CricViz analyst Ben Jones takes a close look at Olly Stone, an underappreciated member of England’s high-pace triumvirate.

For England’s Test side, the 2017/18 Ashes was not the disaster of 2013/14. Joe Root’s team spluttered through the winter, competing with diminishing effectiveness as the series wore on. But it was a calmer, more dignified defeat than the previous tour. The wheels squeaked, didn’t always roll smoothly, but never came off.

Perhaps as a consequence, the defeat was analysed through a more subtle lens than tours gone before. Many recognised that Australia having arguably the best batsman of the modern era, as well as an elite attack operating at the peak of their game, made things exceptionally difficult. All that while England had banned their own star all-rounder and made some highly questionable selection calls throughout. There was an admission among even the most partisan of the English press that Australia were simply a better prepared and higher quality side.

Amongst all the opinions was one straightforward fact – the gulf in speed between the two bowling units was vast. Across the five Tests, Australia bowled 715 deliveries up above 140kph/87mph; in comparison, England bowled just 46. While you don’t need ball speed to succeed in Australian conditions, it certainly helps. And England didn’t have it.

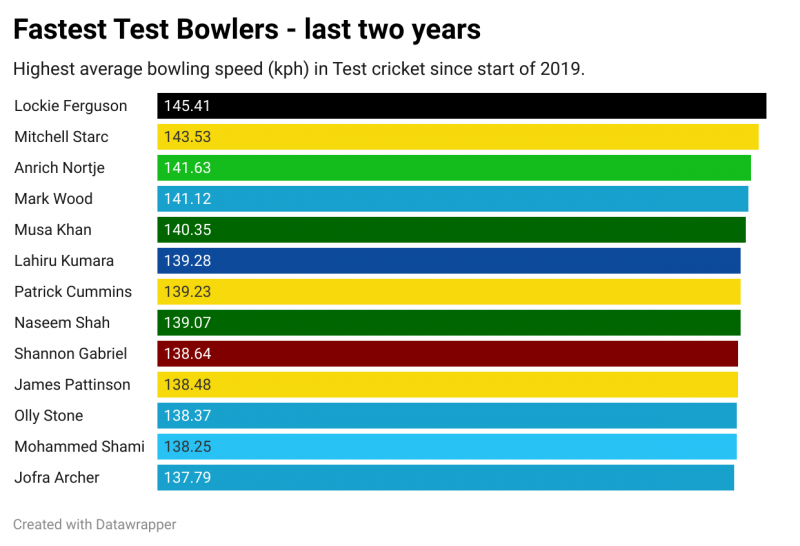

With that criticism still ringing in his ears, Root is unlikely to make the same mistake twice. In preparation for the Ashes this winter, England have paid particular attention to bowlers who can consistently bowl at 90mph and have spent time and caps nurturing them when the opportunity has arisen. The result of that focus is that, six months out from the first Test at the Gabba, England have three of the 13 quickest bowlers in the world in their ranks: Jofra Archer, Mark Wood and Olly Stone.

Now those three bowlers have taken rather different routes to the top level, but it’s fair to say that the bulk of media and fan attention has fallen on the first two. It’s understandable. Archer’s story is unique and compelling, while his performances in white-ball cricket had earned him world-class status before he’d even bowled a ball in Test cricket. Wood matches his elite pace with an injury-prone streak that inherently creates jeopardy and interest, as well as a bubbly and confident personality that endears him to seemingly everyone he encounters. The pace may be the exciting element of these two bowlers, but both have stories which compel beyond the speed gun.

Yet while Wood and Archer are the stars of the show posing for the paparazzi, Stone is more easily imagined trying to grab a reporter’s attention to say that it’s actually spelled Olly, not Ollie. Breaking through at Northamptonshire as a teenager before moving to Warwickshire in his mid-twenties, Stone has followed a fairly traditional route into the England XI, playing a handful of games for his country, coming in and out of the side, perhaps suffering as a consequence. It’s not a tale which invites features, interviews, deep-dives: familiarity does not breed content.

But the quality he possesses shouldn’t go under the radar: Stone’s bowling average in Test cricket (13.85) may have only come from two matches, but it still represents an outstanding start to a career at this level. His debut success against Ireland may have been downgraded due to the quality of opposition but in India he took 4-68 in extremely spin-friendly conditions, against a batting line-up of the very highest quality.

What’s more, Stone’s Expected Average (24.5) is the best of any England seamer under Root’s captaincy; his exceptional ‘actual’ average may be the result of a small sample size, but the xA suggests that the performances themselves have been brilliant. In his brief Test stint, Stone hit a good length more often than either Archer or Wood, a statistic muddled by spells of almost entirely bouncers for the established pair, but one which does point to Stone’s broader skillset. He swings the ball more than either Wood or Archer, and he seams the ball more than Wood. His ‘English-condition’ skills are arguably the best of the three.

Those performances haven’t only come in an England shirt either. While his arrival in the Test side may have been fast-tracked because of his speed, Stone has more than earned his place based solely on domestic performances. Since the start of 2018, Stone is only 38th on the CC/BWT wicket-taking list among English seamers, but of those to take 50+ wickets in that time, only two men (Darren Stevens and fellow England squad member Ollie Robinson) have a better average. There are concerns about his control, as shown by an economy of 3.4rpo in recent seasons, but it’s countered by the best strike rate of anyone on that list. Bowl this quickly and you’ll always be fragile, conceding ground in terms of volume and longevity, but when it comes to pure effectiveness, you steal a march. Stone deserves substantially more praise and focus than he has received.

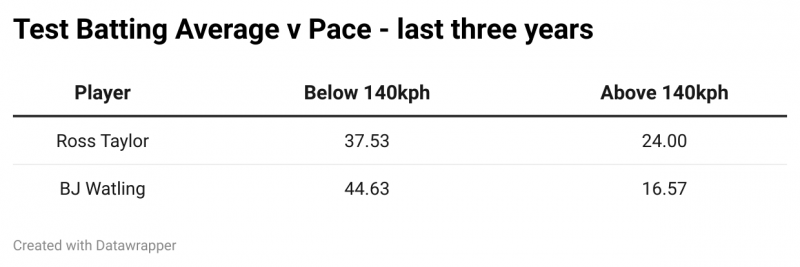

This series may offer a chance to change that. Ross Taylor and BJ Watling are established top-class Test batsmen, but both have shown weaknesses against high pace in the last few years – for all the swing and seam on offer with the Dukes ball, England may well be best served to have one of their (likely) four seamers as a proper pace option. The absence of Archer means that it’s a straight shootout between Stone and Wood for that spot. Regardless of which way they go, anticipated rest and rotation should give the Warwickshire quick the chance to play at least one Test against Kane Williamson’s side. Indeed, the chance may even come in front of a home crowd at Edgbaston, with attendances recently boosted by the news of 18,000 fans being allowed in.

Those fans, and the importance of the upcoming summer, are not irrelevant here. A couple of weeks ago head coach Chris Silverwood rather clumsily painted the Test season ahead as simply a means of preparing for the Ashes series which will follow it. Speaking to the press, Silverwood discussed how playing against New Zealand and India would be key in his side’s development for the Australian challenge, rather underselling what an achievement beating those sides would be in isolation. The top two-ranked sides in the world are in town, crowds are back, and England seemingly have their minds on how best to Uber from Brisbane Airport to their Airbnb.

While nobody disputes the primacy of the Ashes for the majority of England fans, it does point to England failing to strike a balance between preparing for away tours, while maintaining focus on the matter at hand. At home, the art of selection is in part balancing the need to win now with the need to win later. The decision to pick Wood (who averages 45 in England) over Stuart Broad for the first Test against the West Indies last year is a great example of what happens when you get this wrong, when you turn too much to the future.

While in that instance, the blame fell firmly on Ed Smith – despite Smith having no official say in the playing XI, and the looming sense that had captain Ben Stokes wanted Broad to play ahead of Wood, then Broad would have played – there will be no equivocation this summer. Previously, the playing XI was Silverwood and Root’s call, but with the helpful screen of Smith when needed; now, the screen is gone. Tilt things too far in favour of winning now rather than winning in Australia, and you risk damaging your own chances of creating a successful legacy. But tilt things too far the other way, and you risk not making it to the Gabba at all.

And so, Stone may prove a helpful third way, a nod to Brisbane but with eyes firmly on Birmingham, and the home summer ahead. He may have been somewhat underappreciated up to this point, but it may be the unturned Stone where England find the key to their Ashes ambitions.