Wisden Cricket Monthly reviews editor Jon Hotten on the latest book releases.

Jon Hotten tweets @theoldbatsman. Read his reviews in Wisden Cricket Monthly

Books of the month

Cricket 2.0

By Tim Wigmore and Freddie Wilde

Polaris, £17.99

Keeping Up

By Michael Bates and Tom Huelin

Into Words, £11.99

Ray Kurzweil, the American futurist who proposed the Law Of Accelerating Returns, calculated that the rate of progress of the entire 20th century was achieved between the years 2000 and 2014. It feels as though cricket has been through the same sort of exponential growth, outstripping a hundred years of play since 2003 and the birth of Twenty20 cricket. The ramps, scoops, switch hits, knuckle balls and ambidexterity are the most obvious and immediate manifestations of its impact; these books, in their individual ways, consider the wider terrain.

It is part of cricket’s intrinsic genius that it can be played over three hours or five days, yet a game that once crossed the world by boat exists in an accelerating culture and must meet its demands. It is about to be confronted by the first generation that do not remember cricket without T20. The thread they pull on stretches back into time. Two players quickly identified by Tim Wigmore and Freddie Wilde as shaping forces in the genre’s early years, Brendon McCullum and Chris Gayle, both have Test match triple hundreds (Gayle has two, of course). As Virat Kohli demonstrates, excellence in all formats is not only possible, but the mark of genuine greatness.

But by the end of Wigmore and Wilde’s absorbing, ideas-filled book, you feel that they are right to consider T20 cricket as and of itself, a format in which Gayle can make a hundred in eight overs playing for a team that didn’t exist at the turn of the century while being paid the kind of money that at first made him laugh and then enabled him to exist on his own terms as the Universe Boss. You feel for Jade Dernbach, one of many entertaining interviewees, when he says, “you could bowl six good balls and go for six boundaries. That’s how much it [the game] has changed”.

Chris Gayle: a T20 icon

Chris Gayle: a T20 icon

Throughout, Wigmore and Wilde throw out illuminating statistical examples that amplify the constant cause and effect that such a tightly wound format produces. The forbidding Gayle, for example, receives a wide or no-ball – ‘charity runs’ – every 19 deliveries, against an average of one every 35.

They consider too the isolating effects of the new lifestyle of the franchise player. Gayle constructs a persona via social media (“wherever you were in the world, whatever you were doing, Chris Gayle was having more fun than you…”) that exists next to a reality in which he says he can count the number of those loyal to him, “on one hand. And not even five fingers”. Dwayne Bravo characterises himself as, “an individual who plays a team sport”. The entirely wonderful Rashid Khan, whose rise to prominence would not have happened before T20, counterbalances those downsides.

Wigmore and Wilde end with 32 predictions of where T20 cricket will go, and it’s no surprise that there is only one direction of travel. The shorter the format, the more empirical each delivery becomes. Everything has an immediate and measurable consequence on and later off the field, and the weight and power of finance continue to strain the thread that connects it to the rest of cricket. T20 is an arms race that has only just got started, and Cricket 2.0 captures deftly the thrill and danger of horizons we are now only glimpsing.

“Bates’ supreme skill behind the dollies kept batsmen pinned in their ground”

“Bates’ supreme skill behind the dollies kept batsmen pinned in their ground”

It’s interesting that in their all-time T20 XI, Wigmore and Wilde decide against a specialist wicketkeeper (AB de Villiers has the gloves here). For a time Hampshire’s Michael Bates hinted at a new way forward, standing up to the stumps in a white-ball team that used crafty seamers to strangle the opposition. Bates’ supreme skill behind the dollies kept batsmen pinned in their ground. The sadness that his career ended because his own batting was not considered strong enough in the post-Gilchrist world was felt keenly among his followers.

One of those was Tom Huelin, for whom Keeping Up became a passion project. He and Bates have produced a book that’s part (auto) biography and part exploration of the notion that a specialist gloveman might become essential to the shorter form (given the higher percentage of the game that they can affect with their primary skill). Bates grew up in the same age-group teams as Jos Buttler and Joe Root, and the chapters on his sadness at having to let the game go just as their lives take flight are genuinely affecting. Towards the end of the book, he meets Gilchrist, the man who changed it all, and their chat is reproduced verbatim: as keepers they find much common ground.

You come away from these books with a feeling for how unforgiving and selective professional cricket is. There’s a strong sense of its internal dynamic, with everyone scrapping for their place beneath the kings of the game. It’s in finding the human stories below the skin that both of them come alive.

The round-up

There’s an old joke about how to make a small fortune from owning a football club – start with a large one. It often feels like the same applies to publishing, and especially the strange little niche of publishing books about cricket. As the ECB’s legendary research will tell you, there are lots of fans out there, they just don’t know it yet.

Tatenda Taibu was Zimbabwe’s first black captain

Tatenda Taibu was Zimbabwe’s first black captain

But the game is big, its supply of stories almost endless, the urge to tell them strong. Tatenda Taibu’s is among the most extraordinary. At 20 years old, he was Test cricket’s youngest captain, and, more significantly, the first black captain of Zimbabwe, appointed just months after Henry Olonga and Andy Flower had worn black armbands at the 2003 World Cup and were forced into exile by Mugabe’s thugs.

A year after his appointment, Taibu had retired in protest at the corruption endemic in the sport in his country and found himself in the office of a government minister being shown pictures of dead bodies, with the clear implication that he was next. He met a Zanu PF activist employed in cricket administration who admitted that his job was “to instil as much fear in me as possible”. Nonetheless, three years later, Taibu was back and making both Test and ODI hundreds before losing his prime years to Zimbabwe’s international exile and then retiring at 29 to follow his Christian faith.

He lives in Liverpool now, with his wife and sons, and plays club cricket for Formby. Keeper of Faith (deCoubertin, £12.99) offers the true power of a remarkable life, more hidden than it should be.

Franklyn Stephenson is another with a career somewhat lost in the realpolitik of the game, an all-rounder of bountiful talent and spirit born at a time of blazing fecundity in Barbados and West Indies cricket. In 1982/83, at just 23, he went on one of the benighted rebel tours of South Africa, and like all of his fellow tourists (but unlike those from England) was banned for life from representing his nation. It was the defining moment of a career retold in My Song Shall Be Cricket (Pitch Publishing, £19.99), a title that captures his evident love for the game. His legacy, alongside the thrills he offered fans at Trent Bridge, will be his pioneering slower ball.

The Skipper’s Diary (The Cricket Publishing Company, $59.99NZ available from www.theskippersdiary1949.com) is another labour of love, the love coming from Richard Hadlee and his brothers for their father, Walter Hadlee, the labour coming from Richard’s transcription of Walter’s diary of the 1949 New Zealand tour of England, handwritten in script so tiny he needed a magnifying glass to decipher it.

The book is coffee-table sized and richly produced, full of telling detail: Walter even kept immaculate record of his finances – he received £366 for his 244 days on tour, supplemented with nine pounds and nine shillings he made from broadcasting for the BBC and the nine pounds he left home with. The tour he led was a famous one for the country, too. All four Tests were drawn and 13 of 16 first-class matches won.

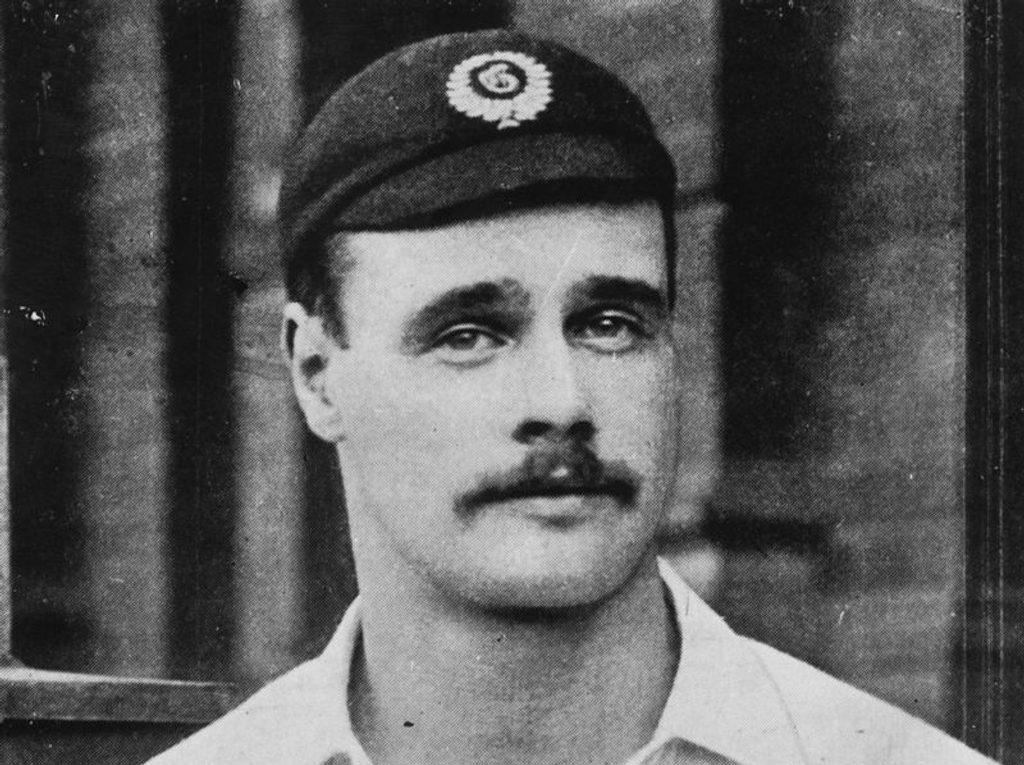

Gilbert Jessop, 1901

Gilbert Jessop, 1901

Some minutia of the Golden Age is David Battersby’s subject in his self-published The Early Years of Gilbert Laird Jessop (£12 from dave@talbot.force9.co.uk). Before ‘Jessop’s Match’ at The Oval in 1902, when he scored England’s fastest Test century, the golden youth bestrode the cricket fields of Cheltenham, where he was, as you’d imagine, quite handy. There are some lovely scorecards here, notably Churchdown v Churcham on June 7, 1890, a charged if one-sided derby game in which Gilbert knocked up a quick 75 from Churchdown’s No.3 spot before taking five wickets for no runs as Churcham were bowled out for 7. You can almost hear the conversations in the pub afterwards, as these records whisper up through time.

There’s an abiding sadness, of course, to Christopher Sandford’s The Final Innings (The History Press, £20), the story of the English summer of 1939 and the 52 first-class cricketers that did not return from World War II. It’s a sequel to The Final Over, his acclaimed account of cricket and the Great War, and the same, diligence, sensitivity and meaning of these stories exists here. There are diaries and letters that will break your heart, and the talk of 2019 as some kind of ‘last summer’ of cricket is put in firm perspective by his recreation of the 1939 season.

Jonathan Rice’s Stories Of Cricket’s Finest Painting (Pitch Publishing, £18.99) touches briefly on similar ground. Cleverly, he uses Albert Chevallier Taylor’s commission to paint Kent’s game with Lancashire in 1906 as a fulcrum for a sideways glance at the game’s first Golden Age. Two of the players in the picture would not survive World War I, but their stories and the fate of the picture, ultimately brought for more than half a million pounds and now hanging at Lord’s, offer a novel way in to history.

Five years after the game Taylor painted came the first ‘All India’ tour of England, the subject of Cricket Country(OUP, £25), Prashant Kidambi’s forensic examination of how, he writes, “the idea of India emerged on the cricket pitch in the high noon of empire”. It’s a scholarly work, built on a context wider than the game yet, illuminating how tied to cricket India’s history is.

And if more examples are needed of the game’s ability to inspire the mad and maniacal love that infuses all of these books in one way or another, then the amateur player offers it. First, Neil Cole, his “playing career long since over”, instead recreates Geoffrey Moorhouse’s famous journey through the summer of 1978 in Still The Best Loved Game?(Two Hens Press, £7.99), visiting 18 matches, pro and amateur, during 2018. It’s a gentle undertaking, perhaps a little bogged down in the detail of each game but making the broader point that cricket’s landscape changes like the weather. Moorhouse’s world was one without both the smartphone and the switch hit, and it’s nicely reflected in Cole’s chapter on a village encounter in which the first ball is tanked for four into the trees, and “Buntingford’s opener, Caine, is scoring almost exclusively in boundaries”. Kids today, eh?

That is a landscape deeply familiar to Roger Morgan-Grenville, who has followed up his debut Not Out First Ball with Unlimited Overs: A Season of Mid-Life Cricket (Quiller, £12.95). His only problem is that it’s a landscape deeply familiar to the reader of books in this genre, too, and while he doesn’t break new ground, he and the White Hunter Cricket Club are charming and amiable company for a winter’s afternoon. Schoolteacher and poet Mark Floyer offers a whistle-stop tour around a cricketing life in Chasing Balloons (Charcombe Books, £10). There’s are some rasping phrases here, and jolting honesty, too.