CricViz analyst Ben Jones examines the contrasting home and away Test records of Rohit Sharma.

January, 2021. Late into the evening in Sydney, Rohit Sharma was looking good. In fact, if we’re totally honest, he was purring. Having just brought up his half-century, India were 92-1 in nominal pursuit of 407, but with their sights set on a draw that would keep the series alive. The pitch was flat, the chance was there, and Rohit’s clinical elegance was in full flow. The stage was set, the lights dimmed, the opportunity there to be grasped.

And then, he was gone. A short-ish ball from Pat Cummins was pulled deep towards the rope, where Mitchell Starc took the catch. It was a shot which angered many, the question of his temperament once again raised, his long-form ability scrutinised.

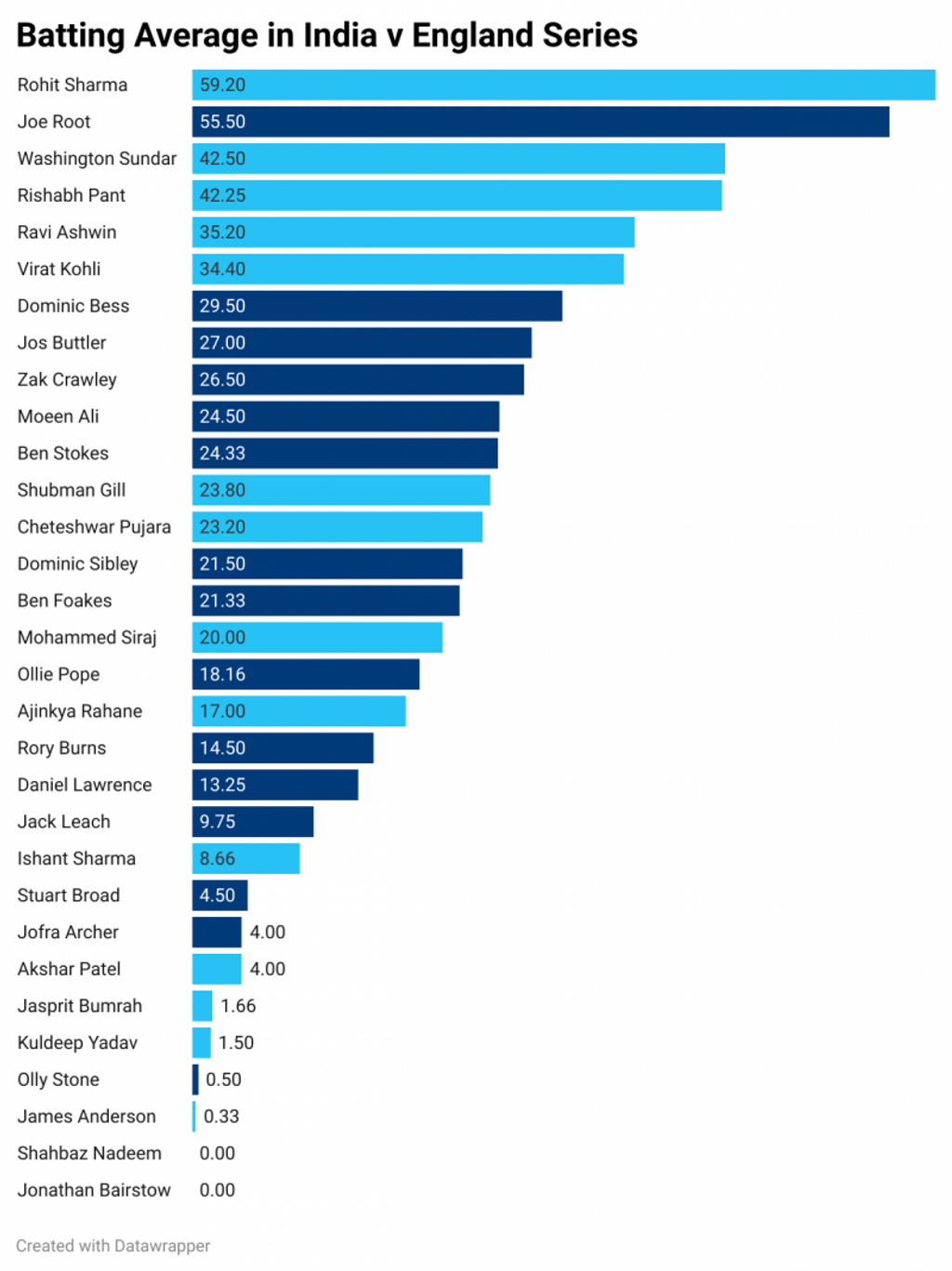

It was fair enough, in some respects. His average in Australia this winter, 32.25, was nothing to write home about, while equally being no huge concern. And yet here we are, three Tests into another big series with Rohit topping the averages, having registered India’s only top order century, and generally having put on an absolute clinic in how to bat in difficult conditions.

CricViz: Rohit Sharma has the best average of any batsman so far this series

CricViz: Rohit Sharma has the best average of any batsman so far this series

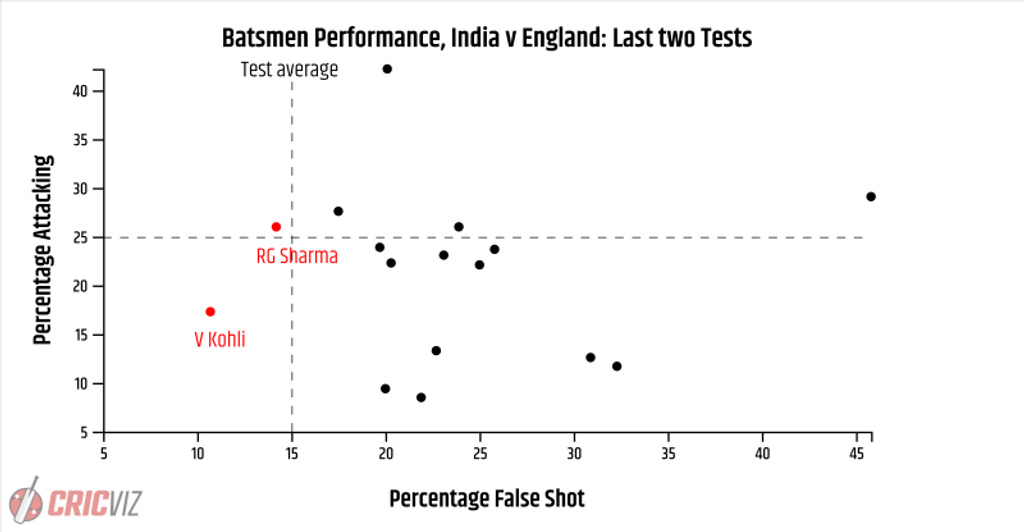

Scores of 161, 26, 66 and 25* are solid at any time in a player’s career, but given the borderline existential crisis those watching this series have indulged in over the last two pitches, it’s a minor miracle. While everyone else has been slipping and sliding on the ice, Rohit has skated around serenely, a gentle backdrop of classical music accompanying his calm control. His false shot percentage, just 14 per cent, is bettered only by Virat Kohli, who found that control by removing attacking intent; that’s not Rohit’s style.

CricViz: Only Virat Kohli has a lower false shot percentage than Rohit Sharma this series

CricViz: Only Virat Kohli has a lower false shot percentage than Rohit Sharma this series

Rohit does not lack for adoration, in a broader sense. Captain Mumbai Indians that many times, win that many trophies, score that many ODI tons as an opener and stake a claim to being the greatest the game’s seen in that position – you don’t go underappreciated. Yet these last two Tests haven’t seen him rained with the compliments you’d imagine, and there are two main reasons for this.

One is that, to some extent, he’s had the best of the conditions to play in. That first day in Chennai wasn’t noticeably easier for batting than the second, but the first few hours of play were a touch more typical. It was during that period that Rohit did make hay, scoring 80 runs before lunch on Day 1, a tally that only two Indians (Virender Sehwag and Shikhar Dhawan) have outstripped since 2006. He cleared out the safe before England even realised there was even a heist on the cards.

The other reason, perhaps, for why his excellence has been underplayed, is that we have almost come to expect this level of brilliance from Rohit in India. Much has been made of the Rohit moving to being an opener, as if that is the big change that has sparked his princely form. It isn’t. The love affair for Rohit is not the place in the order, but the place itself. Rohit Sharma is in love with India.

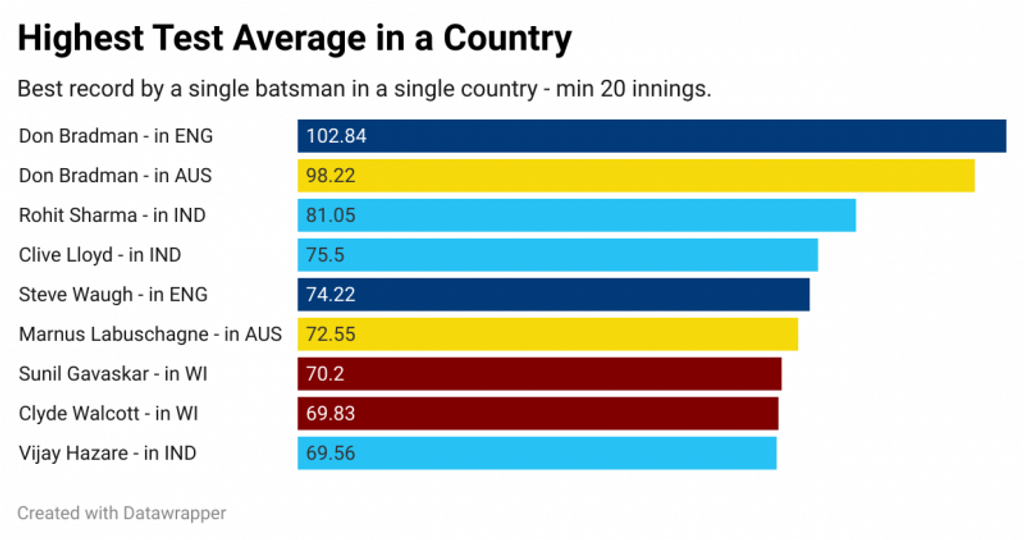

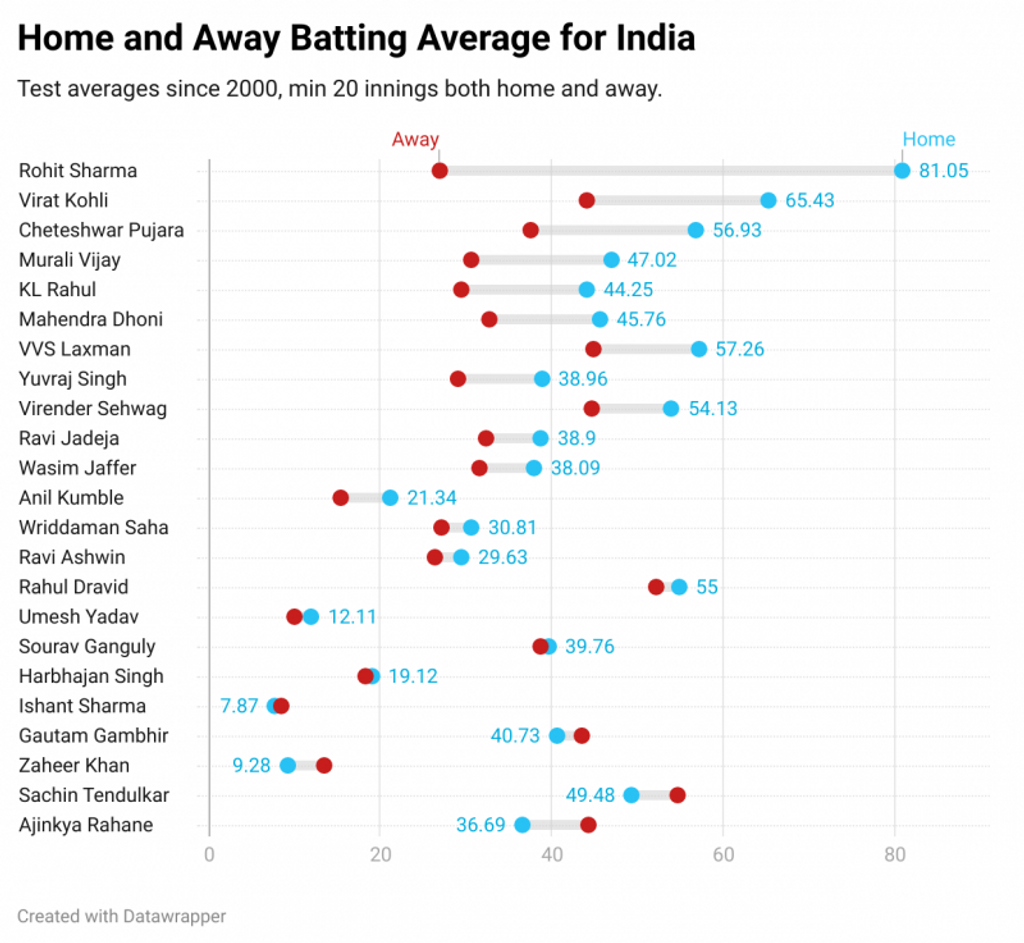

His average at home, a vast 81.05, is not just the highest average for an Indian at home. It’s not just the highest average for anyone in India. It’s the third highest average for a single player, in a single country, in Test history.

CricViz: Only Don Bradman averages more in a single country than Rohit Sharma does at home

CricViz: Only Don Bradman averages more in a single country than Rohit Sharma does at home

His record as an opener isn’t actually better than it was further down. In home Tests batting in the middle order, he averages 85.44, higher than the 77.45 he averages opening the batting.

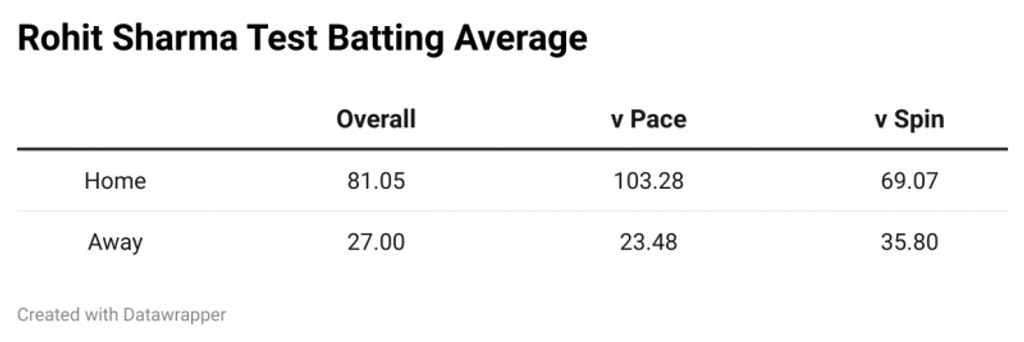

CricViz: Rohit Sharma averages substantially more at home than away, especially against pace

CricViz: Rohit Sharma averages substantially more at home than away, especially against pace

The natural counter to that is that his away record does loom. The difference between his average at home and his average away, 54.05, is the highest of any player in the history of the game to play 20 innings both on the road, and in their own country. While this is largely a consequence of Rohit’s hometown brilliance than something which points to an exceptionally poor record away from home, there are still plenty of questions to be asked.

Given that the table above shows pace to be the real issue overseas, you can ask whether there’s a weakness in his strength. His iconic stroke in white-ball cricket is that brutal pull shot, and it’s translated into Tests. He’s played 125 pull shots in this form of the game and been dismissed only four times, averaging 67.50 with the stroke. However, in India, that average is 157; outside India it’s 37.66.

Perhaps he’s a touch trigger happy with the stroke on surfaces where the ball can get bigger on him, but more broadly, Rohit nails the short ball as well as ever when he’s away from home, averaging 74 against it, and scoring at quicker than 5rpo. This isn’t a case of a player being shocked by pace and bounce.

The issue is against the fuller deliveries, that inbetween length. Against these deliveries, outside of India, he averages 18.42. Against the nip backer, the ball moving in off the seam into his pads, he’s averaged 11.40. Rohit struggles with the moving ball, and the ball moves less in India.

But let’s not get overly distracted by the negatives, because the point is that Rohit’s brilliance in India is historic. He will likely not sustain it, because almost nobody in history has – nobody at all in the modern, more widely competitive era of the game has done so. But for now, his record at home is something beautiful.

We place too much expectation on white-ball legends to nail Test cricket. Maybe it’s the fact that our brains are so attuned to watching them dominate that we sit, Pavlovian drool pouring out of our mouths when they walk to the crease, unconcerned about the format. The challenges are different, and separate, as are the challenges of cricket at home, and cricket away from home. With both we should be careful not to let technical, sporting reasons bleed over into moral criticisms, complaints about character. Racking up match-winning ODI scores is not necessarily easier than making Test hundreds. Home conditions are not always easier than away.

Because there’s a counter-example, right there in this team. Ajinkya Rahane, the captain who conquered Australia, is averaging less than every other Indian top order player this series. And yet, just like with Rohit, the reaction is muted, because this is what Rahane does.

CricViz: In terms of home-away average differential, Ajinkya Rahane is at the opposite end of the scale to Rohit Sharma

CricViz: In terms of home-away average differential, Ajinkya Rahane is at the opposite end of the scale to Rohit Sharma

Of every established Indian this century, nobody has a bigger gap between home and away averages in the other direction than Ajinkya Rahane. The vice-captain averages just under 37 in home Tests, but just under 45 away from home. India have made the choice to accept this pattern, this mediocre record at home, partly because of Rahane’s leadership skills, and partly for the sake of consistency. Yet with Rohit, India don’t have to go the same way.

India’s great depth in playing resources means that more than any other nation in the world, they have the chance to create complete flexibility in their XI. Having overseas specialists, and Indian specialists, is no bad thing when you have the number of quality players that Kohli has at his disposal. If a player emerges who is better suited to combatting the swing and seam movement which can be more pronounced overseas, then it would be fine for India to take Rohit out of the XI, and go a different direction.

Perhaps Rohit will make technical changes, overcome his issues and dominate in England. It would not be outrageous, given the way he has excelled in every single other area of the game. But accepting a player’s flaws, understanding their ability and their weakness, does not have to equal selection in all conditions, in the manner it has with Rahane. It can also mean allowing them to flourish in the situations best suited to them, and nothing more.