CricViz analyst Ben Jones examines the remarkable recent improvement of Alex Hales as a T20 batsman.

Alex Hales isn’t a debate. He isn’t a moral dilemma. He isn’t a problem, a bad example, a talking point or MacGuffin. Alex Hales is one of the best T20 batsmen in the world.

Over the past few years it’s been easy to get lost in the discussion around the (formerly) England batsman, to distract yourself from the player himself and see his career simply through a lens of trust and mistrust, of selection and non-selection. In a world where every half-century is “laying down a marker” or “making a statement”, it’s easy to zoom in too far, and to miss the overall picture.

In the last 12 months or so, Hales has been absolutely superb. Since the start of 2020, he has scored almost 1,600 T20 runs at 9.3rpo, or a strike rate of 156, if you prefer. Nobody has scored more; nobody to even get close to scoring more can match his rate of scoring.

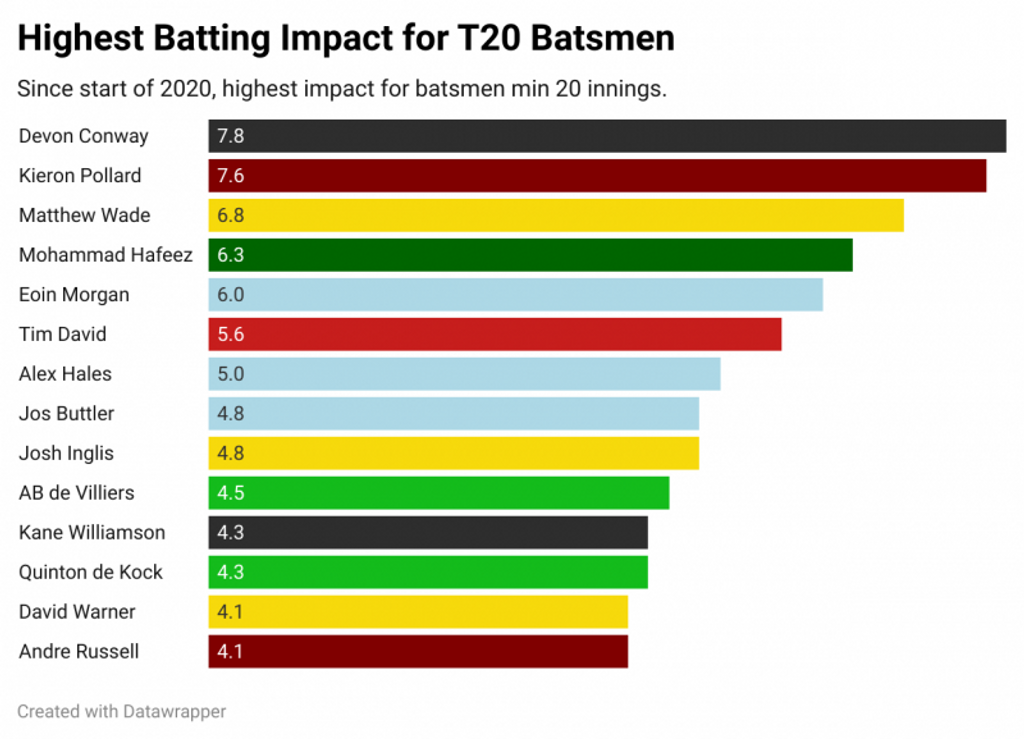

What’s more, the effect of those runs has been immense. Of the batsmen to play at least 20 innings since the start of last year, only a handful have a better Batting Impact than Hales, and the Englishman has played roughly twice as many games as the others. The sample is large, and very impressive. Against the best, Hales compares really rather well.

CricViz: Alex Hales has one of the best Batting Impacts in the world since the start of 2020

CricViz: Alex Hales has one of the best Batting Impacts in the world since the start of 2020

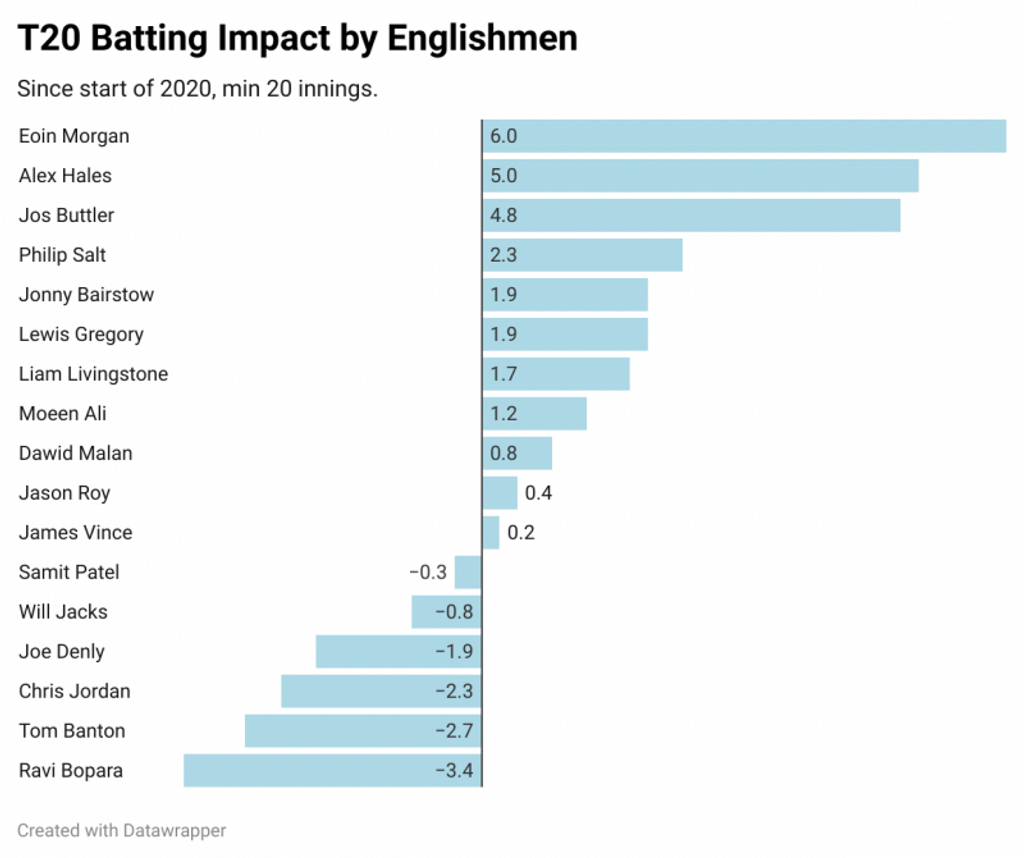

Bring it all a bit closer to home and Hales doesn’t suffer. Among Englishmen, only Eoin Morgan stands above him on the Impact chart since the start of last year, albeit from a much smaller number of games. Most obvious is that Jos Buttler, Morgan, and Hales himself are clear of the pack.

CricViz: Alex Hales is comfortable in England’s top three batsmen by Batting Impact since the start of 2020

CricViz: Alex Hales is comfortable in England’s top three batsmen by Batting Impact since the start of 2020

Hales has always been good, but he has rarely (if ever) been this good. So how has he reached this level?

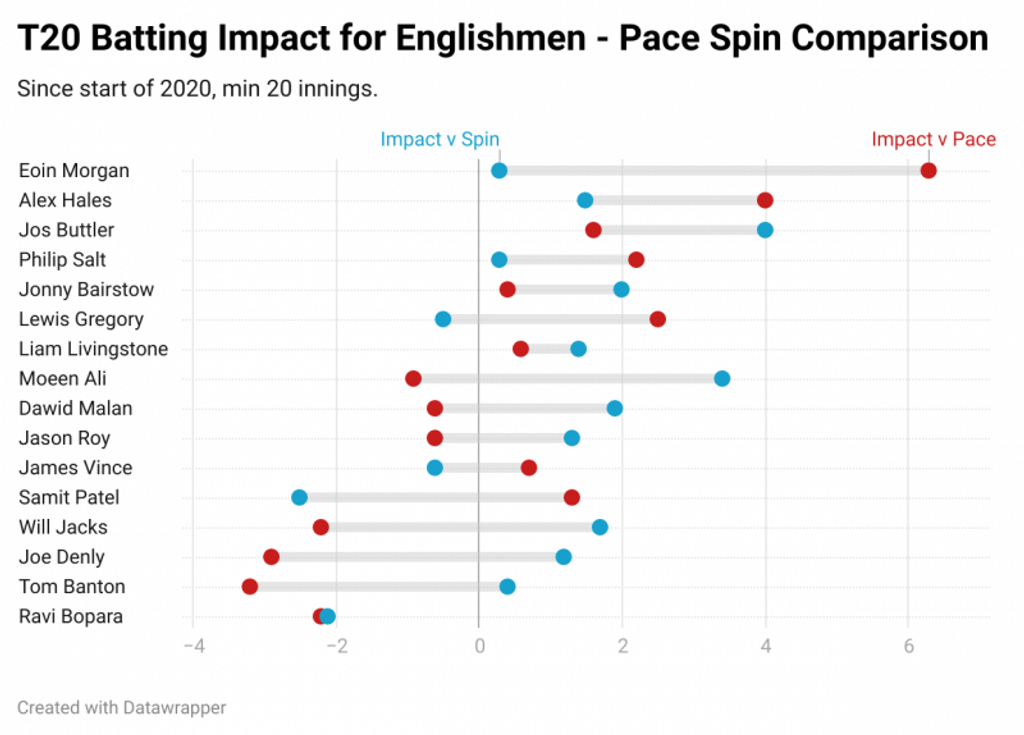

CricViz: Alex Hales has a significant recent positive Batting Impact against both pace and spin

CricViz: Alex Hales has a significant recent positive Batting Impact against both pace and spin

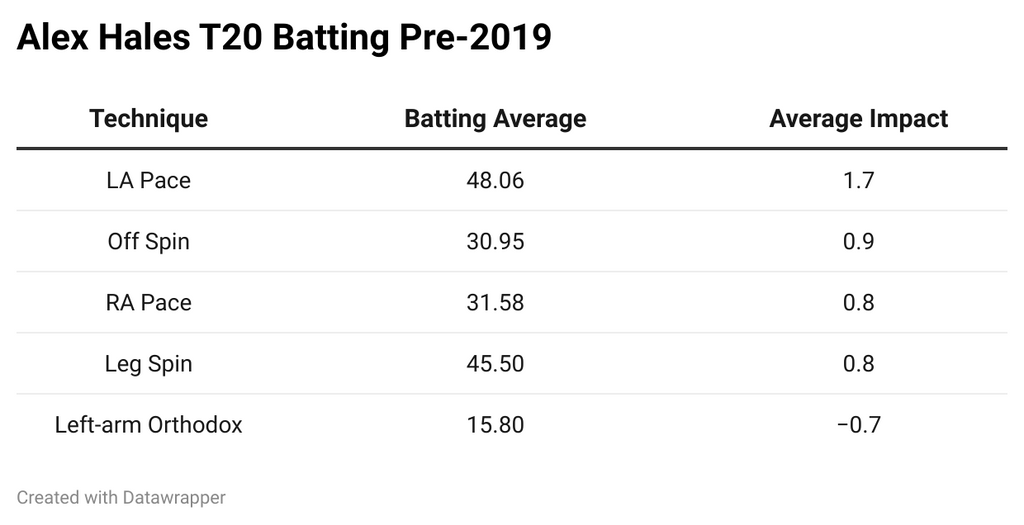

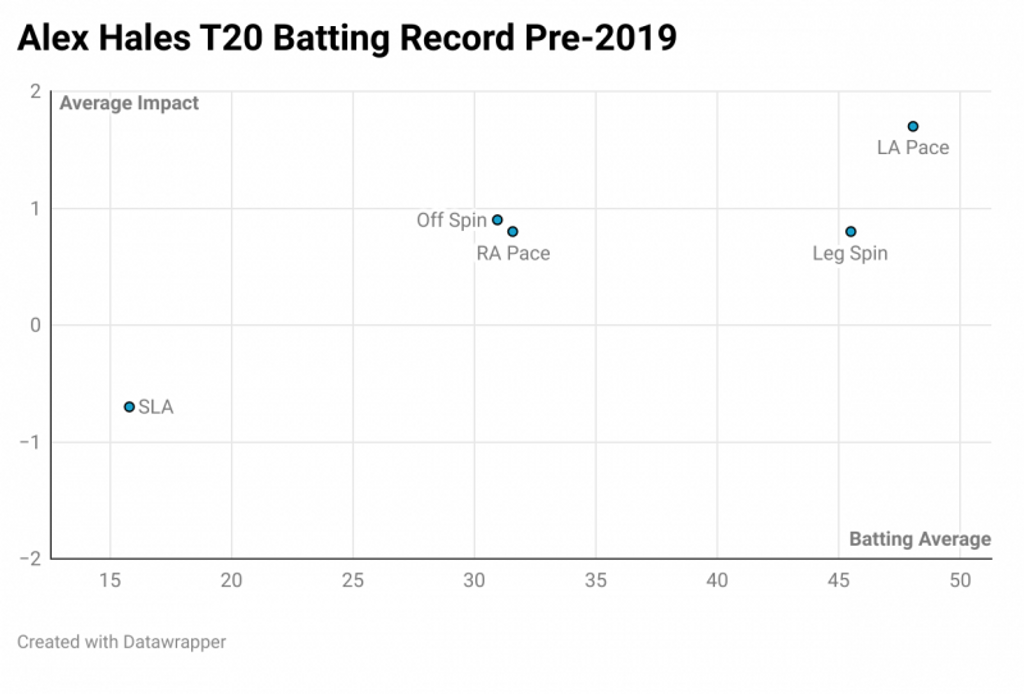

Well, it’s simple really – he’s improved the weaker parts of his game. In the first part of his career, Hales’ big weakness was against left-arm orthodox spin. Until the start of 2018, he averaged 15.80 against SLA (his lowest average against any technique), with a batting impact of -0.7 (the only bowlers he had a negative impact against). Any team even vaguely engaged with analysis and research would identify this weakness, target him with left-arm spin, and subsequently pop a low ceiling on what he could achieve.

CricViz: Before 2020, Alex Hales was held back by a weakness against left-arm spin

CricViz: Before 2020, Alex Hales was held back by a weakness against left-arm spin

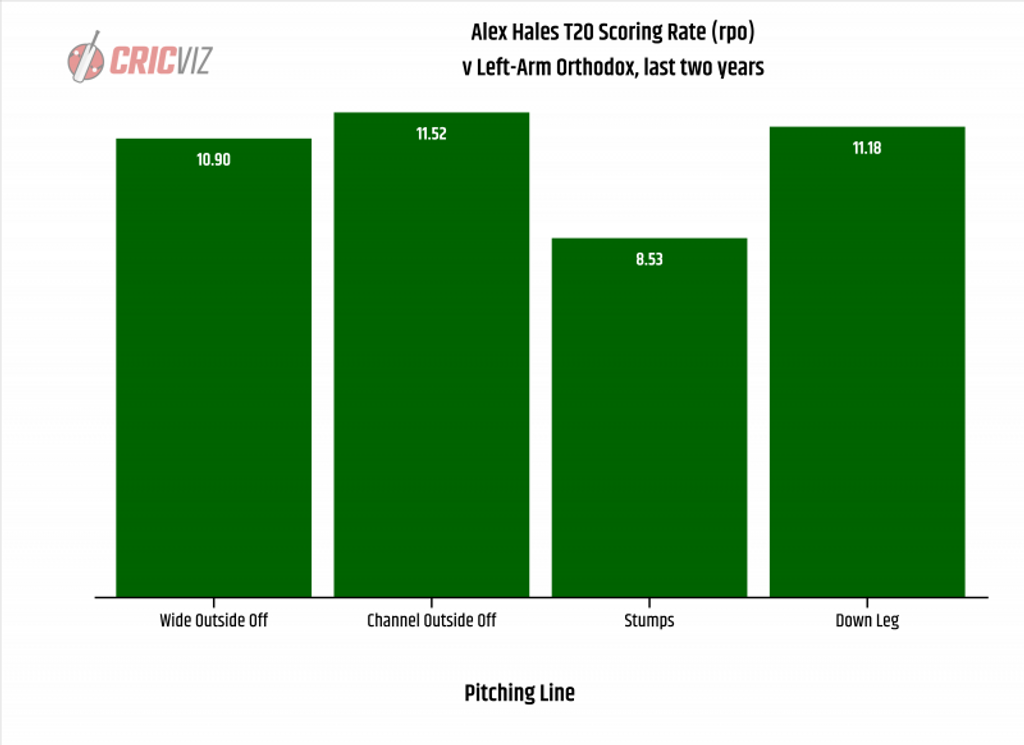

However, Hales has gone a long way to solving this problem. Since the start of 2019, he’s averaged 30.07 against left-arm orthodox, his average impact rising to +1.3. For this improvement in his record, Hales can thank a technical change.

Previously against SLA bowling, Hales stayed broadly in line with the stumps, keeping the whole field open to him; only 33 per cent of his runs against them were scored on the offside. Since the start of 2019, that figure has risen to 54 per cent, the majority of his runs coming through the offside.

Hales had learned to back away more and open up the offside, playing on (and exaggerating) his strength of hitting inside out. Previously, SLA spinners would see Hales as someone to attack with fuller, wider lines; in that early stage of his career he averaged 20 against full balls from SLA. Now he’s so adept at hitting those deliveries over the infield – averaging 69.50 against them in the last two years – that bowlers have had to go to more defensive lines and lengths.

CricViz: Alex Hales’ scoring rates against left-arm spin by line

CricViz: Alex Hales’ scoring rates against left-arm spin by line

This is all to say that the Hales we are talking about now is a different player to the one we last saw in England colours. And it’s not just obvious in these technical nuances, but in the part most obviously available to the naked eye – now, he starts his innings like a runaway train.

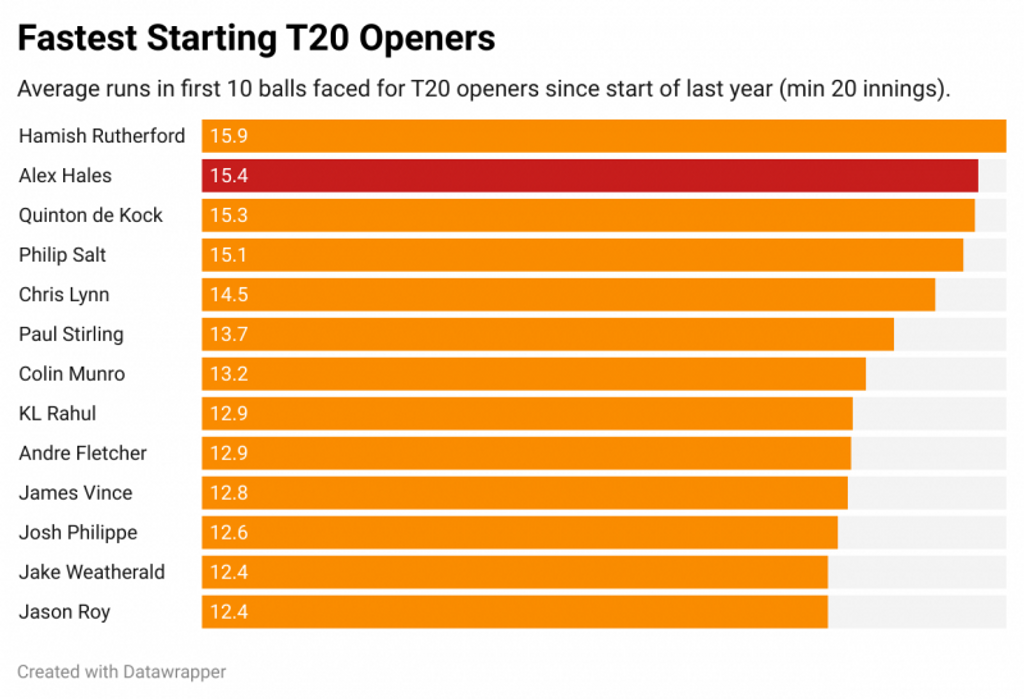

Hales has always been a player who loves batting in the Powerplay. At times he’s still been relatively cautious for his first 10 balls, getting set before kicking on, yet what he has managed to do in the last 12 months, either through a shift in mentality or simply through being in good form, is go hard from ball one. Since the start of last year, his scoring rate in the first 10 balls he faces is 9.23rpo, quicker than almost anyone else in the world. It forms a stark contrast with one of England’s incumbent top-order options Dawid Malan, a batsman who for all his statistical dominance, has consistently struggled to get off to fliers (averaging 9.4 runs in his first 10 balls for the last year).

CricViz: Only one opener has scored faster in the first 10 balls of their innings since the start of 2020 than Alex Hales

CricViz: Only one opener has scored faster in the first 10 balls of their innings since the start of 2020 than Alex Hales

And so, as the question of incumbents and selection issues comes into view, it’s worth restating that there really aren’t that many places up for grabs in the England XI. Jos Buttler is going to open; Jonny Bairstow looks set to bat at No.4, England exploiting his excellence against spin; Ben Stokes and Morgan will bat at No.5 and No.6; one of Moeen Ali or Sam Curran will set up at No.7. Almost to a point, everyone else – Malan, Jason Roy, Liam Livingstone, James Vince, Tom Banton, and Hales himself – is fighting for the two remaining places, an opening berth and a spot at first drop.

Among the prime candidates, it’s easy to see the appeal of each. Malan is left-handed, forming a nice contrast ahead of a tournament where spin and match-ups will be influential, and has been in excellent form, but given his domestic record he is arguably over-performing in England colours, and will likely regress; Roy offers white-ball pedigree, but is right-handed, and out of form. Hales’ own combination of superb form and rapid starts offer England a tactical weapon they don’t currently have at their disposal.

Except, of course, tactical considerations are not really the issue here.

The absence of Hales from the 2019 World Cup was extraordinarily close to costing England four years of progress and success. The injury of Jason Roy and his replacement in the side by the ever-beautiful but inconsistent James Vince left England weakened, and having to beat New Zealand and India to progress. Hales, with his six ODI centuries, would have been an upgrade on Vince. Whether you blame Hales for his own absence, or Morgan and Smith, is a question of judgement.

England are currently not selecting a player who is absolutely good enough to be in their first XI, on the grounds of off-field misdemeanours, and a loss of trust between captain and said player. Whether you agree with that, and with Morgan’s decision, is another debate entirely and one in which I am not hugely interested. If Morgan and Smith believe Hales’ presence in the dressing room is, in either a short or long term sense, detrimental to English cricket, then it would be wrong to select him.

However, the purpose of this article is to outline in as objective and straightforward a manner as possible, that Hales is top class. He’s not Buttler, he’s not Archer, but the congested strata of English T20 cricketers just below that absolute elite, includes Hales as much as it includes Ben Stokes, Adil Rashid, and perhaps even Eoin Morgan himself. What is without question, is that England are seemingly heading into a world tournament without one of their best players, with that player having been excluded on non-cricketing grounds.

Even if he is selected for the World Cup, England have already denied him the opportunity to play five matches in England colours in the conditions where the tournament will take place. Hales may get an IPL replacement deal, he may not, but that is out of England’s hands. England had the chance, with such an extended tour, to give a range of players experience in Indian conditions, in an England shirt. Hales receiving the chance to play any cricket in India did not remove the chance of another player to do so.

About that pre World Cup debacle, Stokes wrote in his autobiography that Hales was not “the level of player you could make an exception for”. It’s a pragmatic, and mature statement. To pretend that principles are not bent or twisted for the very best players is silly, and it’s a welcome admission from a current player that when it comes to the vagaries of ethics and ethos, the better you are the worse you can get away with. Good players don’t deserve special treatment; very good players do.

Unfortunately for some, Hales is putting up a superb case for falling into the latter camp.