From the archive: Anjali Doshi examines India’s ‘happy state of mind’ and the myth that Indians love cricket.

This article first appeared in issue 3 of The Nightwatchman, the Wisden Cricket Quarterly

Buy the 2018 Collection (issues 21-24) now and save £5 when you use coupon code WCM9

First published in The Nightwatchman in 2013

I have never cared less about Kant’s categorical imperative than I did on March 13, 1996.

At about 2pm on a Wednesday, in the examination centre in Mumbai for the Higher School Certificate – a public examination equivalent to the A Level in England – I was meant to be focusing on the Philosophy paper in front of me. But the only thing on my mind as I studied the questions was, “I wonder who won the toss.”

News filtered in – through an errand boy roaming the hallways – that India had put Sri Lanka in to bat, that Jayasuriya and Kaluwitharana were out, that the score was 1 for 2… It was all happening, as Tony Greig was probably saying that very moment on commentary. “This is terrible,” I thought. “Now, I can’t concentrate at all.”

The rest of my time in the examination hall is a daze. But I do remember it as the only instance in about 20 years of writing tests that I left early as I bundled into a waiting taxi.

The streets were deserted except for crowds gathered outside electronics’ stores – noses pressed up against, and heads poking through, the large glass windows – and crouched around paan beedi (betel leaf and tobacco) shops to listen for updates on the transistor.

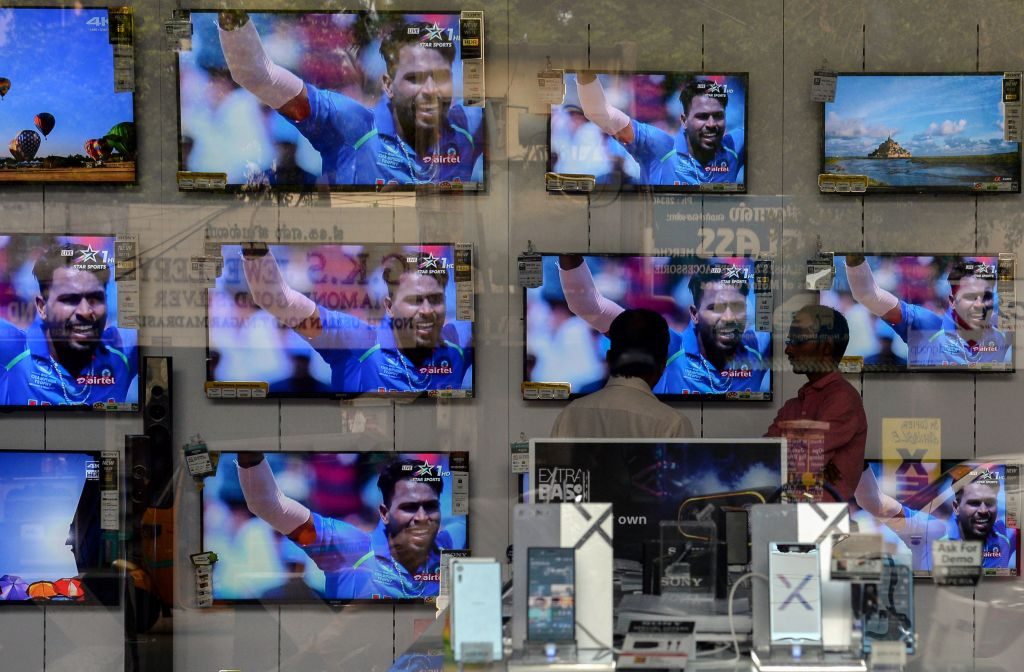

The 2017 Champions Trophy final between India and Pakistan is shown on televisions at an electronics showroom in Chennai

The 2017 Champions Trophy final between India and Pakistan is shown on televisions at an electronics showroom in Chennai

Cell phones had just made their entry into India but at Rs 32 (about 25p) a minute per call were hardly the ubiquitous entity they are now. The taxi driver, who had been following the action on the radio, provided an update, “206 for 6. de Silva 66.” I made it home just in time to see the Sri Lankans get to 251.

“Khallaas! (finished)” declared my dad who is forever the prophet of India’s cricketing doom. I argued the only way to beat the Sri Lankans at their game was to put them in to bat after the massacre at the Feroz Shah Kotla, where they chased down India’s score of 270-odd earlier in the tournament. “The ball is turning. India will lose. Azhar is an idiot,” he said.

My dad, I must elaborate, is the most exasperating cricket lover I have ever shared a couch with – constantly overestimating the opposition, compulsively criticising the Indian team as he shouts his advice, and always preparing for the worst, which basically involves rushing to hide in his bedroom each time the opposition hits a boundary or an Indian wicket falls.

My mum, who has no patience for anyone wasting precious hours on flannelled fools – and worries constantly about this foreign conspiracy to impede India’s economic growth – is quite naturally inclined towards supporting the opposition.

Arjuna Ranatunga batting during the 1996 World Cup semi-final

Arjuna Ranatunga batting during the 1996 World Cup semi-final

As the sun sank into the sea that evening, it seemed my parents were pragmatic enough to anticipate the horror that would unfold on television, a horror that is still very fresh. Those numbers are stuck in the head: 251, Aravinda’s 66 from 47, Sachin’s 65, India’s 120 for 8 when the match was abandoned. I don’t need to refer to the 1996 World Cup semi-final scorecard to double-check the scores. But when I do, it still hurts to see: “Sri Lanka won by default”.

***

That day, for me, epitomises the very best and worst of Indian cricket. The hold cricket has on the nation as it wipes life off the streets, a bond that unites family members who may have little else to talk about, a sense of identity that infuses a billion with purpose, confidence and self-worth in their collective consumption of a new age opium and new age idols, and a balm that soothes our deepest scars.

But there was also the backlash of a deflated nation who set the stands on fire, burnt its superstars’ effigies, decreed the Indian team the worst in the world, accused its heroes of throwing the match, cursed its beloved Sachin Tendulkar, and switched off its televisions as defeat loomed, unable to bear the loss and what it said about them.

From one game to the next, from Bangalore to Calcutta, the headlines changed from, ‘Nation Erupts in Joy’ to ‘A Nation Shamed’.

There have been many such days before and after that one at Eden Garden. And there will be many more. It is hard to decide, to paraphrase writer Mike Marqusee, which brings out the worst in India’s cricket nationalism: victory or defeat.

Each World Cup has brought us to a closer understanding how Indians view themselves through the prism of their team’s performance. If 1983 was the triumph of the underdog and 1996 a nation shamed, then 2003 was a confident stride in the right direction, 2007 a lesson in overconfidence and 2011 a nation whose time has come.

“As globalisation strides forward, the search for national identity becomes ever more desperate and ever more dominated by the hostility to perceived national enemies, both within and without the country’s borders,” writes Marqusee in War Minus The Shooting – his portrait of the subcontinent during the ‘96 World Cup. “The carnival of globalisation turned into an orgy of nationalism.”

Never was this nationalism, or brazen flag-waving, more apparent than on the night of April 2, 2011 as India poured on to its streets to celebrate what each Indian deemed a personal triumph. The most viewed sporting event on television was followed by the longest celebration in sporting history, a postscript that closes Beyond A Boundary, a recent documentary following the lives of three cricket-crazy protagonists in the backdrop of the 2011 World Cup.

Social and cultural historians have been hard-pressed to find a parallel elsewhere of a sport that has inadvertently become the torchbearer of a nation’s aspirations. Jamaica and sprinting, China and basketball, Brazil and football, but none offers both: an enormous population and a unanimous obsession.

***

Indians are mad about the game. Sometimes I do think they are mad. But the unbridled passion is infectious.

– Don Bradman

The only time Bradman ever visited India was when his plane stopped to refuel in Calcutta en route to England where he was to cover the 1953 Ashes. When word spread, courtesy of the airline staff, thousands gathered at the Dum Dum Airport for a view.

An India cricket fan holds a sign paying tribute to the late Sir Donald Bradman, 2001

An India cricket fan holds a sign paying tribute to the late Sir Donald Bradman, 2001

Sixty years after Bradman visited, the general perception in India and outside remains the same.

But consumer research and television audience measurement increasingly suggest it is a fallacy to call India a cricket-loving nation. The majority is interested either in associating themselves with a victorious Indian team or in the entertainment events like the Indian Premier League provide.

A senior television executive tells the story of one of the Who Wants to be a Millionaire? creators who flew down to Mumbai from England to discuss the idea of cricket-based version of the show after the ground-breaking success of its Indian version Kaun Banega Crorepati. He pitched a cricket KBC to the Indian rights holders, only to return home a dejected man when he found no takers because market research suggested very few Indians would be interested in the concept or have the knowledge.

A phenomenon first noticed during the 2006 Champions Trophy – when India hosted a global cricket tournament after a gap of 10 years – saw several matches not featuring India played to empty stands, prompting former Wisden editor Scyld Berry to remark, “Cricket in India is not a religion, as has been said, nor is one-day cricket. Only one-day cricket involving India attracts public attention.”

Several television industry executives agree. “Indians do not love cricket,” says Sneha Rajani, senior executive vice-president and business head, Sony TV, the company that holds the rights to the IPL till 2017. “There is little or no interest in games that do not feature India. So you might say they love Indian cricket. But there is also very little interest in a game India is losing.”

Indian Border Security Force (BSF) personnel watch a live broadcast of the Cricket World Cup

Indian Border Security Force (BSF) personnel watch a live broadcast of the Cricket World Cup

A quick comparison of television rating points or TRPs – by no means an exact science but a fairly accurate guide to India’s viewing habits – recently showed a rating of 0.2 for the last day of the first Ashes Test at Trent Bridge in July, a Sunday of many twists and turns as England snuck home by 15 runs. Just 10 days later on a Wednesday, the second ODI between India and Zimbabwe revealed a rating of 0.5.

It’s telling that an inconsequential series won 5-0 by India achieved higher ratings than one of the most dramatic Ashes Tests of all. A TRP of 0.1 (roughly about 100,000 viewers) has been the average viewership for what Star Sports has been marketing as ‘Test cricket’s greatest rivalry ever’. Even the Wimbledon in June garnered more viewership with a rating of 0.3.

The India-Australia Test series earlier this year enjoyed higher ratings than the Test series against England last year, despite the England series being much more closely contested – the general trend shows that the minute India start losing a key match, ratings for general entertainment channels spike as people switch off from the cricket.

So positive was the impact of the 4-0 drubbing of Australia that it resulted in more interest in the IPL this year than in 2012, after India had lost eight consecutive Tests in England and Australia, and delighted, the IPL rights holders because the “happy state of mind” of the Indian cricket fan would mean more business.

***

In a recent study conducted by the Consumer Insight Division of Star Sports – the Rupert Murdoch-owned network that acquired rights to all cricket in India between 2012 and 2018 – the team attempted to understand the kind of cricket programming one must create for the Indian public.

“With about a billion dollars being invested by advertisers every year, it is important to have an insight into certain trends,” says Jasdeep Pannu, senior vice-president of sports marketing at Star Sports. When the mood is buoyant after a win like the World Cup or the 4-0 thrashing of Australia, the after-effects of this “happy state of mind” are visible: advertisers are more than willing to pay up to 20 percent more because they know the Indian public will tune in.

The psychographic portrait – not a thorough data-driven study but a rough guide – revealed three categories of cricket-viewers in India: players, disciples and fans. The players – those who have played the game at some level, have a deep appreciation for its nuances and are largely unaffected by India’s wins and losses – account for about 5 million of India’s total population. The disciples, who also follow Indian cricket closely but whose emotions are tied in very strongly with India’s wins and losses, account for about 50 million. And the fans, categorised as BIRGs because they bask in the reflected glory of India’s victories and disassociate when the team is losing, form the rest at about 65 million.

This research explains the IPL’s immense success despite a string of scandals – none worse than the fixing controversy this year. The racy domestic Twenty20 league with a thrust on Bollywood and entertainment, featuring international stars and occupying a primetime slot is viewed purely as a tamasha (spectacle) that involves little emotional investment and holds no threat of national shame. The IPL ratings for 2013? An average of 3.5 over 76 games.

Following a successful first edition, Sony TV came up with the tagline Ab Kabhi Nahin Harega India (Now India can never lose) in 2009. The tournament moved to South Africa for political reasons and the line had to be dropped but Sony’s executives have not given up on the idea just yet.

***

“While India was a colony, cricket was a means of settling accounts with the rulers. After Independence the new nation came to identify cricketing prowess with patriotic virtue. No other sport can play this role. In seeking the emotional allegiance of Indians, cricket has entered into an amiable competition with the Hindi film.”

– Ramachandra Guha in A Corner of a Foreign Field

Perhaps the cue to the genesis of this search for national identity lies in understanding the popularity of Amitabh Bachchan. The country’s most famous superstar burst into prominence as the angry young man of the Indian screen – the lower-middle or working-class hero from Mumbai’s slums, out to fight a lone battle against a corrupt and unjust system.

Bollywood actor Sushant Singh Rajput poses with then India captain Mahendra Singh Dhoni, 2016

Bollywood actor Sushant Singh Rajput poses with then India captain Mahendra Singh Dhoni, 2016

Twenty-five years after Independence, a nation disillusioned with the imposition of the Emergency (1975-77), the license raj, unemployment and labour conflicts, was searching for new heroes and hope. Bachchan’s character, always known as Vijay (victory) in this anti-establishment brand of cinema, became the icon of protest against India’s ills.

Since India’s 1983 World Cup victory and post-liberalisation, cricketers more than Bollywood stars have taken over as representatives of the nation’s global aspirations, and none more than Sachin Tendulkar. Through the 90s, Tendulkar alone drove television rating points up and down, perhaps like no other cricketer in India and the world, as he typified this phenomenon of India’s “happy state of mind” based on how many runs he scored – or did not.

This emotional dependence on Tendulkar changed significantly in the last 10 years as India began performing better overseas and enjoyed its most successful decade in cricketing history. And it explains why cricketers, who hail from small-town India like Mahendra Singh Dhoni and Ravindra Jadeja as well as posh urban pockets like Virat Kohli, market everything from Cola to cement, and even English Premier League football.

As for Test cricket’s greatest rivalry, forgive my fellow Indians if they reach for the remote.