A piece of sandpaper and an eagle-eyed cameraman sent the game into moral meltdown. Lawrence Booth, editor of the Wisden Almanack, puts cricket’s latest cock-up in perspective.

Did the punishment fit the crime? It really depends how you defined the crime. Because if a year out of the game seemed a bit much for scraping sandpaper on a ball – so feebly, it turned out, that the umpires didn’t even impose a five-run penalty – then Australia had already set themselves up for a fall that sat somewhere between Greek tragedy and Shakespearean farce.

The cock-up in Cape Town was one of those perfect storms that cricket throws up every few years. It involved a team that had been allowed by its own board, coaches and media to behave like brats; the world’s most unpopular player; plenty of sanctimony and moralising (in this, cricket remains in a league of its own); and all the failings which make us human. It even had a spot of Ealing comedy, as someone tried to shove the evidence down the front of his trousers.

Cameron Bancroft and Steven Smith lying to the umpires on day three in Cape Town

Cameron Bancroft and Steven Smith lying to the umpires on day three in Cape Town

Throw in the sanctity of the Baggy Green – a cult so persuasive that many Australians have internalised the cliché that their cricket captain doffs the cap only to the prime minister – and we had it all. The media went to town, a nation into mourning.

As others have pointed out, ball-tampering is an art almost as ancient as match-fixing. That doesn’t make it right. Equally, let’s go easy on the outrage. No, the problem lay in the chutzpah – and in what the chutzpah said about where this Australian team had gone wrong.

A bad-tempered series had provided two gems even before the world came crashing down for Steve Smith, David Warner, Cameron Bancroft and – by his own volition – Darren Lehmann. First we had Warner lecturing the world on the famous “line” – a demarcation of vague whereabouts that assumes sharp focus when Australia feel others have crossed it.

Darren Lehmann has since resigned from his position as coach of Australia

Darren Lehmann has since resigned from his position as coach of Australia

Then there was Lehmann complaining about the behaviour of the Newlands crowd. He had a point, of course: their taunting of Warner’s wife, Candice, showed how far the world still has to go to move past sexism. But wasn’t this the same Lehmann who had encouraged Australian fans in 2013 to send Stuart Broad home in tears?

Hypocrisy is supposed to be an English vice, yet here was another thing the Australians now seemed to be doing better. The trouble was, they just didn’t see it. Convinced their way was best, they felt invulnerable. It’s hard otherwise to explain why Bancroft felt he could rub sandpaper on the ball and not be spotted by any of the dozens of cameras dotted around Newlands.

But this was about more than arrogance. To an unparalleled degree, Australia’s administrators have invested in the squeaky-clean reputation of their cricketers as they seek to keep young families glued to the Big Bash. And events at Cape Town came at a sensitive moment for negotiations over the latest five-year TV rights. As one corporation after another distanced themselves from the shenanigans, it was easy to imagine broadcasters and spectators going the same way. The loss of Magellan as team sponsors, only eight months into a three-year deal, was especially significant.

And so the players hadn’t been punished for ball-tampering, said James Sutherland, the chief executive of Cricket Australia. They had been punished for dragging the name of Australian sport through the mud. They had messed with the brand. Modern cricket knows no greater crime.

Yet while Smith, Bancroft and Lehmann – perhaps even Warner – deserved our sympathy as they struggled to make it through press conferences five days after the scandal broke, not everything stacked up.

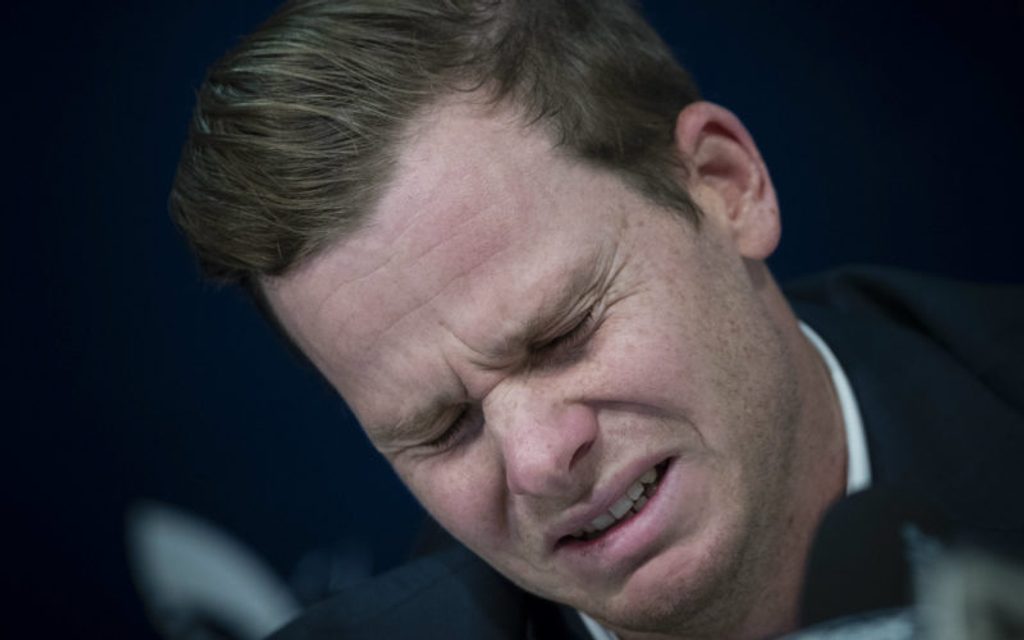

Steve Smith held an emotional press conference after his ban was announced

Steve Smith held an emotional press conference after his ban was announced

The initial findings of CA’s integrity unit, for example, settled on a best-case scenario: only three players were involved, Lehmann and the coaching staff were in the dark, and Australia had not previously tampered with the ball. With the best will in the world, this was hard to credit. As one Australian journalist put it to Lehmann during his resignation press conference: why should anyone believe in the team’s previous innocence when the players had been implicated by the board for lying?

It seemed harsh to dismiss Smith’s remorse as crocodile tears, especially with his dad standing behind him as he performed his mea culpa at Sydney airport. Who wouldn’t have broken down in the circumstances? And there was some truth in the suggestion by the Australian Cricketers’ Association that year-long bans seemed “disproportionate”.

They had messed with the brand. Modern cricket knows no greater crime

But it’s also reasonable to ask what exactly Smith expected when he failed to nip Warner’s sandpaper brainwave in the bud, then tried to get away with it, both on the field during his discussion with the umpires, and in the ensuing press conference. His own description of the affair as “a failure of my leadership” was spot on.

Lehmann was right to resign too. Under his guidance – sometimes explicitly so – Australia’s behaviour went backwards, and most observers gave them a free pass. If he knew about the sandpaper fiasco, he wasn’t telling the truth; if he didn’t, he had lost control of the dressing-room. Either way, he had to go, a powerful “I told you so” from Mickey Arthur, his predecessor, ringing in his ear.

David Warner has had less sympathy from the cricketing public for his involvement

David Warner has had less sympathy from the cricketing public for his involvement

For Warner, there was less sympathy – and a horrible moment when he and his wife emerged to face a media scrum at Sydney airport carrying their two young children. It was the most vulnerable vignette of his career.

He, too, benefited from gullible coverage. Too many swallowed the story that he had morphed from The Bull to The Reverend. They overlooked his obnoxious talk about “hatred” and “war” before the last Ashes, and the role he played in the vilification of Jonny Bairstow at Brisbane. The attitude of much of the Australian press appeared to be: he may be a moron, but he’s our moron. World cricket will be better off without him.

And, in a year’s time, it will benefit from the return of Smith, who will have the lure of a World Cup and an Ashes series to keep him going in the dark months ahead. Here’s hoping he sees the light.