In the 2019 edition of the Wisden Cricketers’ Almanack, Jonathan Liew traced the history the three-figure score in cricket – perhaps the game’s most celebrated feat.

In his 1977 book The Domestication of the Savage Mind, the anthropologist Jack Goody visits the LoDagaa people of northern Ghana, who possess a unique system of counting. While large items such as cows are numbered singly, smaller items – particularly the cowrie shells that are used as common currency – are not. The locals first take a handful of three, then of two, and make a pile of five. Four piles of five make 20, and five piles of 20 make 100. When Goody asks the LoDagaa how they count, he is met with bafflement. “Count what?”

In other societies, numbers are tied to objects. In some of the Fijian islands, ten is bola when describing boats, boro when describing coconuts. The Tsimshians of north-west Canada have different words for three: gulal for men, galtskan for trees, guant for garments. And the Nivkh of Sakhalin Island in eastern Russia have over 30 classes o fnumber, each pertaining to an – often maritime-themed – object. The number five could be thory (referring to people), thovr (places), thosk (poles for drying fish), thor (bundles of dried salmon slices), or plenty else.

We like to think of numbers as natural, abstract, objective and the same for everyone. In fact, they are man-made, and invariably laden with context, history and heritage. Even English is littered with words – quartet, dozen, score – that evoke a number but are not directly interchangeable with it. We can talk about a brace of pheasants, even a brace of goals, but walk into your local railway station and ask for a brace of singles to Swindon, and you will likely be invited to rephrase yourself.

All of which brings us to the batsman’s century, which in 2019 celebrates its 250th birthday: one arbitrary measure of commemoration marking another, you might think. We’ve come a long way in the quarter of a millennium since John Minshull recorded 107 notches for the Duke of Dorset’s XI against Wrotham, a period in which the simple act of scoring 100 runs has assumed totemic significance: not simply a measure of achievement or a basic unit of sporting currency, but an article of faith, perhaps even a yardstick of cricketing citizenship. Scoring ten or 30 or 80 means nothing beyond itself. Make a century, on the other hand, and – even if you do nothing else in your career – you have inducted yourself into a special fraternity.

Sir Jack Hobbs scored a staggering 199 first-class hundreds – the most in the game’s history

Sir Jack Hobbs scored a staggering 199 first-class hundreds – the most in the game’s history

We know little about Minshull’s century. We don’t know what the weather was like, what the pitch was doing, who won the toss, who bowled, how many Wrotham scored, or who won. What we do know is that, at some point on August 31, 1769, during ‘second hands’, as the second innings was known, the first wicket fell, and Minshull stepped out to join his employer, the Duke of Dorset.

Minshull was a gardener in the country house of Knole in Kent, supplementing his eight shillings a week by playing in the Duke’s matches. He would have been in his late twenties, and according to John Nyren was “a thick-set man, standing about five feet nine, and not very active”.

Nor was he elegant or self-effacing. As Nyren recalled in The Cricketers of my Time: “His position and general style were both awkward and uncouth; yet he was as conceited as a wagtail.” But over the course of what we can assume was an afternoon, Minshull scored four fours, nine threes, 15 twos and 34 singles: all run, and all from rolled or lobbed underarm deliveries slapped with a curved bat. It is the first surviving stroke-by-stroke record of a match: a rare written artefact in an age when the primary method of scorekeeping was carving notches into wood.

Minshull’s century might not, in fact, have been the first. The previous summer, the Reading Mercury reported that John Small “fetched above seven score notches off his own bat” for Hambledon against Kent – though it’s impossible to say whether this was over one innings or two. In any case, cricket in the pre-Victorian age was a leisure pursuit rather than a codified sport: what survives of it today is probably a fraction of what existed.

Minshull’s achievement did not appear in newspapers, which suggests such feats were either unremarkable or largely unrecorded. Had the historian John Goulstone not happened upon it in archives in 1959, it might have remained forgotten. And so, much as ‘first-class cricket’, ‘Test cricket’ or ‘the Ashes’ only really emerged ex-post facto, reverse-engineered in the service of an existing mythology, it wasn’t until the late 20th century that Minshull’s hundred came to be regarded as the first – despite the fact that it was more than 200 years later, and that Minshull himself might have been blissfully unaware he was doing anything momentous at all.

To explain how this came about, we need to understand how numbers function in societies: what significance they take on, and why. Minshull’s is also a story of cricket’s evolution from a game of untamed fields and betting ledgers, where the only statistic of relevance was who won and lost, to a game in which the upkeep and pursuit of personal statistics and milestones became a sport-within-a-sport – a development without which, dare we imagine it, Wisden might not exist.

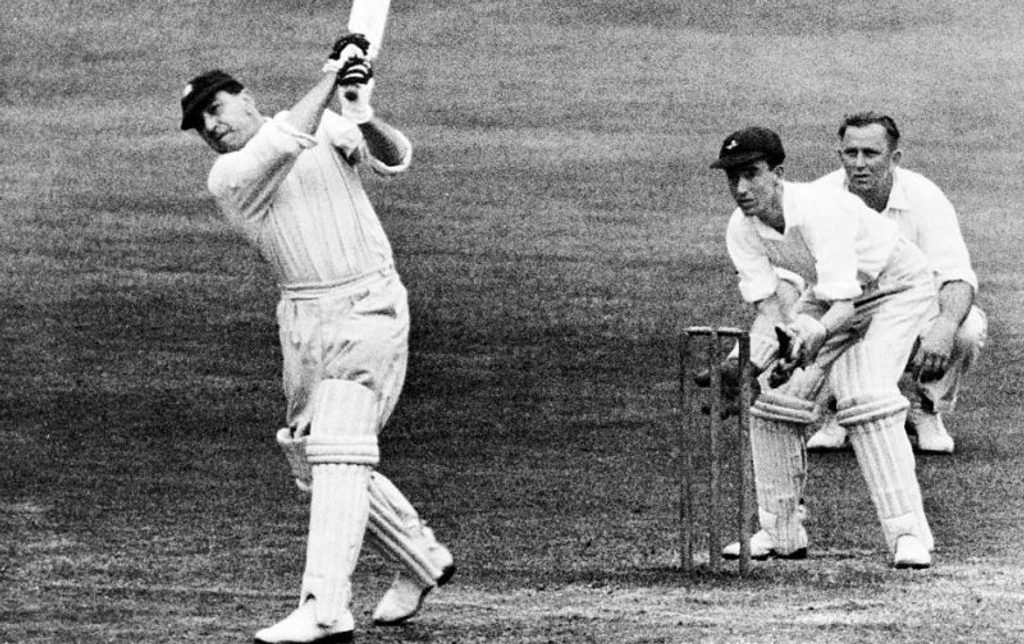

Wally Hammond registered 167 hundreds from 1,005 first-class innings

Wally Hammond registered 167 hundreds from 1,005 first-class innings

There’s a common assumption that the reason we count to ten is because we have ten fingers. Yet base-ten has been just one of many counting systems. The ancient Babylonians used base-60, the Mayans base-20. “People generally fancy that, if a child was raised by wolves, he would come to the idea of counting just by looking at his hands,” writes the archaeologist Denise Schmandt-Besserat in Before Writing: From Counting to Cuneiform. “Cross cultural linguistic and anthropological studies on numbers show, however, that in all parts of the world, many societies could survive without having number words beyond ‘three’.”

Certainly Britain in the imperial, pre-industrial 18th century, a place still wedded to furlongs and bushels, seems to have borne no affinity for powers of ten: the Mercury’s description of Small’s 1768 innings – “above seven score notches” – is telling. Leaf through contemporary newspapers, and “century” is deployed solely as a period of time.

It’s not until around 100 years later that the concept of a century as a hundred runs begins to take hold. The phrase is barely seen at all in a sporting context until the 1860s, and even then it often sits within quotation marks, denoting its quirky status. “Another great feature of the month has been the wonderful play of Mr W G Grace,” trills The Graphic in August 1870, “his scores far more regularly exceeding ‘a century’ than falling short of that number.”

So what happened in the interim? For one thing, centuries became more common. The advent of roundarm bowling kept scores low until the mid-19th century, at which point batsmen began to adjust, and broke free. It took 66 years to record the 100th first-class hundred of the 19th century, another six to record the 200th. As the game tilted in batsmen’s favour, a new argot grew up around them. At its centre was a simple, heroic achievement that prince and pauper alike could understand: the ‘century’.

There were broader forces at work, too. A large portion of the general population in Minshull’s time was innumerate. The Industrial Revolution changed that. A firm grasp of arithmetic had long been a requirement for the ruling and military classes, given the importance of navigation, cartography, ballistics and architecture. But the following decades would see a partial democratisation of numbers.

“By around 1800,” notes Professor Tom Archibald, a maths historian from Simon Fraser University in Canada, “the demand for people who could do accurate reckoning was high. A good knowledge of basic mathematics was a key to social mobility for those not born into wealth.” It was also around this time, Archibald notes, that scoring games, such as cricket, began to take precedence over more traditional sports, such as boxing or cockfighting.

Cricket now had a numerically engaged audience, interested in more than who won or lost. The migration of scorekeeping from knife and wood to pen and paper allowed for all sorts of statistics. In 1846, Lord’s introduced its first telegraph scoreboard and sold its first scorecards. Until then, the only way for spectators to divine the score – unless they kept it themselves– was when both scorers ceremonially stood up to indicate the sides were level.

This wasn’t just about keeping score. It was about creating a mythology, birthing a culture, negotiating the tokens and totems that would sustain cricket through its growth years and beyond. As the sport mushroomed in the 1860s, hastened by the spread of the railways, fuelled by the publishing boom and nourished by the emergence of Grace, the century was incorporated into cricket’s epic narrative: rare enough to be heroic, common enough to keep drawing crowds, simple enough that anybody could grasp it, and resonant enough that people could bond over it.

Newspapers began to publish scores and averages; the arrival of almanacks such as Wisden and Lillywhite’s fulfilled the mid-Victorian thirst for record-keeping and statistical ephemera. By the time Grace became the first player to record a 100 hundreds, in 1895 – an event commemorated with a leader in The Times and a letter from the Prince of Wales – the pursuit of the century had woven itself into cricket’s culture. Like the LoDagaa’s cowries or the Nivkh’s fish-drying poles, the century elevated itself above other methods of counting by simple virtue of what was being counted.

For much of the summer of 2008, a small but dedicated press corps traipsed up and down the country hoping to see Mark Ramprakash score his 100th first-class hundred. His 98th had come in the middle of April, his 99th at the start of May. And yet, as July became August, he was still waiting: irritation turned to bemusement turned to frustration turned to mild anger. After being dismissed in a Twenty20 game at the Rose Bowl in June, Ramprakash had taken exception to a Sky cameraman tracking him back to the pavilion, and lashed out with a fusillade of four-letter words, forcing Surrey staff to intervene.

Mark Ramprakash

Mark Ramprakash

Though he finally got there on August 2 at Headingley, he had been labouring under one of the oldest ailments in the game. If scoring 100 constitutes a form of batting perfection, then 99 may be its polar opposite: the least satisfying number on which to be marooned, with its sense of incompleteness. Such is the weight of the century that even to approach it is to subject oneself to its unique and turbulent gravitational field. A hundred years earlier, Tom Hayward had merrily hewn his way to 99 centuries, before grinding to a halt. For more than a year between 1912 and 1913, he toiled away in search of the 100th, only to come unstuck 46 times in a row.“It is said that he has even worried himself about the crowning of his many batting triumphs in the way that he desired,” reported the Athletic News.

The nervous nineties, then, is no recent phenomenon. In 1897, KS Ranjitsinhji was lamenting the tendency of batsmen to get anxious as they neared a milestone, which he attributed to the institution of “talent money”, an early form of performance bonus. “Most counties give their representatives a sovereign for every 50 runs they make,” he wrote in The Jubilee Book of Cricket. “Naturally this makes them all the more anxious when they approach the required totals. That sovereign causes innumerable run-outs and rash strokes.”

Talent money may no longer feature, but the incentive to hit three figures remains as strong as ever. As numerous studies by psychologists and behavioural economists have proven, the brain gets lazy when processing numbers. It knows the digit on the left is the most important, so that’s where it starts reading.

This is why, towards the end of the 19th century, American businesses realised that pricing goods with “99” on the end made the cost look smaller. And in sport, the eye is similarly drawn to round numbers: 100 uses more digits than 99, and therefore looks more imposing. This partly explains why the century has assumed such worth. But 100 runs also feels like a satisfactory measure of batsmanship: it generally means batting against at least four different bowlers, for at least a couple of hours – a test not simply of skill and patience, but of stamina and adaptability.

You might surmise then, as Ranji did, that batsmen edging towards the milestone are more susceptible to mistakes. Yet the reverse is true: the evidence suggests that batsmen in the nineties tend to play more cautiously. A Test batsman who reaches 95 is almost 10 per cent more likely to be dismissed between 100 and 104 than between 95 and 99. The contrast is even more pronounced in one-day internationals, where the disparity is almost per cent. Meanwhile, a 2015 study by researchers at Queensland University of Technology discovered that batsmen’s strike-rates slow as they approach their century, then speed up again once they pass it.

On 16 March 2012, Sachin Tendulkar became the only batsman to register hundred tons in international cricket

On 16 March 2012, Sachin Tendulkar became the only batsman to register hundred tons in international cricket

Perhaps our attachment to centuries speaks to something quintessentially human in us. In the 250 years since Minshull, the achievement has gone from an unfathomable pinnacle to a regular occurrence. Still, though, it beguiles us, subverts the rational and gnaws at the emotional, spins us into its web of numbers, plays on our craving for neatness.

One of the virtues of short-form cricket is the way it has returned the century to a realm of wonder it hasn’t inhabited since the early 1800s. There were just 36 centuries in the first 14 years of T20 international cricket, and even if they’re arriving at a quickening rate, they still feel cherishably rare.

As scoring rates rise, as boundaries creep inwards, as public culture demands ever more constant commemoration, ever more perpetual memorialisation, ever greater meaning – remember the confected hoo-ha a few years back over Sachin Tendulkar’s 100th international century? – perhaps T20 will act as a sort of natural corrective, the format that put the century back on its pedestal.

Meanwhile, there’s an irony in the fact that in 2018, when the ECB were casting around for a shiny gimmick that would distinguish their new shortform competition and simplify the game for a new audience, they settled on The Hundred: 100 balls a side, a scoring system so universally resonant that even the LoDagaa, the Tsimshians or the Nivkh would grasp it. In more than one sense, we may be coming full circle.