There are four stages to Stuart Broad’s career. The period when he first entered the side; the Andy Flower years; the years of Broad and Anderson running the attack; and ‘Late-Broad’. This is the story of how Stuart Broad took 500 Test wickets.

Phase one: Wild Thing (2007-09)

It feels odd to say it, but when Stuart Broad made his Test debut way back in December 2007, people weren’t quite sure what to make of him.

When first making his way in England colours, Broad was far from the line and length merchant he would later become. Like many of us, in a new situation where we don’t quite know our place, we’re willing to adapt in order to fit in. With other more senior teammates trusted to take the new ball – James Anderson, Ryan Sidebottom, Steve Harmison – Broad was used in a variety of different roles.

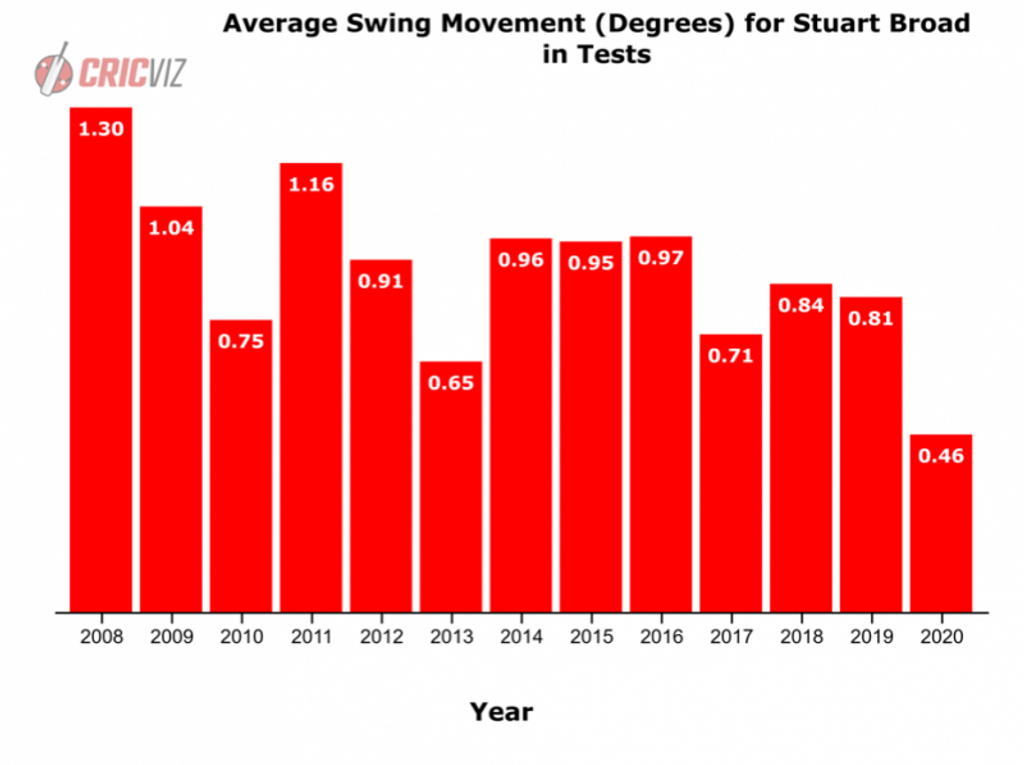

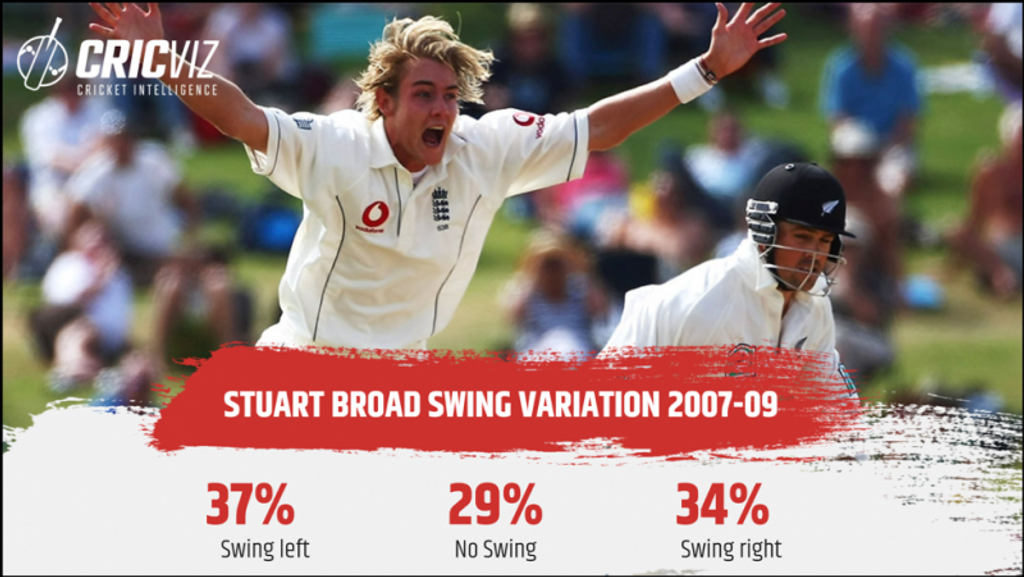

In those early Tests, he was bowling a bouncer roughly once an over, even though he wasn’t express pace, he was occasionally deployed as a sort of back-up enforcer. He had an outswinger to the right-hander (42 per cent of his deliveries swung away, more than Anderson), but also had the inswinger (31 per cent of deliveries), and could be used accordingly. In that first full year of Test cricket, Broad averaged 1.3° of swing; he’s never found more in the subsequent 12 years.

At the start of his international career, Broad had all the raw tools to be whatever kind of bowler he wanted. The ability to swing the ball, and bowl bouncers, made him a very malleable, versatile talent.

He had issues, like any young bowler. He struggled to blend his movement with accuracy, and in those first 12 months of Test cricket just 29 per cent of his deliveries were pitched on a good line and length, a figure trumped by Matthew Hoggard, Sidebottom, Andrew Flintoff, and Darren Pattinson – the only England seamers with lower ‘accuracy’ were Anderson and Harmison, both a good five kph quicker than Broad.

Oddly, in the early days when Broad was bowling those bouncers and wildly swinging the ball in every direction, pundits were predicting Broad would master this aspect of bowling. An article from Simon Hughes in the Telegraph, published the day after Broad’s match-winning spell at the Oval in the 2009 Ashes, proposed that the youngster had followed ‘The McGrath method’, and it was a popular reference point at the time.

Yet that spell, the first of the classic Broad devastations, didn’t quite fit the argument. 46 per cent of the balls he bowled in that spell were short, and while three of the wickets came with pitch up balls, this was no metronome. It may have been the plan for the future, but Anderson, Flintoff, and Graham Onions were all more accurate that series. At this point in his career, there was an odd disparity between the bowler Broad was, and the bowler people thought he would become.

Perhaps this early identity crisis was just Broad as a victim of circumstance. In his first 11 Tests, Broad was captained by three different men; Michael Vaughan, Kevin Pietersen, and Andrew Strauss. The strategic differences between these men hardly needs to be spellt out, nor the well-documented power struggles behind the scenes. Perhaps it’s no surprise that Broad’s role in the attack was not crystal clear until the Andy Flower era kicked fully into gear, during the winter following the 2009 Ashes.

In that era, things would change dramatically. For different reasons, England were shedding the flair talents of Ravi Bopara and Flintoff, and embracing a streamlined, efficient approach. Faced with the opportunity for a romantic return for Mark Ramprakash at the Oval for that decisive final Test, Flower went with the ultra-solid Jonathan Trott instead, a decision vindicated by both the result and the following four years of world-class run scoring. An era of reigning in, of talent being maximised and efficiency being prized, was in the offing. Broad would be no different.

Phase two: The Andy Flower Years (2010-13)

Under Flower, Broad blossomed. “I hold Andy Flower in the very highest regard as a coach and as a man”, Broad wrote in his second autobiography, Broadside. It’s easy to see why, given how their successes entwined.

After the 2009 Ashes, and in the years that followed, Broad found a tactical and technical certainty which took his game to the next level. For the rest of Flower’s tenure, Broad took the new ball in 74 of the 87 innings, that iconic partnership of Broad and Anderson became the backbone of attack. Broad’s role was clarified; he was the new ball bowler.

The central tenets of Flower’s plan were batting time, and bowling dry. While Alastair Cook, Strauss and Jonathan Trott took care of the former, the latter fell largely on the heads of Broad and Anderson. “Bowling dry” was, essentially, about limiting runs, and particularly boundaries. The aim was to force batsmen into injudicious shots, taking wickets through cumulative pressure, rather than bowling ‘magic-balls’.

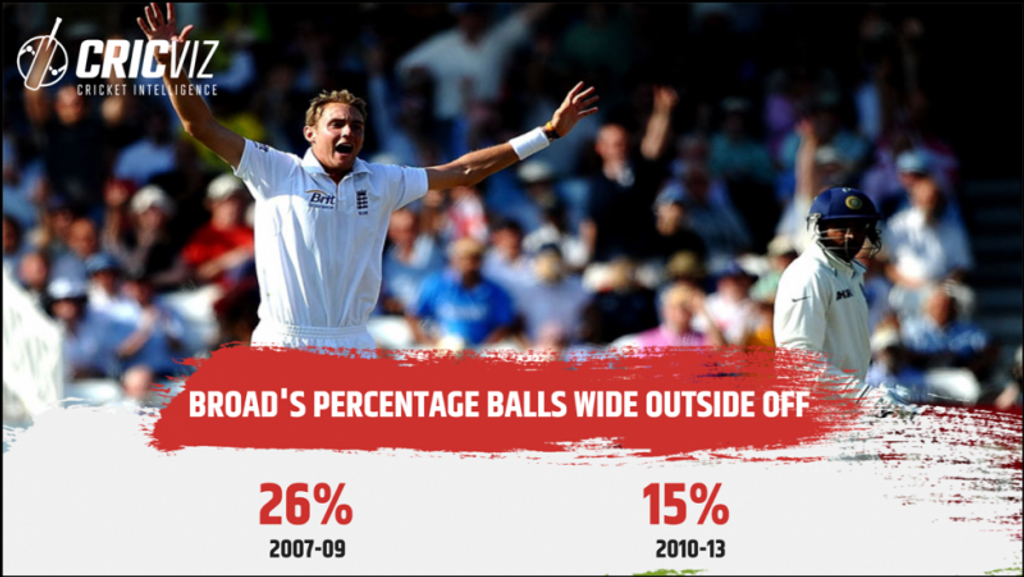

Broad fell into line. He began to bowl a lot straighter; having previously sent down a quarter of his deliveries well wide of off stump, he reduced that to 15 per cent. With this emphasis on building pressure, accuracy became the main feature of Broad’s bowling. That ideal zone for the Test seamer, on a good length just outside off, was his home. In this part of his career, 29 per cent of Broad’s bowling was on a good line and length; from 2011 through to 2014, it was 40 per cent.

His economy rate fell from 3.2 to 2.8 runs per over, bowling more maidens than previously, his control improving all the time. To an extent, the natural progression of a maturing seamer; in part a tactical choice, the player responding to the needs of the team.

It all made a huge difference to his overall effectiveness, and his bowling average tumbled from 36 in that initial phase to 28 for the next four-and-a-half years. During these years, Broad was indisputably one the best bowlers in the world.

In this period, England’s high point was probably the 2010/11 Ashes win, but Broad’s on-field role was minimal. Forced home through injury after the second Test, he missed out on the era-defining wins at Melbourne and Sydney. Showing pictures to the grandchildren, Broad might flick past his own figures rather quickly – two wickets at 81 is not the contribution he’d have wanted in that team’s finest hour, his worst ever average in a Test series.

It’s fitting then, that Broad’s own peak came during a low for the team as a whole. In 2012, England went to the UAE, and were whitewashed 3-0, a major blot on their record – but Broad bowled superbly. He took 13 wickets at 20.46, in a series when all the other seamers averaged over 31. His secret was clear; 55 per cent of his deliveries were cutters, as were almost all of his wickets. Adapting his approach, and moving away from the classic approach of the English seamer, resulted in one of the great English seam performances in Asia – though it would come at a cost.

Phase three – Stuart Broad and James Anderson in control (2014-2017)

The Flower era was defined by personal sacrifice and collective success, and for England, the years following his departure as coach were a struggle to regain identity. That 2013/14 Ashes debacle kickstarted a cycle of difficult overseas tours, reaching a low with a 13-Test streak without a win away from home. The retirements of Pietersen, Trott, Graeme Swann and Matt Prior hit England hard.

Alongside Cook, Broad and Anderson stood as the survivors of the glory period. With the arrival of first Peter Moores and then Trevor Bayliss, neither of whom exerted the same tactical control as Flower, Broad and Anderson stood in a more dominant position within the dressing room. With that position, came control and autonomy.

In 2014, the first summer without Flower, Broad and Anderson bowled very short with the new ball. Their average opening spells pitched 7.4m from the stumps, by far the shortest they have recorded in a home season. Even without the General, the plans were still being followed, perhaps even more so than before. That summer, perhaps coincidentally, Broad and Anderson recored their the worst ever strike-rates with their opening spells in a home summer.

Perhaps it was another coincidence that the following summer, 2015, was the fullest Broad and Anderson had ever bowled with the new ball in England, and their second best strike-rate. This little reversal tells the tale of the era for Broad. In the absence of the strict tactical framework of Flower, there was greater responsibility seemingly placed on England’s senior bowlers to dictate the pattern of play. At times they got it right; at times they got it wrong. Regardless, Broad began to innovate with his own game.

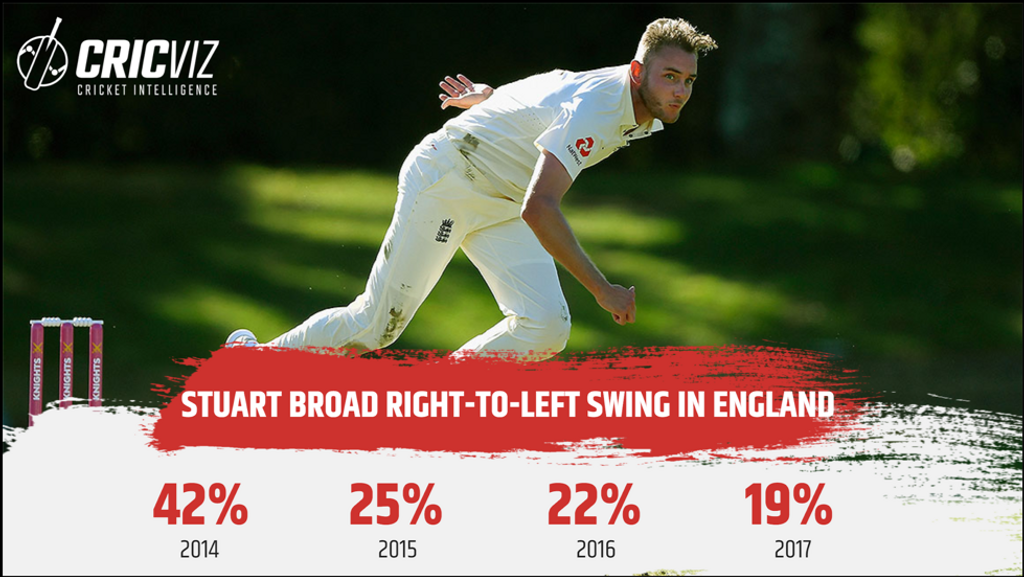

Another crucial factor forcing Broad in this direction was a series of technical issues, and physical discomfort. Much was made of the fact that, around 2016, Broad was ‘losing his outswinger’ to the right-hander – and the data backs it up. Broad’s overall swing movement was staying roughly the same throughout these years, but he was finding it much tougher to move the ball from right-to-left, the outswinger to right-handers or the inswinger to left-handers.

Many astute observers have suggested that when bowling all those cutters in the UAE, Broad lost the wrist position needed to swing the ball in such a way. When changing your grip so fundamentally in order to get that side spin on the ball, it’s only natural that the repetitive nature of presenting the seam might suffer.

Broad has since said that around this time: “We had a Test match team of Cook, Lyth, Stokes, Moeen – so I was bowling at left-handers constantly, and what I didn’t do was maintain or repair good habits against right-handers, and I felt like I lost my action on the right-hander front.”

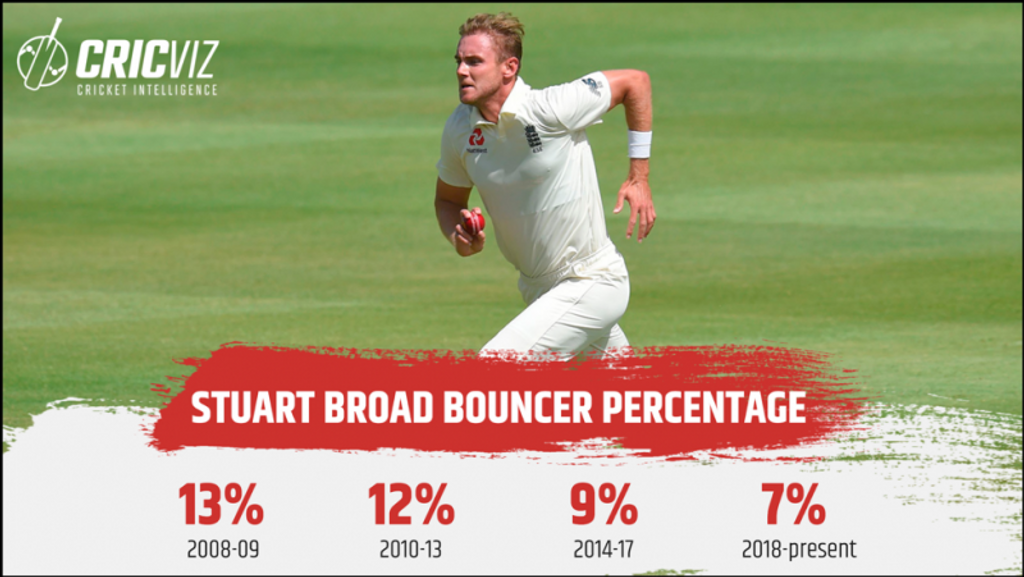

Around this period, Broad also started to significantly reduce the number of bouncers he bowled. Broad may have only been in his late-20s, but he had played a huge amount of cricket; in the decade after his Test debut, only Anderson bowled more deliveries in international cricket than Broad. He talks in his autobiography of the huge swellings on his knee that plagued that 2014 summer; the raw physicality of Broad’s game was leaving him, pushing him into becoming a different bowler.

The tactical set-up of England required him to take more responsibility for his own game, but his physical conditioning and technical troubles were changing the bowler he was. He needed to change, and so more subtle elements of fast bowling began to enter his repertoire. A subtle revolution was taking place.

In the absence of his outswinger, Broad began to come at things from a different angle – literally.

Up until 2016, Broad’s approach to the crease was perfectly standard. 97 per cent of his deliveries (to right-handers) were delivered from the centre of the crease; in 2016, that 3 per cent rises to 35 per cent. Without that movement away from the batsman, the tools at Broad’s disposal were limited, and this can be interpreted as an attempt to replace that movement. It wasn’t hugely effective. That year Broad’s average when going wide of the crease was just under 30, and 27 from the more orthodox position. It was an innovation that was swiftly abandoned. Since then, just 4 per cent of his deliveries have come from that wide angle.

However, this willingness to experiment with angles resulted in arguably the most significant tactical change of Broad’s career. Around this time, Broad began to consistently go around the wicket to left-handers.

In 2015 and 2016, this key part of Broad’s approach comes into his game. Until then, Broad was largely ineffective against left-handers, his average against them (41) was much worse than his average against right-handers (26). Just 23 of Broad’s 71 wickets against left-handers came from round the wicket. At this point Broad was a line bowler, and the switch from right-handed batsmen to left-handed batsmen seemed to mess with that line.

From this round the wicket angle, the absence of that right-to-left swinger was less of an issue. Broad went from bowling about 23 per cent of his deliveries to left-handed batsmen as outswingers, to bowling 39 per cent in 2016, and 45 per cent in 2017. His average with the outswinger to lefties fell from 66.66, to 23.68 – by acknowledging the limitations of his technique, Broad maximised his skills.

You don’t take 500 wickets without compromise.

He could still swing it, of course, as anyone in Nottingham on that famous August morning could attest. In that match, complete with 8-15 and the Ashes tucked under one arm like the Courier Mail, Broad found 2.24 degrees of swing – in his entire career, he’s only once found more swing. Yet 85 per cent of his deliveries in that remarkable spell swung from left-to-right; Broad was capable of this sort of destruction even without that out-swing weapon.

Phase four – Ultra Attacking (2018-present)

Late-Stuart Broad is in a rush.

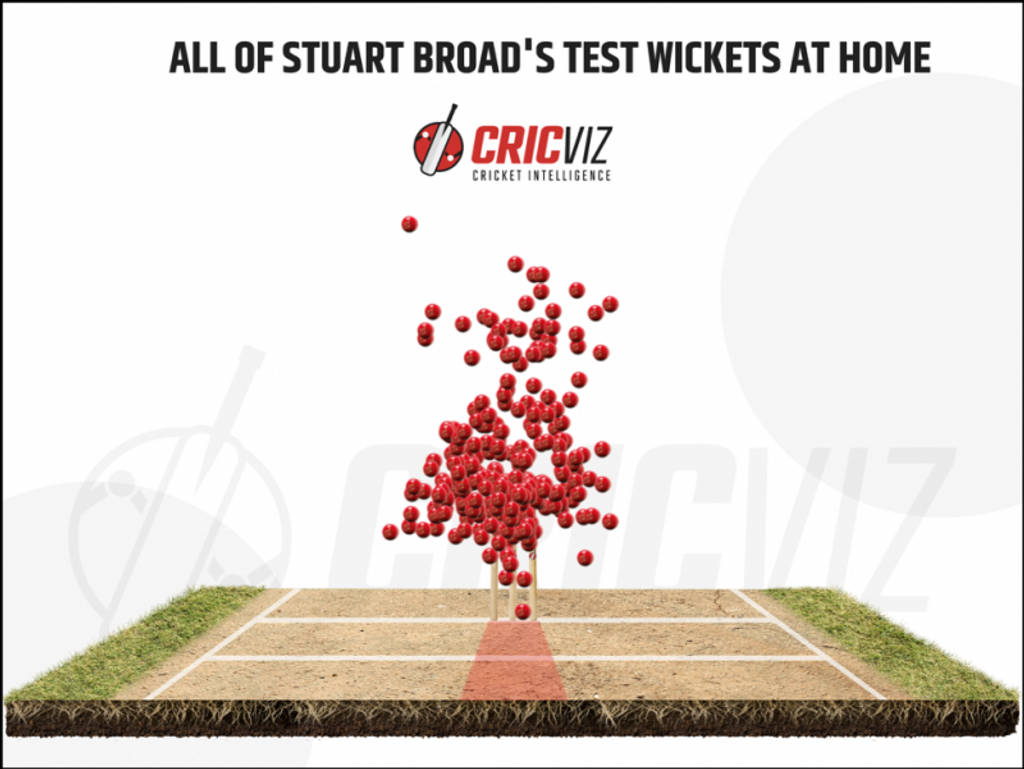

Late-Broad is defined by bowling fuller, more at the stumps, and getting more wickets lbw and bowled. Late-Broad has done away with the fripperies of previous eras, the extravagances of bouncers and hooping swing. Late-Broad wears a headband, because nothing’s getting in his way.

In the last three years, Broad has refined his new ball approach. Whereas before he was always in tension with the tactical plan – and the hard facts of the data – the last few years have seen Broad abandon any restraint with the new ball, and just pitch it up. One of the most common talking points of Broad’s career has been the question of whether he, alongside Anderson, bowls too short with the new ball. While the debate has often been oversimplified – as explained by Nathan Leamon here – it is true that Broad has bowled much fuller of late. Between 2014 and 2017, Broad pitched it up 25 per cent of the time in his new ball spells. Since then, it’s 35 per cent.

The consequence is that he’s targeting the stumps more. From before, targeting the stumps with around 8 per cent of deliveries, Broad now looks to hit 14 per cent of the time. In the 2016 and 2017 summers, Broad bowled 175 deliveries for every lbw or bowled; since then, it’s every 108.

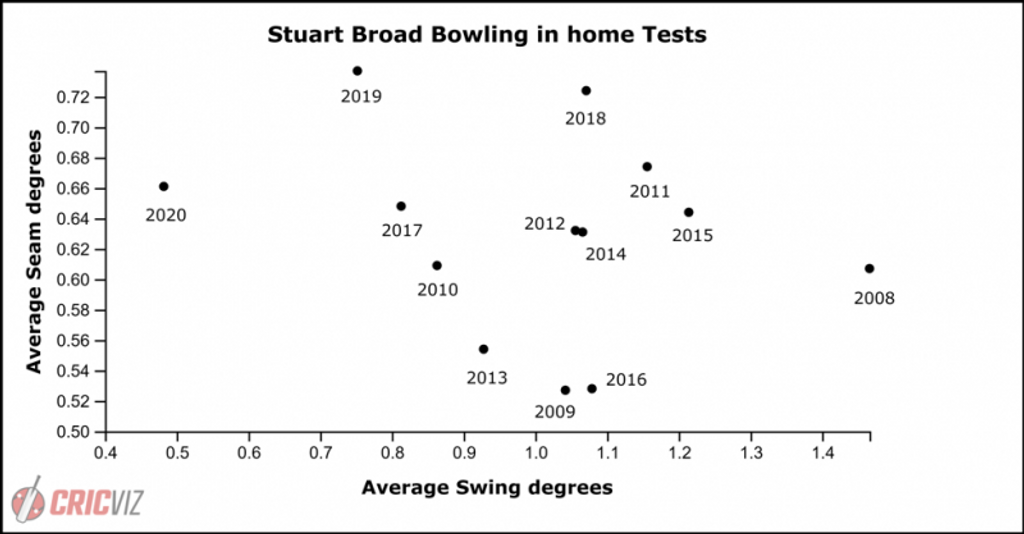

And yet, bowling fuller hasn’t lead to more swing movement. This current incarnation of Broad does not swing the ball anywhere near as consistently as he did in his first decade of Test cricket. The 0.7° of swing he recorded during the 2019 Ashes was the least he’d ever found in a home summer, until this summer where it drops again to 0.5°. Late-Broad is not a swing bowler, but a seam bowler; each of his last three summers have seen more seam than almost any other year of his career.

Seam movement is the less showy, more effective sibling of swing, in England. Later and harder to deal with, it might not draw the eye in the same way, but it takes a lot more wickets. When Broad swings the ball significantly, he averages 28; when he seams it significantly, he averages 17. Hitting that slightly fuller zone with the new ball more often than he had before, and forcing the batsmen to play a lot more frequently – all of these tweaks to his approach mean that even though he doesn’t really swing the ball, he is still a very dangerous customer.

With Broad in a rush to the finish line of his career, and perhaps one eye on 600 wickets, efficiency matters.

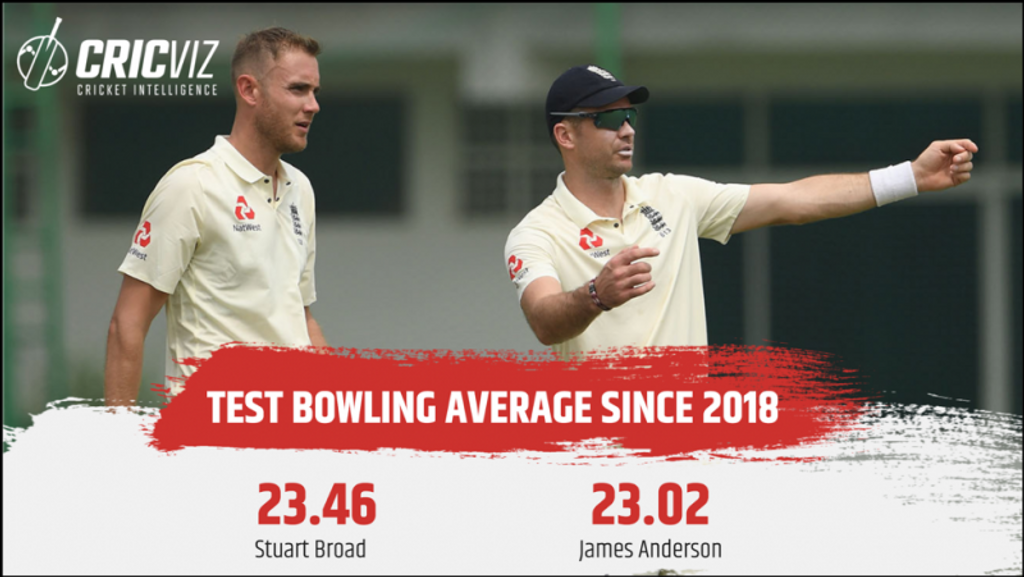

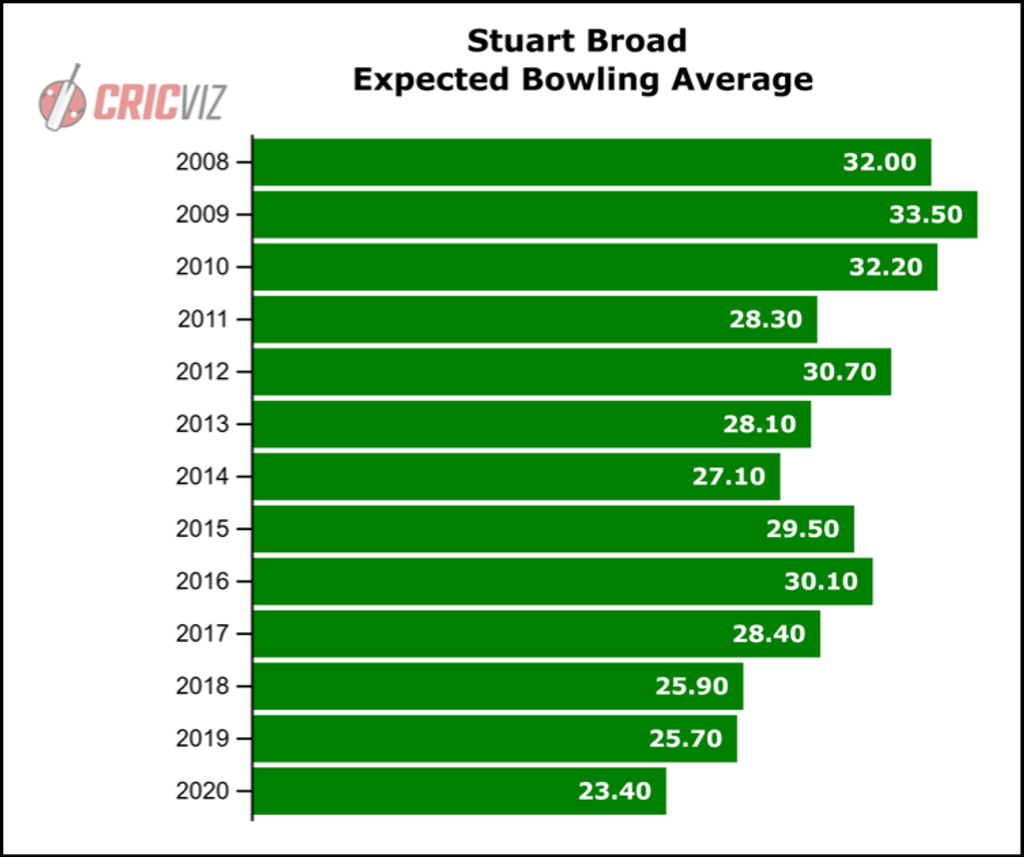

Now, Broad is a more effective wicket-taker than any previous form. It’s telling that the meme-worthy aspect of this version of Broad was the destruction of David Warner, an altogether more consistent achievement. Rather than an afternoon of destruction, Broad offers a constant threat far greater than in previous years. His Expected Bowling Average, essentially a measure of how dangerous the actual deliveries he’s bowled have been, just keeps getting better, and better, and better.

As Broad is always at pains to explain, he and Anderson aren’t the same age. They were born four years apart, and debuted nearly five years apart. In the last few years Anderson has begun to move into the definitive endgame of his career, and even with the disparity in their ages, it would be a surprise had Broad not paid attention to the way his senior colleague has gone about it.

Late-period Anderson is all about minimising waste, less about setting batsmen up with excessive bouncers or hooping changes of swing direction, than bowling the most consistently dangerous deliveries over, and over, and over again.

Perhaps that India tour in 2016 drove it home, or perhaps the Ashes the following year, but while these two older statesmen of the English game are fitter and better than almost any to precede them, time inevitably takes its toll. Preserving energy, and turning as much of the remaining drive and energy into wickets.

Anderson worked that out. Late-Broad has put his own charismatic twist on this, but he’s following the same template.

***

The defining feature of Stuart Broad’s career – so far – has been the ability to change, to transition from being one kind of bowler to another. At the start of his career, Broad could have been any sort of bowler he wanted, but to an extent, he’s never had to commit either way. At different points in his career, he’s played almost every different role: shock bowler, enforcer, economical metronome, new ball striker. He has fulfilled every bit of potential a player could hope for, and then some.