, about skill and survival. Substance, and style.

It’s ingrained in the way we talk about even the finest players, dividing the most rounded performers into one of two camps. Cook and Pietersen, Dravid and Sehwag, Smith and Amla. One of the most apposite cricketing observations of the modern era was that between Steve Waugh and Mark Waugh. You’d want Steve to bat for your life so you could spend the rest of it watching Mark. Two great players, brought together as brothers and teammates, but separated by this almost philosophical difference.

James Vince bats against Australia in Brisbane, November 23, 2017

James Vince bats against Australia in Brisbane, November 23, 2017

On the opening day of the last 2017/18 Ashes series, James Vince made 83 runs. Against Mitchell Starc, Pat Cummins, Josh Hazlewood and Nathan Lyon, he strolled around the Gabba like he owned the place, playing cover drives which were of appropriately late-night viewing for the England fans back at home. It was a glimmer of hope, eventually snuffed out by Nathan Lyon’s balletic run out. England stumbled, fell apart. They lost 4-0.

The issue with run-outs is that you get no closure. It’s too easy to deny that, essentially, no bowler got Vince out. In some parallel universe, he’s still batting, still dominating the then best attack in the world.

In this actual universe, he’s certainly not still batting. He’s not even playing for England. On the opening day of this Ashes series, Vince will likely be at Chelmsford, readying himself to play Essex in the T20 Blast. Rather different surroundings to the Gabba.

His replacement in the England team, if not directly, is Rory Burns. On the face of it, you couldn’t find a player more different. Vince awaits the ball stood almost perfectly still; Burns sets up with almost trademark oddness, head and elbows twitching like a getaway driver keeping a keen eye out for the police. Burns’ case for Test selection was built on thousands and thousands and thousands of runs in the County Championship, while Vince’s was built on a perceived sense of class and almost unlimited potential. Vince was picked for his style, Burns for his substance.

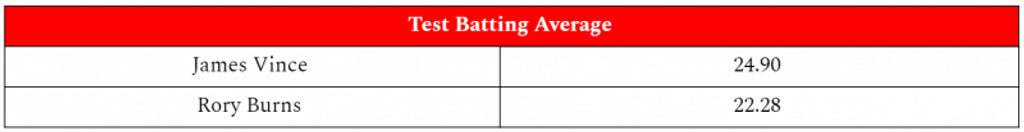

Yet right now, they average almost exactly the same in Test cricket. One has a high score of 83, the other of 84. One is dismissed every 49 balls they face, the other every 50 balls.

In some ways, that’s to be expected. Both have faced almost exactly the same quality of bowler in their Test career to date. The combined bowling average of everyone Vince has faced in Test cricket? 30.88. The same figure for Burns? 30.93. They have faced a similar calibre of attack, and have produced similar results.

What’s more interesting, is that they have gone about it in very different ways. Not just in the shots they have played, though that is stark – against pace, Vince drives one in every seven balls, while Burns drives one in every fourteen – but in the type of deliveries which have dismissed them.

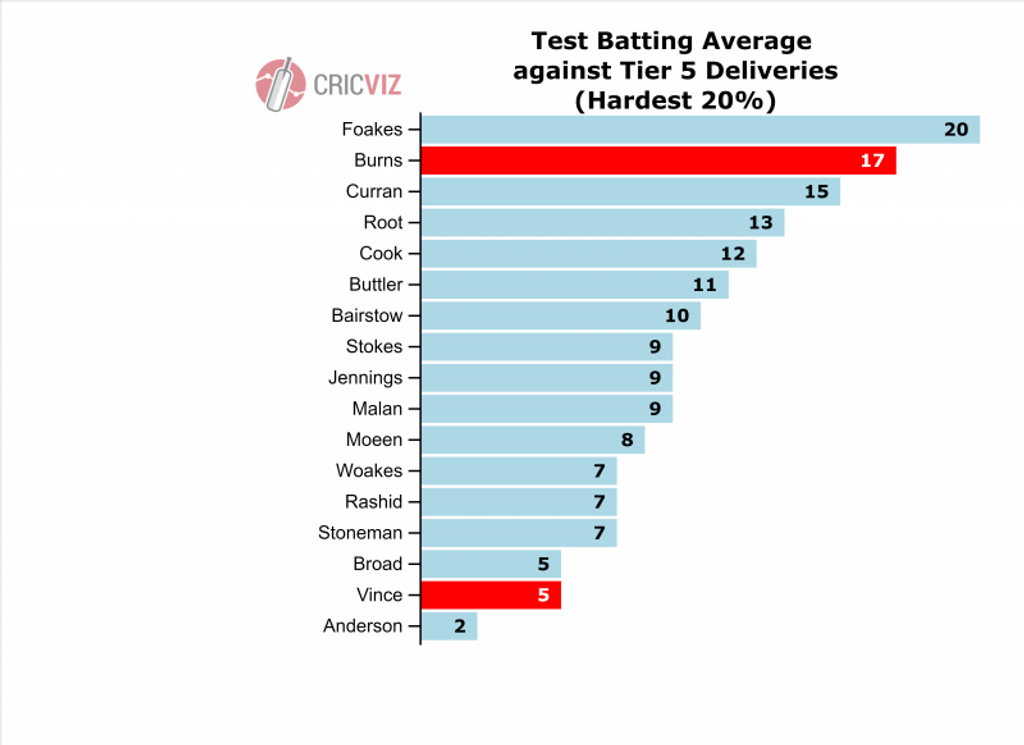

Our Expected Wickets model uses ball-tracking data to work out the likelihood that any given delivery is going to take a wicket, or lead to runs. It allows us to put every ball in Test cricket into a little bucket of quality, to divide it up according to how threatening it was. Tier 1, the easiest 20 per cent, all the way up to Tier 5, the hardest 20 per cent. Thus, we can see whether a player tends to get out to very good balls, or to mediocre ones. JaffaViz, if you will. In this specific way, the difference between Vince and Burns is illuminating.

Burns is actually very good at keeping out the good balls. Extremely good, in fact. Of all England’s players recent players, only Ben Foakes averages more than Burns against the hardest tier of deliveries, against the absolute cream of the crop. Something in the water at The Oval, perhaps.

And yet, Burns really struggles against deliveries he should dominate. Against the far easier Tier 1-4 deliveries, he averages just 28. Against easier deliveries, he’s worse than Anderson; against harder deliveries, he’s better than Root.

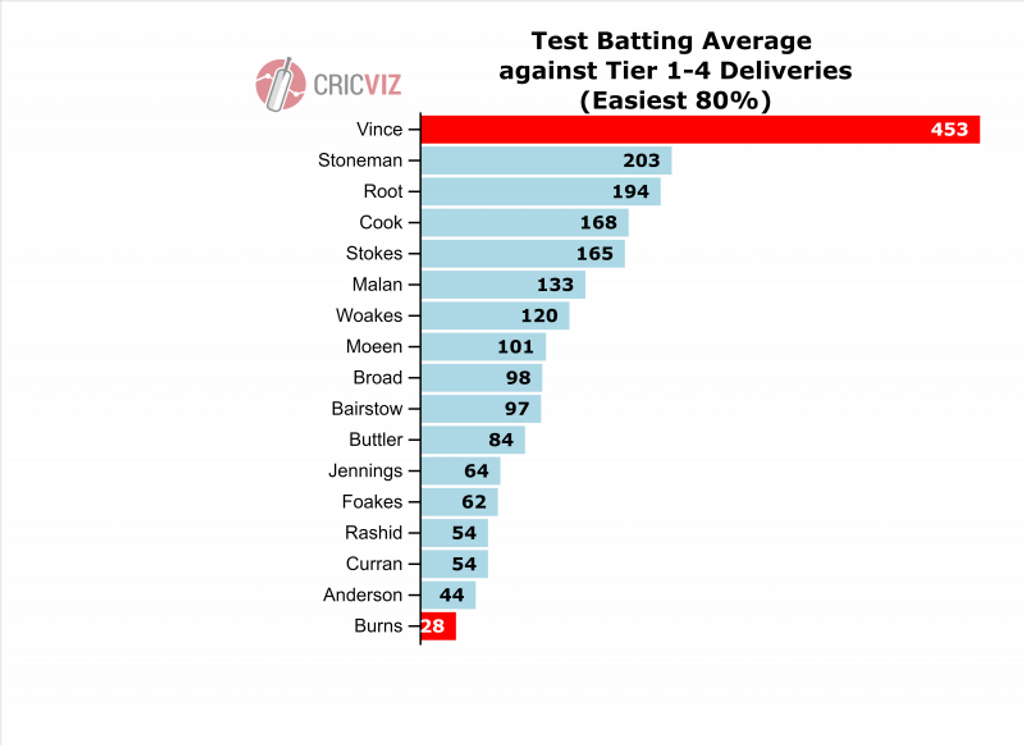

As you can see, Vince is the opposite. None of England’s recent players are more effective against Tier 1-4 bowling, nobody else more capable of bullying the vast majority of deliveries sent down. In this respect, he is a class apart – but he can’t keep out the good ones.

Part of the reason for this is exactly what you’d think, holding the cliched image of Vince in your mind. The average batsman only attacks 25% of those genuine jaffas, while Vince insists on attacking 34%. It’s not an enormous difference, but it’s a significant one. It points towards the broader difference between these players, and how we talk about them.

This is a question of aesthetics. A certain group of fans and pundits give Vince more credit and leeway because he looks so effortless, as if he barely needs to try. By virtue of the fact he is so untroubled by the majority of bowling in Test, he looks superb the vast majority of the time. And he averages in the mid-20s.

Burns averages 22.28 with the bat from his 14 innings in Test cricket so far

Burns averages 22.28 with the bat from his 14 innings in Test cricket so far

A certain group give Burns more credit because it looks like he’s really, really trying. There’s so much obvious concentration and thought, a technique that has been constructed to help him deal with the toughest challenges thrown his way. It’s an unusual method, which means he gets out in unusual ways, to unusually “easy” deliveries, but he keeps out the unusually hard ones. And he averages in the mid-20s.

The point is, it’s important to assess the qualities that batsmen’s quirks and peculiarities actually give them. Burns’ technique is almost perverse, but it means he can dominate balls that others don’t. Vince’s technical excellence means he essentially doesn’t get out unless you bowl a great ball. There is substance to Vince’s style, and style to Burns’ substance. Each have a method which has got them this far, and perhaps understanding what they’re both good at, what they’re better at than any other English player, allows us to give them the credit they deserve, and give them a better chance of succeeding.