The Adrian Shankar Files, part seven, by Scott Oliver. Part six is available to read here.

This is the final part in a seven-part series. Part six is available to read here.

In The Adrian Shankar Files, a seven-part series, Scott Oliver delves deep into new material about a player who, in May 2011, was fired just 16 days after signing for Worcestershire when it was discovered that his age and the tournaments he claimed to have played in had been fabricated. We will see in detail how Shankar attempted to land an IPL contract with the help of radical bat brand Mongoose, who saw him as the perfect marketing vehicle in their attempts to crack the Indian market, as well as the methods used to secure his Worcestershire deal.

Part seven covers the last embers of Shankar’s attempts to crack professional cricket, and his post-Worcestershire forays into the worlds of filmmaking and charity work.

***

Chip Lambert begins Jonathan Franzen’s international best-selling novel The Corrections as a tenure-track literature professor recently sacked after an improper sexual liaison with a student. He bums around New York for a while, writing a screenplay, and when that is rejected he goes to work in Vilnius for his girlfriend’s estranged husband, an affable though corrupt government official. Chip’s new job involves running bogus websites designed to defraud credulous Americans by duping them into investing in Lithuania’s ‘Free Market Party Company,’ which ostensibly aspires to run “the world’s first for-profit nation-state”.

“The beauty of the Internet was that Chip could publish whole-cloth fabrications without even bothering to check his spelling,” writes Franzen. “Day after day, Chip churned out press releases, make-believe financial statements, earnest tracts arguing the Hegelian inevitability of nakedly commercial politics, gushing eye-witness accounts of Lithuania’s boom-economy-in-the-making, slow-pitch questions in online investment chat rooms, and line-drive-home-run answers. If he got flamed for his lies or his ignorance, he simply moved to another chat room … He felt as if, finally, here in the realm of pure fabrication, he’d found his métier.”

A couple of the career-phases need reversing, and maybe the academic ranking is askew (notwithstanding the unconfirmed part-time Masters in International Relations), but Chip’s trajectory is not too far removed from Adrian Shankar’s, the former Cambridge University student turned cricketing fabulist and later screen-writer and filmmaker. If he got flamed for his lies, he simply moved to another chat room…

Three weeks after what you might be tempted to think of as the ‘shame’ of his ignominious ouster at Worcester, following a week of exorbitant lies to account for previous lies, with MI5, Asian bookies and the ICC Anti-Corruption Unit now part of the story, another Shankar-centric report arrived at Mongoose. Taking into consideration the full context – the extraordinary number of falsehoods that needed shoring up and synthesising, as well as the text’s implicit strategic goal of somehow keeping Marcus Codrington Fernandez batting for him – it is something of a masterpiece of its genre (UTPE/J). Its only real flaw is that, diverging from Johan van Niekerk’s earlier account, it now depicts some of the Impalas team from the Rustenburg T20 as being on the opposition and thus subject to Shankar’s blurring hand speed. But then, to spot such things you would need to have been paying attention to the details rather than being carried along by the button-pushing and string-pulling of those whole-cloth fabrications.

There are more than a few things to unpack here, several immediately obvious questions that might occur to a reader bringing even a modicum of scepticism to the textual encounter. These questions are especially pertinent given that, whether he bought all this or not, Codrington Fernandez would soon be, it would seem, providing hands-on help to bump-start Shankar’s post-cricket career in film.

First, and perhaps most superficially (although it is often the small lies that reveal the most), why would the ambitious Impalas club – backed by one of South Africa’s biggest mining companies, according to Johan van Niekerk – do all this on the hush-hush? Why is there “no fanfare or advertising push” and “no formal PR machine” (Rajkotwala) and yet, previously, the ground was surrounded by “numerous advertising boards” (van Niekerk)? Which is it? Were local companies persuaded to sign up for these advertising boards for “a large crowd of schoolchildren”? These are questions perhaps best put to someone who works in advertising. As Rajkotwala herself acknowledges, “nothing seemed to add up or make sense.”

Second, pace Rajkotwala, the “confusion over his age” was definitively cleared up – chiefly by the police, although a count-back on the chronology would have to have had him going up to Cambridge at 16 years old in order to fit his version of the timeline, not impossible for a maths or physics prodigy, unlikely for a fourth-rate cricketer. Nevertheless, it is interesting to note the way in which the author breezes past it, this fly in the ointment: “What is getting lost among the bile being put forward by the cricketing media is the depth of talent this guy possesses, whether he is 15, 25, or 35.”

Third, Rajkotwala’s oscillating dance between copper-bottomed corroboration and airy insinuation is somewhat curious – now buttressing elements of the story, now creating vagueness and doubt, a he-said, she-said that allow the fictions to live on (perhaps MCF might have benefitted from an exegetical DRS at this juncture). “Truly there is more to this than meets the eye,” she suggests, adding that “the silence from Shankar is telling” (it was, just not in the way imagined by those still unable to see him for the arrant fantasist he was). She neither knows nor cares about his age but seems well informed about everything else – from libel actions threatened by “overly ambitious journalists” and the shutting down of websites (apparently, this can be done by the mere threat of libel), to the ignoring of both positive and complimentary character references and the cricketing opinions of “several respected judges”. And this inside-track (“it has since become known…”) is despite her inability to catch an interview with the “distant and aloof” Shankar as he jumped into the back of a pick-up truck and sped off into the dust to resume his charity work in Botswana, having drilled one of South Africa’s greatest-ever bowlers – previously his Impalas team-mate, Makhaya Ntini – “to all parts of the scenic mountains.”

Distant and aloof. You will recall that on Shankar’s Mongoose ‘Pro Blog’, back in May 2010, he reported being described as “aloof and distant” by “another female,” who we have to presume wasn’t Fatema Rajkotwala, given that she only appears to have encountered him in late October that year – albeit while presumptuously imagining that a “lack of PR machine” meant she could simply “stroll up” up to the star of the tournament for a pow-wow. Perhaps she might have considered approaching Shankar in the three hours or so he would have been sitting around watching the other semi-final, between Warriors and the South African Academy. But then again, we learn that, regardless of whether or not he was hot-footing it across the African savannah and precisely because of that distant and aloof demeanour, “interview requests barely make any headway, which goes some way to explain some of his problems with the media” (yes, some of the way). But then again, there was the fulsome interview he gave to Manchester Evening News when signing for Lancashire, while around the same time he briefly overcame his aloofness to do an impromptu vox-pop for the Independent about his reading preferences.

This media-shy aloofness would perhaps also explain why the post-Worcestershire vacuum of silence was being filled with all these stories denigrating a person Rajkotwala has never spoken to yet feels able to describe – doubtless in conformity with Codrington Fernandez’s own feelings about things – as “likeable and talented” and a “polite and eloquent young man who is widely liked”. Rajkotwala’s desire to divulge more, to push back, is hamstrung by “legal requirements,” which may also of course explain why Shankar pooh-poohed Codrington Fernandez’s suggestion that he grant some fortunate journalist a tell-all interview – “broadcast is better than print (more control, bigger coverage)” – or deploy PR guru Max Clifford, still a few years from his outing as a paedophile. Given all that, the chances of anyone getting to the truth seemed remote. Neither Rajkotwala nor Shankar can make a public statement on the “far bigger story” that is emerging, thereby rebutting the “tragic tabloid journalism” from Cricinfo and The Times (although, of course, Shankar did tell Codrington Fernandez that he had the Financial Times, Evening Standard and Independent ready to follow “their own investigations” with a proper account of things, should he decide he wanted to put his side across).

Fourth, regarding Shankar’s “depth of talent” that was “getting lost among the bile,” who exactly were the “several respected judges” whose views were being suppressed? Professor Ron Goldbeck and Morne Erasmus? As for those “telling references” from “two titans of the modern game,” VVS Laxman was shown pictures of Shankar from 2009 and could not remember ever having met him, let alone seeing him bat, and could anyone really believe that famously taciturn Guyanese legend Shiv Chanderpaul has ever uttered this combination of words: “a rare talent to excite” (as in: I’m looking forward to watching Floyd Reifer bat, he possesses a rare talent to excite)? Perceptively, however, Rajkotwala pinpoints the reason he has continued to fly under the radar: “one of Shankar’s biggest problems is that his most eye catching performances have come away from the glare of the media spotlight and official competition.”

Despite all that, Rajkotwala informs us (and, more importantly, Codrington Fernandez), Shankar was still wanted by Kochi Tuskers Kerala and Chennai Super Kings, with the former’s “abortive attempt to bring him in as a replacement for Mahela Jayawardene towards the end of the tournament” principally stymied by them not having his phone number: “the player could not be contacted for several days and the opportunity passed” (the “opportunity” here being for Kochi, of course). Despite not bidding for him at auction, a “Kochi source” had told Rajkotwala they felt “Shankar ‘belongs in the IPL. The fans will like his style. We have analysed him closely and believe that he can win us matches.’” Perhaps he was more attractive to CSK and KTK now that he could play as a local player, which would be “a major coup” (Shankar had presumably realised he had burnt his county cricket bridges and so registering with the BCCI rather than the ECB was expedient; there was always the chance a county would pick him up as an overseas player, should he go well in IPL5). Given the on- and off-field package he offered – thus far explicitly compared to Jayawardene, Collingwood, Vijay, Kohli, Finch, Hussey, Du Plessis, Buttler, Morgan, Symonds and Tamim, among others – “it is no surprise that Kochi are so keen to add him to their stable,” affirms Rajkotwala. “But the question is – can anyone get hold of him? And if they can, can they quell the anger within?” Ah, the sliding doors of destiny and opportunity: IPL deals missed because your phone battery was dead.

Did Codrington Fernandez believe any of this? Moreover, did Shankar believe it – if not the specifics of the Kochi interest, which even someone as removed from the ordinary run of objective reality as he was would have apprehended, then perhaps the deeper, less detail-bound truth about people in the “lofty circles” of the IPL thinking he could be a “raging success” in the tournament (having scouted him in a quasi-secret competition, “tipped off by their network of contacts to the existence of a league most were unaware of”), both for his “dynamic batting and electric fielding” and the intangibles of his “film-star looks and mystique,” and this despite the “controversy and headlines” that follow this almost totally unknown cricketer about?

While we cannot be sure what Shankar and Codrington Fernandez will have spoken about following their post-Worcestershire email exchange – there is a small clue, however, that Shankar went off-radar (“it is little wonder that there are those in the world who express their frustrations with him”) – what is palpably clear from Rajkotwala’s report is that Shankar has made no confession, and thus there has been no forgiveness required. Rather, he is simply doubling down on all the lies, from his cricketing exploits (Nannes, Afridi, Impalas, Mercantile T20) to how old he was: “Why would an intelligent young man with the world at his feet lie about his age?” Exactly, Fatema. Exactly.

The parallels – albeit of a different order of magnitude and import – with both America’s former narcissist–in–chief and the UK’s prodigiously mendacious Prime Minister should be obvious: if reality doesn’t fit the narrative, simply add more lies (in the words of Trump’s one-time advisor Steve Bannon, speaking about tactical disinformation and fake news, you “flood the zone with shit”). While you’re at it, paint yourself as the victim of these forces of falsehood. If “persecuted Shankar” has been difficult to reach – aloofness notwithstanding, and to the extent that he tragically missed out on replacing Jayawardene at Kochi because of it – then this can only be because “the general consensus is that he is enraged at his treatment by the cricketing fraternity.”

As ever, the functional necessity for Shankar of maintaining the fictions plays on two registers: the strategic (the manipulation of Codrington Fernandez is not entirely gratuitous, and will soon bear dividends for him) and the psychological. Shankar’s narcissistic grandiosity only partly compensates for those nagging inner voices pointing toward his real-world ordinariness, only partly salves the inner wound. This same inner angst also impels him to solicit external validation and admiration: objective sentiments based on false realities, perhaps, but that was not the point. The point was being bathed in the feelings, however unanchored from reality they were. If even one person believed him, there was some solace in that (and Codrington Fernandez was a true believer that Shankar was “the real deal” and “an unmined gem,” ostensibly based on one net with a bowling machine and the clutch of bogus reports). The “whole-cloth fabrications” of his cricketing exploits and subsequent mistreatment kept the admiration flowing, thus ‘corroborating’ Shankar’s inner feelings, and thereby, at the strategic level, kept the cricketing dreams alive (perhaps analogously to the way one might present “sexed-up” sales projection figures in a finance-raise document in order to solicit the ‘external validation’ of funding and so keep your company’s dream’s alive). Shankar knew he had a sympathetic and thus pliable audience in Codrington Fernandez (“it will take an astute CEO and coach to put an arm round him and coax the talent from within”), and it was going to take more than a humiliating sacking for forging passport documents and fabulating achievements in fabricated cricket tournaments for him to walk away from that. After all, there still might be gems to mine.

The solicitous, manipulative, deluded ‘Rajkotwala’ piece – akin to a love letter from an abusive partner – arrived at Mongoose just seven days before the company formally went into administration with debts approaching £600k, at which point the “astute CEO” Shankar was still playing like a fiddle was removed from his post (he was paid a small retainer of a couple of thousand pounds as a brand consultant, although rarely in the office). It paid off, too, if not in a cricket sense. For just as Codrington Fernandez had been advocate-in-chief of Shankar’s IPL push, late in 2012 he helped his young protégé take his first steps into film.

Before then, however, Shankar polished his writing chops. Rajkotwala’s feverish speculations about the “far bigger story” was not his final sockpuppet missive, nor even his last attempt to keep the now odds-against prospects of his IPL dream alive. There was no post-Worcestershire licking of wounds, just a voyage further down the rabbit hole until he ended up in Wonderland as a professional storyteller: Here in the realm of pure fabrication, he had finally found his métier.

In March 2012, a piece by ‘Aaron Nevill’ was sent to Codrington Fernandez’s Mongoose email: ‘Lancashire assess T20 merits of Junaid, McCullum, Shankar’. It was a cursory 270-worder about Peter Moores looking at the county champions’ options ahead of their pre-season trip to Dubai. Apparently, Shankar was under consideration: “[He] left the game in controversial circumstances last summer, but caught the eye of Red Rose overseas batsman Ashwell Prince during a successful recent stint in South Africa” (it was neither recent, a stint, nor real).

Even if it lacked the élan of previous offerings, the appearance of this text further demonstrates that Shankar had not confessed to Codrington Fernandez, and perhaps that he had not yet given up the cricketing ghost. If Codrington Fernandez had ‘forgiven’ him, then, this can only have been a private decision made to himself (assuming he knew they were lies and had simply chosen to overlook it all). The more likely scenario is that, credulous as ever, Codrington Fernandez had swallowed the story about threats from bookies and ACU investigations, about Shankar’s reasons for remaining silent, about journalists motivated by making names for themselves, about “deeper stories,” about Kochi being interested in the persecuted Shankar for IPL5.

Whichever of these is true, he had obviously spotted some storytelling potential in his young and heavingly aspirational protégé. If not in those features by Ramachandran, Conn et al (which he presumably still thought were bona fide), then perhaps in the Mongoose blog trumpeting the “typical dash of élan” he had shown by taking Shankar to a “celebrity haunt”. Or maybe even in a piece Shankar wrote for the Quintessentially website in the summer of 2012, accompanying its editor-in-chief – a contemporary at Queen’s College, Cambridge – to the 5 Pollen Street restaurant owned by Diego Bivero-Volpe, an investment banker turned entrepreneur and writer on “the luxury and lifestyle industries” who is also “passionate about reducing poverty” and has a credit for Made in Chelsea (an episode called ‘Everyone Has Skeletons in Their Closet’). AA Shankar’s review is excruciatingly obsequious, the writerly voice seemingly having mutated from the Boy’s Own Adventures of Norburt and van Niekerk to a sort of cod-chivalric, all at the service of signalling how he belonged in higher social circles – if not in cricket, then somewhere.

Having knocked off the florid edges to his writing in this understated little offering, in October 2012 Shankar co-founded Liberdade Films with Ross Clarke, with whom Codrington Fernandez was working as a producer on the feature film, Dermaphoria, eventually released in 2014. Liberdade was set up for the purpose of making a documentary about footballing icon Socrates, the hard-drinking, chain-smoking doctor who strode imperiously through the Brazilian midfield in the 1982 World Cup and later established a radically democratic structure at his São Paulo club, Corinthians, which snowballed into an oppositional movement widely considered to have been a catalyst for the overthrow of Brazil’s military dictatorship in 1985.

Promotional material for Socrates, which never saw the light of day

Promotional material for Socrates, which never saw the light of day

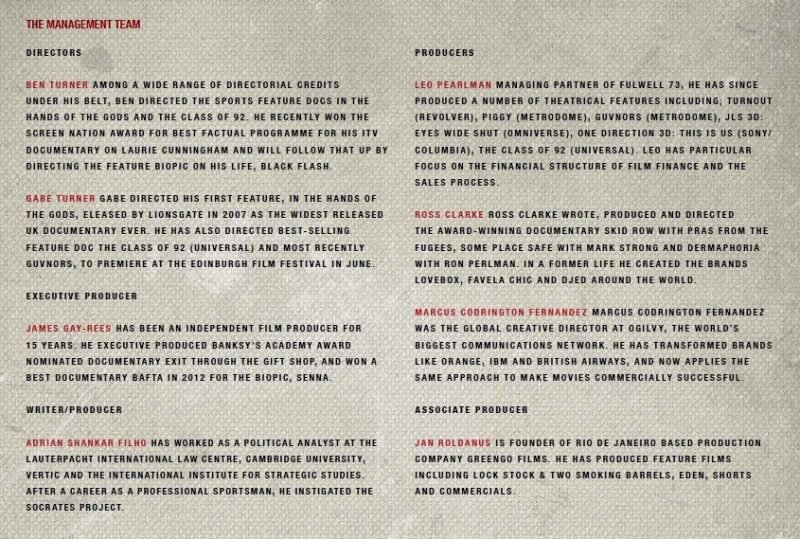

Sócrates had an impressive team behind it. As well as Clarke and Codrington Fernandez as producers, James Gay-Rees was slated as Executive Producer (he had made Banksy’s Exit Through the Gift Shop and would go on to make Amyand Maradona), while brothers Ben and Gabe Turner of Class of ’92 fame were to direct. The scriptwriter was one Adrian Shankar Filho, whose bio in the business plan says he “worked as a political analyst at the Lauterpacht Institute, University of Cambridge, Vertic and the International Institute for Strategic Studies. After a career as a professional sportsman, he instigated the Sócrates project.” (Both Lauterpacht and IISS were asked to confirm whether Shankar had worked there. The latter did not respond, while the former said it could not due to data and privacy laws.)

Although Shankar took the inflation of his CV to unparalleled lengths, practically an art form, it is arguable that everyone exaggerates to one degree or another. Indeed, if we are trying to ascertain why Codrington Fernandez seemed so susceptible to it all, perhaps why they struck up such a friendship, it is worth pointing out that he was introduced by the MC at Mongoose’s IPL launch in March 2010 as having played cricket for England Under-15s (it is hard to imagine that a high-flying creative director left this script to his hosts). His lawyers have subsequently clarified this, saying: “Our client played representative cricket at U-15 level for Headmasters Conference Schools Team and played for his county at U15 level.” Similarly, both the IPL launch and Mongoose’s R3 pitch-deck document presented Codrington Fernandez as “the Global Creative Director” at Ogilvy, a position that does not exist other than for specific accounts. In fact, he was GCD at Ogilvy Action, “the brand activation agency” within the Ogilvy stable, a subsidiary that an Ogilvy official says “was not within the main agency” and which dealt almost exclusively with the British American Tobacco account. A small, though telling misrepresentation. (Codrington Fernandez’s lawyers confirmed: “Our client began at Ogilvy as a creative director on a number of accounts. Within three months he had been promoted to worldwide executive committee member and sole Global Creative Director at Ogilvy Action. That was a promotion negotiated on his arrival at the company.”)

The team behind Socrates

The team behind Socrates

Another interesting parallel here is that, as adults, both Shankar Filho and Codrington Fernandez had spliced their original name with that of their mother. Back in 2000, in an interview with Marketing Week (‘Gullible consumers keep advertising wheel turning’) about Myrtle, the “industry-leading strategic and creative communications company” he had founded between stints at Ogilvy, he was Marcus Fernandez (his mother was née Codrington, and according to friends of the family was a descendant of the slave-owning Codrington family after whom the capital of Barbuda is named).

Anyway, Sócrates never got off the ground. The business plan stated that £135k of its £900k target had been rustled up, with a further £765k to be raised in equity investment. “No filming ever took place,” says Gabe Turner. He cannot recall meeting Shankar in person or how he himself came to be attached to the project, although Turner’s father, David, a leisure and fitness entrepreneur, was CEO of Fitbug between 2004 and 2016, with whom Codrington Fernandez went to work as creative director not long after being ushered out of Mongoose. If Shankar was indeed the instigator of the project – and there is no reason to disbelieve this, given it appeared in a document that would have been seen by his various collaborators – then the likelihood is that he first pitched the idea to Codrington Fernandez (one would have felt Carlos Kaiser to be the more natural story for him to tell) and the latter had then assembled the team.

As we shall see, later snippets place Shankar in Brazil – the country of his mother’s birth – in late 2013 into 2014, although it is unclear whether the list of high-profile interviewees announced in the Sócrates business plan had genuinely signed up. These included former and current presidents Lula da Silva, Fernando Cardoso and Dilma Roussef, footballers Zico, Júnior, Tostão, Rai and Romário, and musicians Gilberto Gil, Caetano Veloso, Chico Buarque and Milton Nascimento. It would be no great surprise to learn that none of them was on board, that Shankar had merely told his collaborators this to build buzz (and had some pre-prepared lie in place should it all go south). If he got flamed for his lies, he simply moved to another chat room…

By the time the Sócrates project was running out of steam, the final (known) cricket report had arrived at post-bankruptcy Mongoose, still settling the debts owed to staff, sponsored pros and suppliers. On January 3, 2013, the day South Africa had bowled out New Zealand for 45 in Cape Town, almost 20 months after Shankar had been sacked by Worcestershire, a South African Press Association bulletin reported on a historic win for Impalas against the Knights franchise, featuring “a beautiful cameo from an overseas recruit, Adrian Shankar, who continued his love affair with Impala with a rapid half century.” Chasing what the uncharacteristically lax SAPA stringer described as a total “pushing up towards 160,” we learn that “a burst of wickets from Du Preez briefly punctured the run rate, but Shankar reversed the slide with a slew of boundaries, pulling Quinton Friend for a monstrous six in the 13th over [emphasis added] before launching into the rest of the attack.” These were, it seems, the final embers.

Before this, however, in May 2012, came news that “a man who is never far from the headlines, on and off the pitch,” was headed to Pakistan to captain a team of Afghan refugees. According to ‘Faisal Farooq’, the Shankar-led team would be taking on “the great and the good of Pakistani cricket” (a tough ask at the best of times, let alone after an extended ostracism from the game). The “series of limited overs matches to showcase new talent” was being organised by one B Rizvi, “a man credited with discovering players like Saqlain Mushtaq and Danish Kaneria.”

The Farooq piece, coming almost a year to the day after his Worcestershire humiliation, indicates a couple of things. First, it shows that Shankar’s post-sacking stories about bookies’ threats of violence and MI5 involvement cannot be solely ascribed to a panicked attempt to salvage his friendship with Codrington Fernandez. This was something more compulsive and pathological in flavour, indicative more of bona fide delusions of grandeur than cold-blooded calculation (after all, Codrington Fernandez was no longer in much of a position to do his bidding, at least not as a cricketer). Perhaps Farooq highlighting Shankar’s “quality of character” and Rizvi’s “complete faith in him” was a nudge for the Sócrates project.

Either way, the allusion to the murkiness (“he has suffered because he would not accept help and advice from cricket people”) gives us some clue as to how Shankar had resolved the Worcestershire narrative for Codrington Fernandez’s benefit: taking the bullet of public disgrace as the lesser of two evils (it would seem that police in Colombo, Mumbai and Worcester had been unable to find the smoking gun). This gave both parties a convenient narrative ‘out’. Yes, the Sri Lankan tournament had happened, it was just that, as Rajkotwala had described, “the statistics have not been made official as it was a private league conducted against the authority of the SLC Board.” The truth would never come out (unless, perhaps, a journalist had the radical idea of speaking to other cricketers in the Mercantile League or the Sri Lankan board). It would remain a cross Shankar had to bear, another tool with which to manipulate the emotions of others, emotions with no basis in real events but which were nonetheless sincerely expressed and gratefully received.

The second notable aspect of the Farooq piece is that it marks Shankar’s pivot to working with refugees and, more broadly, to progressive politics. These may be his genuine political sympathies, although even these charitable sallies are streaked with his characteristic grandiosity, his desire to turn it all into a means of projecting his specialness and importance, and thus, perhaps, were at bottom just another means to cultivate the admiration of others. Asked in 2017 whether he felt he had been manipulated by Shankar, Codrington Fernandez said: “The remarkable work that he has done for a range of charities over the past five years also backs up my view that he is deserving of support, then as now.” This is, essentially, the Jimmy Savile defence. Everyone deserves the right to second and third chances in life, of course, a shot at redemption, but this has to be accompanied by a sense of responsibility for one’s actions, perhaps for contrition, a taking ownership and mending of ways. There is ample evidence that none of this happened, that Shankar is simply unable to help himself from spouting lies both spontaneous and calculating, his way of navigating life’s ever-unfurling complexity.

According to a colleague of Shankar’s on the Cricket Without Boundaries trip to Botswana in October 2010 – interrupted by his Impalas adventure in Rustenberg and eventually finishing early, perhaps in order to attend the ‘Mind the Windows, Banger’ shoot – his first contact with CWB had come on June 8, 2009. He sent an email outlining that he was a Lancashire cricketer interested in getting involved, citing a number of his other charitable involvements. Subsequent contact largely concerned promises of appearances by James Anderson, Andrew Flintoff and Mal Loye at CWB events, none of which materialised.

In February 2019, in a 49-minute interview with aspiring actor and wellness YouTuber Monica Wadwa on the Love Talkin’ podcast, Shankar discussed time he had apparently spent filming in ‘the Jungle’ refugee camp in Calais. On at least one visit to Calais that we can corroborate, he was there with a charity, which has asked to remain anonymous. Their recollection of Shankar is that he “seemed to very quickly go from ‘friendly volunteer’ to ‘chap who desperately wanted to make a name for himself by filming refugees and taking too many photos’ and […] wanting to introduce us to some big industry names of cinema and human rights work.” Interestingly, in the middle of the interview, Shankar mentions the etiquette or taboo around taking identifiable photos of refugees, citing a Daily Mail reporter who had been in Calais doing exactly that. Given his history of using Codrington Fernandez as the means for his own fevered ambitions, it would be reasonable to assume he initially struggled with the competing demands of furthering his own filmmaking interests and respecting the needs of these vulnerable people.

Wadwa introduces her guest as “such a compassionate, empathetic and amazingly cultured person,” traits that certainly shone through in his 2010 Mongoose ‘Pro Blog’, written at the age of 28. “We are scheduled for a week in Geordieland now,” he reported, “so next week’s blog should include details of a pastry eating contest at Gregg’s.” This is the compassionate Shankar who wrote: “We headed to Grimsby, aka the suicide capital of the North. The suicide rate is sky high there as it is comfortably the most interesting thing to do in the area.” The same empathetic Shankar who described a jaunt to Colwyn Bay thus: “A couple were ending their friendship by getting married, and as we walked into the hotel lobby we were treated to the unusual sight of a 16-stone bride in a white dress and black thigh high boots, stumbling around and knocking plants over.”

Shankar’s account of how he came to (help) make a film whose title remains unnamed through the interview is that he was “introduced by a friend of mine” to a documentary maker who had followed two Iraqi brothers and a Syrian mother and her two children all the way from Turkey through Europe. When they reached Calais, the friend-of-a-friend was set to catch up with them. “I said I’d love to go, first of all because of that desire to make something… That’s how that section of my work started.”

There was a potential glitch, however. A couple of days before they were due to head to Calais, the Bataclan terrorist attack happened. As events unfolded, Shankar was exchanging messages with “a friend of mine” who was in a nearby theatre, telling her to stay put. When they got there, the visit to the Jungle was an eye-opener: “A really good friend of mine from university was editor of the Independent at the time. Amol Rajan, who’s now the BBC Media Editor. A very successful guy. I messaged him when I got to Calais: ‘It’s like a warzone’. He messaged back: ‘Tell me more!’” (The Independent’s correspondent Joseph Charlton had spent three days inside the Jungle two months before Bataclan.)

Shankar says he/they made two films in Calais – the second at the end of 2016 when the camp was dismantled – and, on a couple of occasions, Wadwa uses the phrase, “watching your documentary…” The documentaries may well exist somewhere in some form, but there is no online record of a film both fitting this description and for which Shankar is credited (this is not necessarily unusual).

Wadwa had met Shankar at the 2018 Cannes Film Festival, and most of her questions cite earlier conversations between the two, things that he would have spoken about in a less formal context. Midway through the interview, she pivots to the role of art in “changing attitudes towards compassion,” then asks why Shankar had “moved away from documentaries and started to make fictional projects. You mentioned that was because you got yourself into some quite dangerous situations.” He replies, “I probably won’t go into specifics…” before explaining, without missing a beat, that he didn’t wish to add any fuel to the atmosphere of demonisation of refugees. He then references Werner Herzog’s remark about documentarists being “the soldiers of film-making” (it seems especially odd in this light that no-one documented Shankar’s 152 from 121 balls in front of 10,000 fans in the heat of Jaffna). And he pays homage to the on-the-ground, front-line heroes delivering practical help.

We should not be too harsh in our judgement. It is perfectly possible that Shankar had a Road-to-Damascus moment, metaphorically speaking, that all this emoting was perfectly sincere and he was focused on adding good to the world, maybe that he saw it as a form of atonement. It could also be true – at one and the same time – that he intuited it as an opportunity for self-serving ‘performative compassion’, for personal reputation laundering. Compassionate acts, true, but not felt as compassionate, only understood that they are perceived that way and thus that there is a dividend of social cachet to be gleaned.

These are distant events and incredibly murky psychological waters to peer into, but the track record is not in this particular leopard’s favour. Shankar has shown a remarkable adroitness at context-sensitive self-aggrandisement. As he wrote to Codrington Fernandez seven days after his Worcestershire exit, “It’s ironic that I am being accused of boasting and bragging my way into certain positions when I never made a single boast in the blogs or on Twitter. You would think someone would have noticed that it does not add up.” Of course, the boasting on the Mongoose blog was oblique and non-specific (“after a sizeable contribution with the bat”) only because of the constraints of public verification. The corpus of post-truth UTPEs were different. Codrington Fernandez may have believed them to be in the public domain, but they were private communications primarily designed to manipulate him (and to service Shankar’s need for admiration). There were no real constraints. Indeed, as Shankar says to Wadwa, paraphrasing the writer James Baldwin and apropos his ‘art’ as a documentarist: “An artist is like a lover. You have to open up the eyes of the other person and make them see what they couldn’t see before.” It is perhaps the best description of the artistry that went into that oeuvre – Norburt, van Niekerk, Hunter, Ramachandran, Erasmus, Conn, Singh, Pandani, Wiseman, Goldbeck, ‘a Lancashire fan’, Rajkotwala, Farooq – all of them with a principal audience of one man, allowing him to see what he couldn’t see before: Adrian wielding the Mongoose, savaging the short ball, darling of the Indian crowds (but only if an astute CEO can put his arm round him).

The copious written output may not have helped get Shankar into the IPL but it left an impression of him in Codrington Fernandez’s mind as a gun cricketer, an impression that managed, with a little ancillary finessing, to survive public exposure as a fraud who had invoked make-believe tournaments to win a contract. Perhaps the fact that Shankar had to take it all on the chin won him even more admiration. Anyway, one door closes and another one opens, and Shankar had his leg-up into film.

As previously noted, blagging it as a sportsman is impossible, precisely because of its brutally objective measure of aptitude. As a filmmaker, you could in theory blag your way in with a baseline level technical competence, learn on the job, and who would later care too much if you had embellished your credentials a little, provided your work now was up to scratch? More generally, ours is not an age devoid of opportunities for vendors of snake oil. On the one hand, there is internalised hyper-competition, at both an individual and institutional level. On the other, there is the attendant mania for self-improvement (as opposed to modifying the ecosystem of our political economy), for performance enhancement and marginal gains, to be Fitter Happier workers and citizens. There are a whole raft of industries – a post-modern syncretism of managerialism and mindfulness – able to surf the post-modern anxieties, the space where affluence (or disposable surplus) meets credulous neediness. Not much use in a pandemic, but high yield. A little eloquence and believability go a long way.

Anyway, after having led Mongoose to bankruptcy inside 25 months, Codrington Fernandez has largely returned to his old beat, starting at Fitbug. Since 2015, he has been a director at Super Future Cambridge, where he is a “leadership coach for people in business, government and sport.” He is also a trustee of the Foundation Years Action Group: “the cross-party group – chaired by Frank Field MP – promotes the vital importance of the first three years to children’s development and life outcomes to government and policy makers.” The obvious question there is: if you spent the first three years in a coma and the WHO said it didn’t count toward your age, would that make you more likely to invent fictitious cricket matches in an attempt to inveigle your way to professional contracts?

Alongside this, he works as a freelance ‘Creative Strategy Director’ at Cambridge-based communications company CPL. Outlining their ‘Content Strategy’, CPL say they create “messaging houses, content roadmaps and story schedules that consider multiple channels and audiences and help you organise your storytelling for maximum effect. Your content strategy needs to work hand-in-hand with your wider business, marketing and communications plans to ensure you’re telling a consistent story to your clients, customers, members and employees.” What happens if your story is so consistent that attempts to write in the voice of multiple journalists from a variety of cultural backgrounds ends up becoming too homogeneous, drawing on the same diction and syntax, the exact same grammatical and typographical quirks (no hyphenation of compound adjectives, all double-spaced at the end of sentences)? Is that the sort of thing that would be picked up?

By the time Shankar appeared on the Love Talkin’ podcast, his storytelling ability further honed, he was working for Five Fifty Five films, a small production company in Soho founded by Kate Baxter, who had worked with Ross Clarke. Shankar had not only appended Filho to his surname (one of the rare occasions he did use a hyphen) but also added an accent to Adrian. His company bio read: “Adrián Shankar-Filho is a filmmaker having joined Five Fifty Five in 2018 and is now running development on over 5 series and feature films. Having made over 20 short films and music videos, starting out by capturing the mass protests in Brazil in 2013-14, Adrian spent years working and filming in refugee camps from Dunkirk and Calais to Paris and Belgrade and further on to Greece, Lebanon and Jordan.”

It had been quite a journey, again metaphorically speaking, from ‘first appearing on the radar’ at Cambridge with his Varsity hundred and assault on Shahid Afridi, through the mysterious fourth year of university cricket, the three-year gap playing for Bedfordshire and Spencer CC in and around an 18-month bout of glandular fever, the hundreds for Kent IIs, the two-year deal at Lancashire on the back of 104 runs in four trial games, the departure from Lancashire to be closer to his family, the trip to Botswana where he nipped across to Rustenburg to play with/against Makhaya Ntini, the on-set meeting with ‘Tres’, the registration for the IPL auction, the non-attendance of a Rajasthan trial, the plotting and writing and dreaming on his Sri Lanka jaunt, with its man of the tournament award, off-grid 152 in front of 10,000 supporters and no press in Jaffna, and then the domination of the Mercantile T20 League, which opened the door for the Worcestershire episode, with its live TV appearance, knee injury and ad hoc website, after which came the revelations about threats from bookies and co-operating with the ACU and MI5, the ‘sometime gastronome’ interlude, working for the Lauterpacht Institute and International Institute of Strategic Studies think tank at some point, then Liberdade Films and sourcing interviews with three Brazillian presidents and several world-famous musicians and footballers, and finally the work about refugees, the work with the homeless (“half an hour on a Friday afternoon”).

By late 2017, when not playing 5–a–side football at William Tyndale School in Islington, Shankar appears to be working for xACTLY films, an adjunct of Kikit Entertainment, whose owner, Kiran Sharma – British born, Indian heritage, from Bedford, successful father – may or may not have been an old friend of Shankar’s, but did appear to know Kate Baxter. Sharma had been manager of Prince – as in, Prince Rogers Nelson – for ten years until his death in April 2016, but in the winter of 2017, with Shankar in tow and taking photos of an icy Minneapolis, Sharma visited America to hook up with Prince’s band, the New Power Generation.

The following year came Shankar’s debut IMDB-credited work, as first assistant director on Red Crayon, a short whose executive producer was “the very distinguished figure” of Diego Bivero-Volpe, previously seen “brimming with charisma and foppish hair” at 5 Pollen Street, down an aloof side street in Mayfair. The film was written by and starred Bivero-Volpe’s wife, Charlotte C Carroll. Bivero-Volpe was also a friend of the Forbes and Vanity Fair lifestyle journalist Bridget Arsenault, who was also a producer on Five Fifty Five’s short film, Whirlpool (via her Long Winded Lady Productions) and hosted an event with Shankar, a friend, who was himself a “kind supporter” of Bivero-Volpe’s charity parties at Mayfair’s Black Roe Poke and Grill. A tight circle.

By May 2018, Shankar was Shankar-Filho and in Cannes with Five Fifty Five (the festival’s closing film that year was Terry Gilliam’s The Man Who Killed Don Quixote), meeting Monica Wadwa and networking, the natural element for “a polite and eloquent young man” (Rajkotwala) who is “thoroughly charming” (Codrington Fernandez). He may or may not have been talking about his “over 20 short films and music videos,” which encompassed “capturing the mass protests in Brazil” through the “years working and filming in refugee camps.”

Given Shankar’s copious track record of falsifying his achievements – that is, of completely inventing them – it seemed reasonable to doubt the veracity of this Five Fifty Five bio, reasonable to enquire whether they had checked it out and could confirm the claims.

Founder and boss Kate Baxter was asked in February 2019 whether she had done just that, whether Shankar-Filho had provided references. “Oh yeah, loads. I have several references from other filmmakers and other film companies he’s worked with, including Working Title, including Oscar directors – like, all sorts.” Working Title made Pride and Prejudice, Billy Elliot, Captain Corelli’s Mandolin, the Bridget Jones films, the Johnny English films, Hot Fuzz, Shaun of the Dead, Four Weddings and a Funeral, Notting Hill and Love Actually, among many others. They made most of the Coen Brothers’ films. It is not clear in what capacity Shankar worked for them, although they did also make the documentary Senna, whose executive producer was James Gay-Rees.

Shankar and Baxter at Cannes

Shankar and Baxter at Cannes

Regarding the “over 20 short films and music videos”, Baxter said: “The wording is very carefully chosen there [on the company profile] – which it says he’s ‘connected to’. So he’s been supporting, or been a piece of one of the – …a crew member or somebody working on that number of films. And, I don’t know if it’s exactly twenty, but I’m aware of about fifteen.”

But of course, this is precisely not how it was worded, notwithstanding the pliability of the verb “made”.

Baxter went on to explain: “I probably get two or three news links from him on an every-other-day kind of basis. And they’re from proper news sites, which may or may not be partially fake news because who knows these days. But they’re definitely not fabricated by him. You know when you’re on a website and it says ‘share this with’ and then you can share it in an email? That’s the kind of link I get. And it’s all related to what he’s working on.” This sounds familiar. An exhaustive search threw up no features related to Shankar-Filho’s work on various film projects.

Specifically about the music videos, Baxter said: “He does that [make music videos] for his friends all the time. His Instagram shows that he is always working on a new small music video. Those are the kinds of things that, as a filmmaker, you don’t want anyone to see. So you don’t link them online because … because a lot of times the artist is choosing one that they want and you just have to go with it. And it doesn’t reflect on the kind of quality or content that you want to make.”

The logic here is hard to follow. If you had made a music video that was rejected by the artist but with which you were happy, the act of rejection would have no bearing on whether you included on a show-reel or other such portfolio of your work (“I made a good video; the artist rejected it”). Unless of course what is meant here are the types of fan videos you see on YouTube, usually an audio track backed with stock footage. Does this count as ‘making a music video’?

Specifically about the refugee camps, Baxter said: “I don’t know if he was physically in all those places. But he was working in films that were made in all of those places.” Suffice to say that doing post-production work on films made by other people in other countries is quite clearly a different claim than “Adrian spent years working and filming in refugee camps.” In the Wadwa interview, Shankar mentions going to camps in Belgrade in early 2017 and talks about “much better conditions in camps in Lebanon, Syria and Jordan,” using the ambiguous phrase “if you go to [those places]” rather than the more definitive, “when I was in the refugee camps.”

None of Baxter’s explanations give the impression of a person who has learned their lessons and changed their ways. To repeat, everyone deserves a shot at redemption, but true change always requires a moment of contrition and reckoning, taking ownership of past decisions and mistakes. In Wadwa’s words: “I want to help others, through open & honest conversation & sharing, to FIND THEIR LIGHT & allow their truth to SHINE in alignment with their everyday lives. Subscribe to my channel and follow my Instagram @monica.wadwa for my journey, with tips, advice & insights, & together we can reconnect back to our Truth.” Wadwa did not respond to multiple requests regarding whether she had seen Shankar credited on the purported documentaries of his she had watched, so that is one open and honest conversation endeavouring to reconnect to truth that has gone begging.

Regarding how familiar she was with Shankar’s past missteps in the sphere of truth-telling, Baxter said: “When I approached him about [the cricket story], he was like, ‘Yeah, I lied. There was a lot of pressure at the time’.” It is unclear to which part of the lie-heavy 2004 to 2011 period this “pressure” refers. Earlier, Baxter had observed: “Adrian’s not always a trustworthy character. He’s just not.”

Which makes it all the more strange that Baxter was not prepared to verify his filmmaking credentials. If the filmography and experience were true, it would be easy to share that information. Depending on your definition of a film – and we live in an age in which people can ‘make a film’ on their phone by pointing it at their mate doing a skateboarding trick – it may well be correct that Shankar-Filho had made 20 films. If he had, it is difficult to understand why it was not in their interests to provide evidence for it. Baxter would only say, “That’s not my job [to verify the 20 films]. You can ask him.” (Shankar refused multiple requests for comment.)

Instead, Baxter said she was “wary of sharing materials,” despite this being a simple case of verifying what was claimed on the public face of Five Fifty Five, her company. “I have definitely seen fifteen of them,” she added. “They are on his Instagram.” She then indicated she was going to look into things. However, curiously, within half an hour Shankar’s Instagram, @theballadoftoninho, had been switched from public to locked (it did contain phone footage of him playing a ‘tweener’ at the Cumberland Tennis Club in Hampstead, so that was another one to add).

In late 2019, Shankar-Filho was no longer working with Five Fifty Five. His name had been removed as director on Hell Fighter, a film about a jazz pioneer who fought in a predominantly black unit of the US Army, a project for which Shankar had interviewed former Secretary of State, Colin Powell. ‘Shankar’ is not even a keyword on Colin Powell’s page on the project. Kate Baxter did not respond to multiple attempts to ascertain why this erasure had happened.

Adrian Shankar-Filho interviewing Colin Powell

Adrian Shankar-Filho interviewing Colin Powell

Subsequently, Shankar has continued in filmmaking. He was involved in Nobody’s Listening, a VR Project raising awarness about the Yazidi genocide in northern Iraq. He directed a documentary, Mother, in 2020, the story of two child refugees who crossed the world (filmed in Hastings), and the short drama Lockdown Love Part One this year. He has continued his charitable work, too, appearing alongside Kiran Sharma on the Arms Around the Child Committee (where he is listed as part of xACTLY films) for an impressive and worthy art auction slated for Friday 13 March last year but postponed amid the early stages of the pandemic. Running proceedings would have been Hugh Edmeades, who took over as IPL auctioneer in 2019 (a conversation starter, then). The struggle is not to identify a good path through life. It is to walk it on your own merits, with achievements unalloyed, with limitations overcome through effort rather than deception, doors opened primarily through honest labour (and, yes, for many, through well-connected advocates). Success should be earned and admiration should be prompted by real not make-believe accomplishments.

Speaking of success, at the end of the Wadwa interview she throws him a few softballs. After being asked for his definition of love (“the most powerful force in the universe that we’re capable of”) and then of happiness (“a sort of tranquillity”), he’s asked for his definition of success. “That’s tricky,” he begins, trying to find the right words, weighing things up. “I guess, literally, someone sets themselves a goal, ‘I need to pass this exam’, and they do. Success to me feels like a communal thing. If you have an individual piece of success – you win an award or something like that – it’s great and you’re happy for that moment but when you do something that has a positive effect on a large number of people and they can share in that success, that feels like something more real and tangible. That individual moment of success doesn’t resonate too much with me.” Indeed, as Professor Ron Goldbeck had written, the important thing about Shankar’s assault on Afridi was “the delight of his college friends, dancing around with their Pimms in hand,” all sharing in his success. The innings as gift.

Wadwa then asks him what “the world needs more of” in his view. “Part of me wants to say education,” he replies, “but a bigger part of me wants to say compassion.” It is a good and worthy answer – indeed, it is difficult to imagine an answer that was more contextually advantageous to the personal brand, one that would go down better with a wellness vlogger – but it is also perhaps arguable that honesty, truth and accountability have their merits.

“The individualism that has been the predominant ideology for a long time now is having serious consequences,” Shankar goes on, with a combination of film-star looks and mystique that the Indian public thrives on. If there is a dinner-party shallowness to this assertion – one that presumably would have been fleshed out in a paper for the International Institute for Strategic Studies – then one can only remark that the world is a complex and difficult place to navigate, that it is hard to join the dots, even more so while moving in social circles whose business is pushing hyper-aspirational leisure experiences while simultaneously being invested in bien pensant benevolence. Networking among Kensington and Chelsea’s philanthropic guardians of the status quo, saving the world one party at a time, is likely to create ideological interference patterns.

Finally, Wadwa asks the big one: “What is the greatest life lesson you’ve learned?” He takes a beat, then says: “Every moment of my life that I regret is when my behaviour or actions have fallen short of standards, and that’s had a negative impact on people. I regret all those moments and wish I could go back and change those. I at least try now to behave and act in a way that hopefully has a positive impact, whether that’s through work or your personal life. Sometimes that’s difficult, because in the heat of the moment a bad decision you make negatively impacts people and maybe yourself.”

There were many people negatively impacted by Shankar’s behaviour. The damage to Codrington Fernandez’s reputation was largely hidden until his full-throttle IPL advocacy became public, and who knows quite how things have ended up there with regard to the post-Worcestershire spy-novel explanations, that heat of the moment that had Shankar sending in reports about IPL interest 20 months after being outed. Self-deception about your talents is one thing, deception of others something else. Some good people became collateral damage in all this, unable to speak about it ten years on. Worcestershire was not a momentary aberration, but the apogee of behaviour that pre-dated it and, it seems, has not been entirely extirpated.

Just as the fake news reports and sockpuppet emails were an indirect way of communicating with and ascertaining the views of his advocate-in-chief at Mongoose (“I wanted to ask you about a player of yours”), so this answer feels like a way of shoring up the narrative of his post-cricket penitence for the benefit of his then boss, Kate Baxter. A more experienced interviewer than Wadwa – even without any familiarity with his back-story – might have asked him to be more specific, to commit some flesh to the platitudinous bones. For instance, she might have asked: “Can you give us an example of one of those moments when your actions ‘fell short of standards’ and ‘negatively impacted people’?” Instead, she signs off with, “You’re so modest about everything you do for other people. You’re such a silent soldier.” Thoroughly charming. Job done. If he got flamed for his lies, he simply moved to another chat room…

And what better arena than film to move to? He felt as if, finally, here in the realm of pure fabrication, he’d found his métier.