Jos Buttler is in the form of his life – but how good can he get? CricViz analyst Ben Jones examines Buttler’s data to see if the England star can reach the level of his South African idol, AB de Villiers.

Ben Jones is an analyst at CricViz, the cricket intelligence specialists

In May, after 114 Tests, 228 ODIs and 78 IT20s, AB de Villiers, the greatest batsman of his generation, announced his retirement from international cricket. Three days later, Jos Buttler walked out to bat at Lord’s against Pakistan, returning to Test cricket after an 18-month hiatus during which he played just four red-ball matches. The timing was neat.

More than any other, de Villiers refined the innovation and aggression in batting which became the hallmark of the subsequent generation, none of whom resemble the South African quite as closely as Buttler.

Indeed, Buttler has spoken publicly of de Villiers as an inspiration for his batting, and has made his ambitions clear: “That’s the role I want to play in English cricket”.

Killers at the death

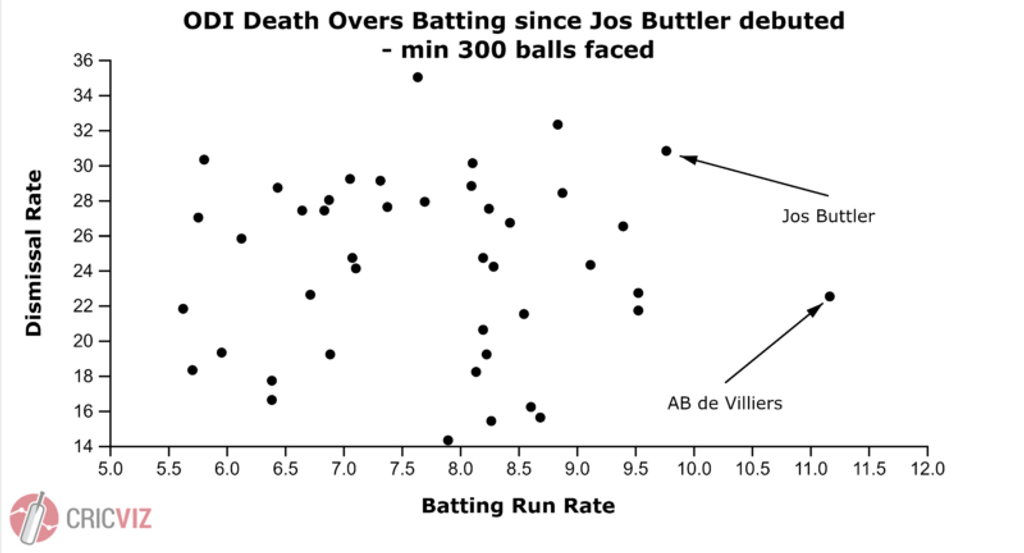

It’s the death (last 10 overs in ODIs) where Buttler and de Villiers stand out most of all. Since the Englishman’s ODI debut, de Villiers is the only man to score faster than Buttler at the death.

The gulf between de Villiers and the chasing pack is remarkable, but Buttler is still leading that group. He is the closest thing de Villiers has had to a competitor in recent times, and his superior dismissal rate suggests that whilst the South African may be more destructive, Buttler is harder to stop.

So, for English fans approaching a World Cup in need of a talisman – how close to de Villiers can Buttler get? Using CricViz data as a guide, here are the key areas in which Buttler can take his game to the next level.

HOW CAN BUTTLER REACH AB?

1. Lose the gloves

The strain of keeping, even in a 50-over match, is detrimental to batting performance. When keeping in ODIs, de Villiers’ batting average was a strong 48.89; when not keeping, it leapt to a stratospheric 69.00. Buttler’s numbers to date suggest this relationship could be the same for the Englishman. In List A cricket, Buttler averages 43.08 when he keeps wicket, and 57.42 when he doesn’t, also scoring marginally faster without the gloves than with them.

AB benefited from ditching the gloves

AB benefited from ditching the gloves

Jonny Bairstow needs to take the gloves. The Yorkshireman is in electrifying form with the bat, and many may be wary of disrupting him. But Bairstow is a streaky player, as shown by his diminished Test returns of recent, and his ceiling as an ODI batsman is lower than Buttler’s. By having Bairstow take the gloves in this format of the game, England could be maximising Buttler’s effectiveness for years to come.

2. Move up the order

Despite the aesthetic and technical similarities between de Villiers and Buttler, they have rarely performed the same role. 131 of de Villiers’ ODI innings have come at No.4, more than in any other position, whilst most of Buttler’s innings have come at No.6. England may have revolutionised their ODI batting, but Buttler has been consistently used as a finisher – albeit a floating finisher – in recent times.

Yet on those occasions when Buttler has batted at No.4, he’s averaged 56.33. AB averages 53.11 batting there.

When Buttler has batted at No.4, he’s averaged 56.33. AB averages 53.11 batting there

Of course, Buttler has only batted there on eight occasions, generally when England are plundering the opposition on a road, and that’s reflected in his scoring rate of 9.94rpo. However, it suggests that Buttler can bat at full throttle without necessarily compromising his contribution in terms of runs. A useful trait.

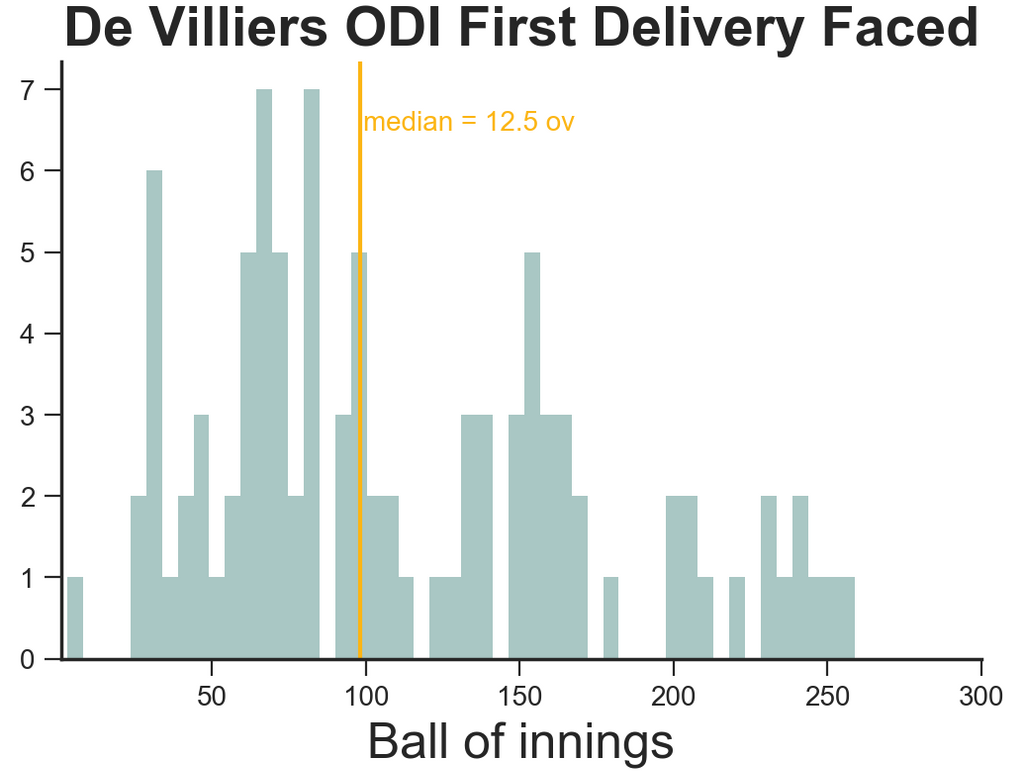

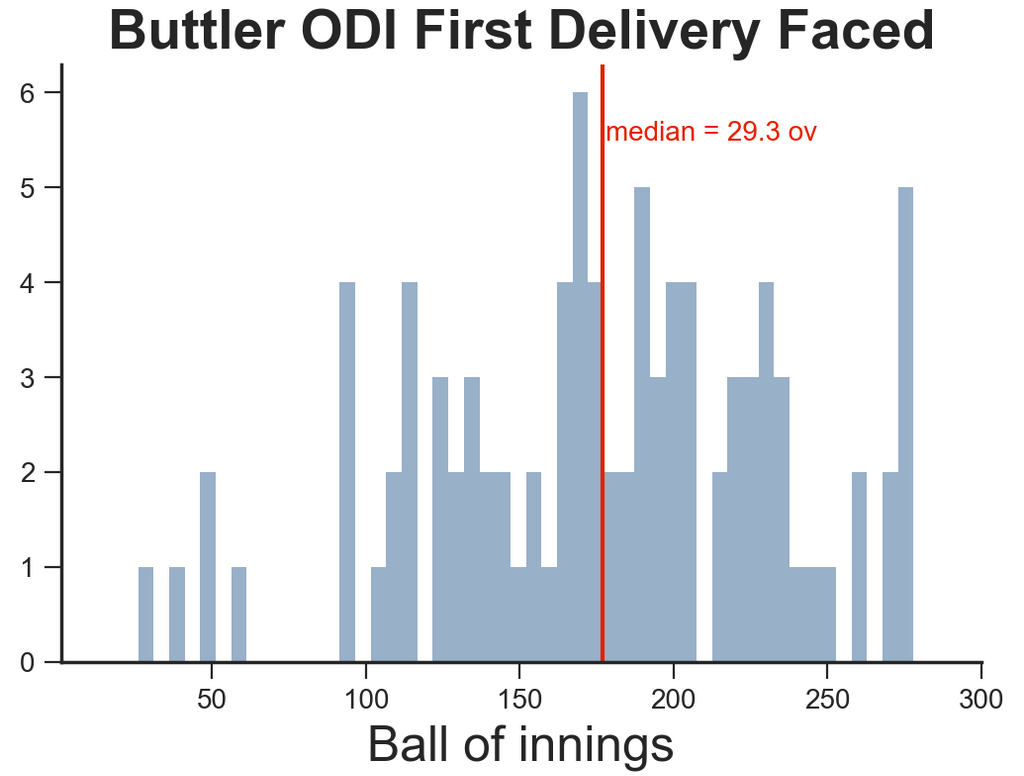

Therefore, England can afford to bat Buttler higher. Getting him in the top four would see him exert more influence on the innings, given that currently on average, he enters the crease with 29.3 overs already having been bowled. Since Buttler debuted, de Villiers, for all his destructive powers, arrived at the crease on average after just 12.5 overs, giving him almost 20 extra more to play with.

Moving Buttler up could also have the effect of bringing the best out of Eoin Morgan. Since the start of 2017, only Rohit Sharma scores more quickly than Morgan at the death in ODIs (min 50 balls). England’s captain is an elite finisher, and should embrace this role, particularly given that moving Buttler up the order supports his all-out-attack philosophy.

3. Adjust his pacing

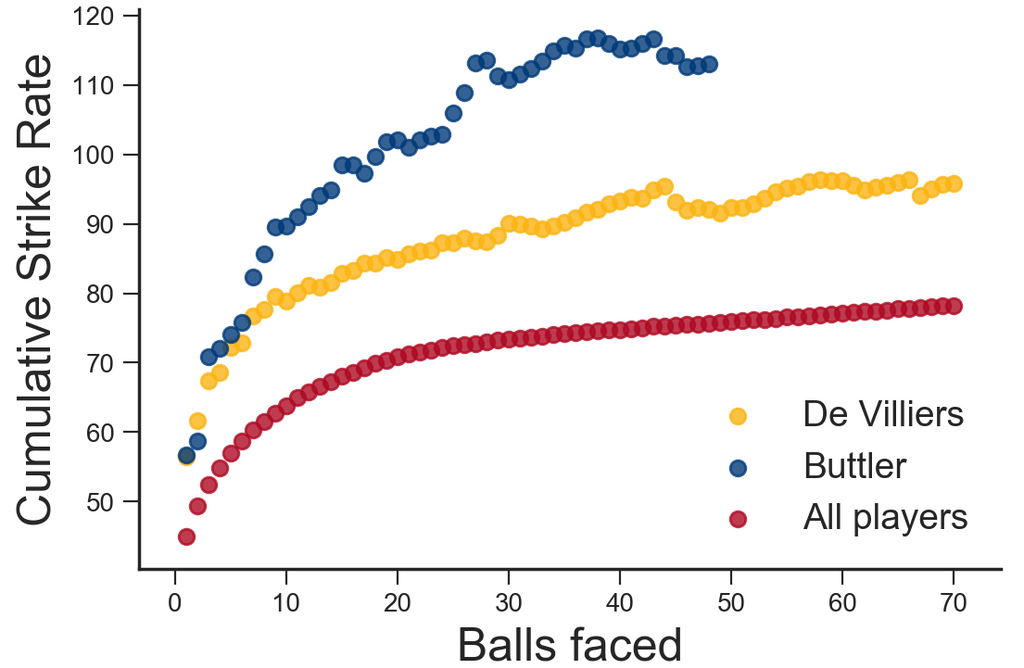

One of Buttler’s most thrilling qualities is his acceleration, as illustrated by the minimal time he takes in an innings to get his strike rate up above 100. Across his career, Buttler takes an average of just 19 deliveries before he’s scoring at over a-run-a-ball; by comparison, since Buttler debuted, de Villiers took 92 deliveries. Considering that de Villiers himself is above the average acceleration, this shows quite how rapidly Buttler begins an innings.

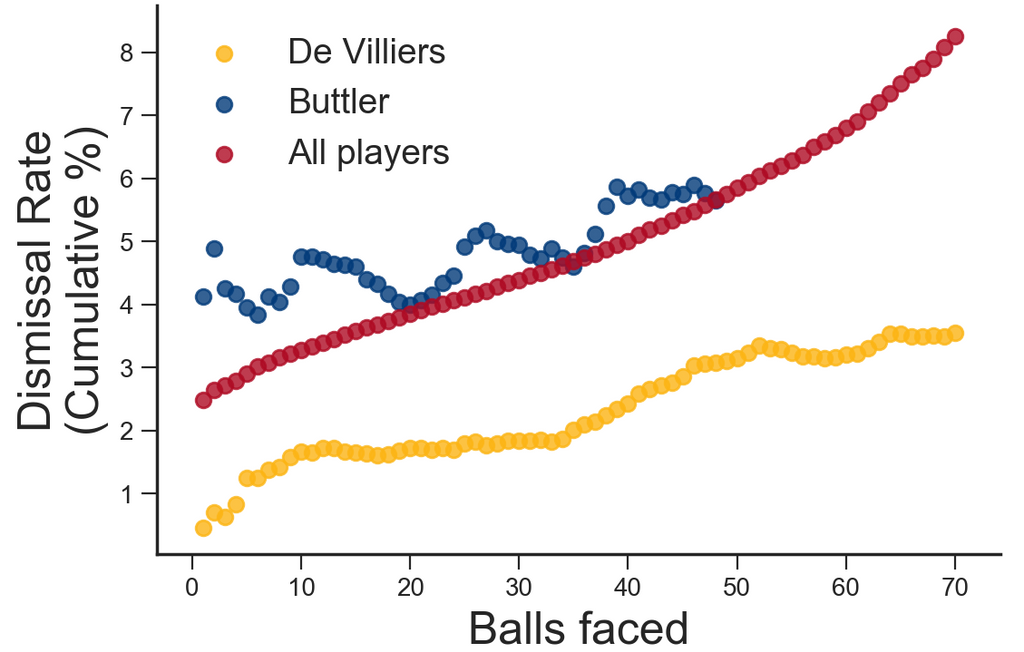

The downside is that Buttler is dismissed early far more than the average player. As this chart shows, for the first 20 balls of his innings he’s far more likely to be dismissed than most.

Both these patterns can be explained by Buttler’s role – finishers obviously start quickly with less regard for their wicket – but if he’s going to successfully move up the order he’ll need to adapt this pacing. His recent match-winning century against Australia at Old TraffordAt No.4, his century at Old Trafford should be the template. After 30 balls on that day, he was on 27, well below his usual strike rate of 111 at that point in an innings – but he hadn’t played and missed at a single delivery. Subsequently, the Australia bowlers didn’t find the edge of Buttler’s bat for his last 66 deliveries, further showing that once set, Buttler can be just as controlled as most ODI players.

4. Sweep more effectively, with greater flexibility

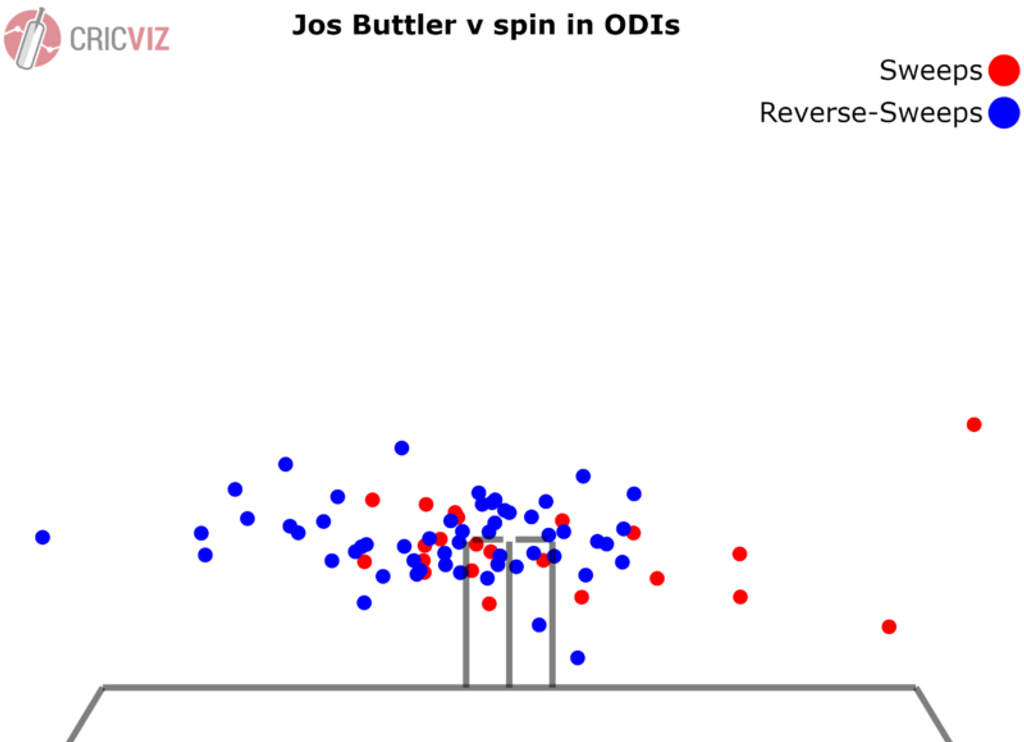

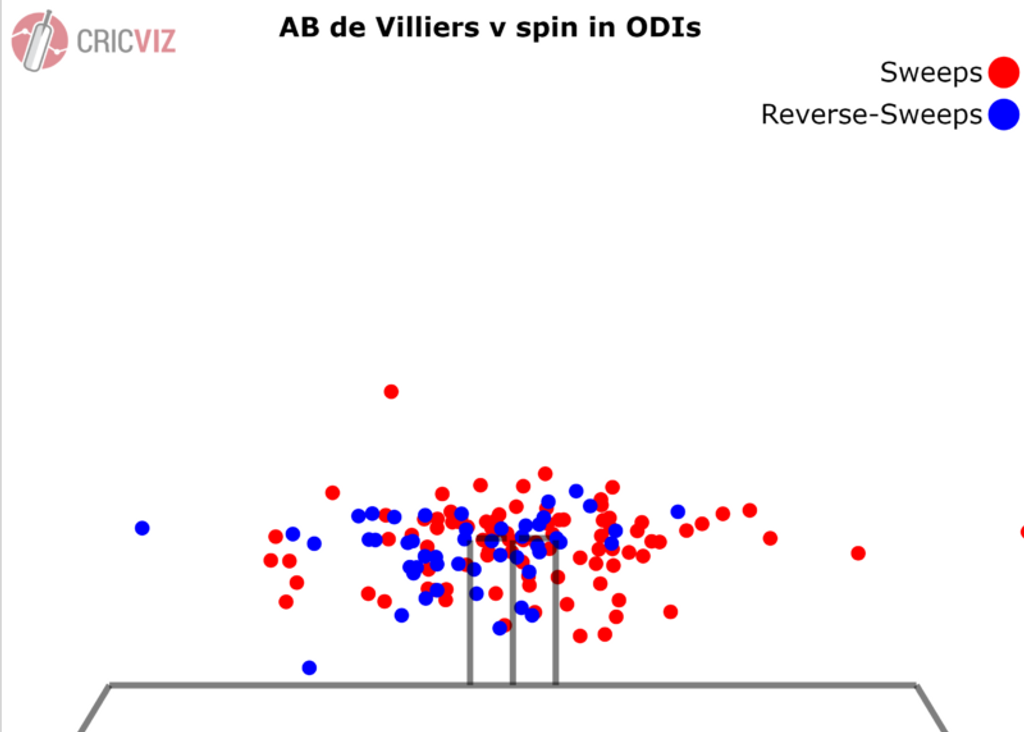

The sweep and the reverse-sweep are staples in the modern batsman’s repertoire. Versatility with these strokes is a fundamental part of being a 360° player, and yet remarkably, it’s an area where Buttler slightly struggles. As shown below, Buttler only really plays the conventional sweep shot when the ball is straight, and plays the reverse-sweep mainly to balls outside off-stump, his choice of conventional sweep or reverse-sweep dictated by the line of the ball. By contrast, de Villiers was happy to shimmy around the crease a lot more, hitting similar balls in opposing directions.

Bizarrely, given the original inventiveness of the reverse-sweep, this makes Buttler a touch predictable. Captains can instruct their more accurate bowlers to bowl on one side of the wicket, knowing that Buttler is unlikely to move across and sweep from outside off into the leg-side. Increased flexibility brings increased reward; de Villiers scored at 9.36rpo with his sweeps against spin, whilst Buttler only manages 7.82rpo.

Of course, Buttler has a good record when facing spin, averaging 53.26 and scoring at 6.31rpo, faster than de Villiers. Spin is not a weak area for him. However, whilst the South African might not score as quickly, he is harder to tie down, as shown by a notably lower dot-ball percentage. In order to bat up the order, Buttler will need to resist being stymied by the slower bowlers; being able to sweep the same delivery to either the leg-side, or the off-side, would be an excellent addition to his considerable bag of tricks.