Until the end of 2017, Joe Root had scored 10 hundreds from 35 home Tests at an average of 59.46. Since then, in 18 home Tests, he averages 33.93 with just one hundred to his name. CricViz analyst Ben Jones examines Root’s recent struggles in England.

In the last three home summers, Joe Root has made just one Test century. That was a ‘redemptive’ ton at The Oval during Alastair Cook’s farewell match, made at No. 4 in the order, away from the No. 3 position which has been the cause of so much angst. Yet in the last 18 Tests Root has played in the UK, this is the only century we’ve seen.

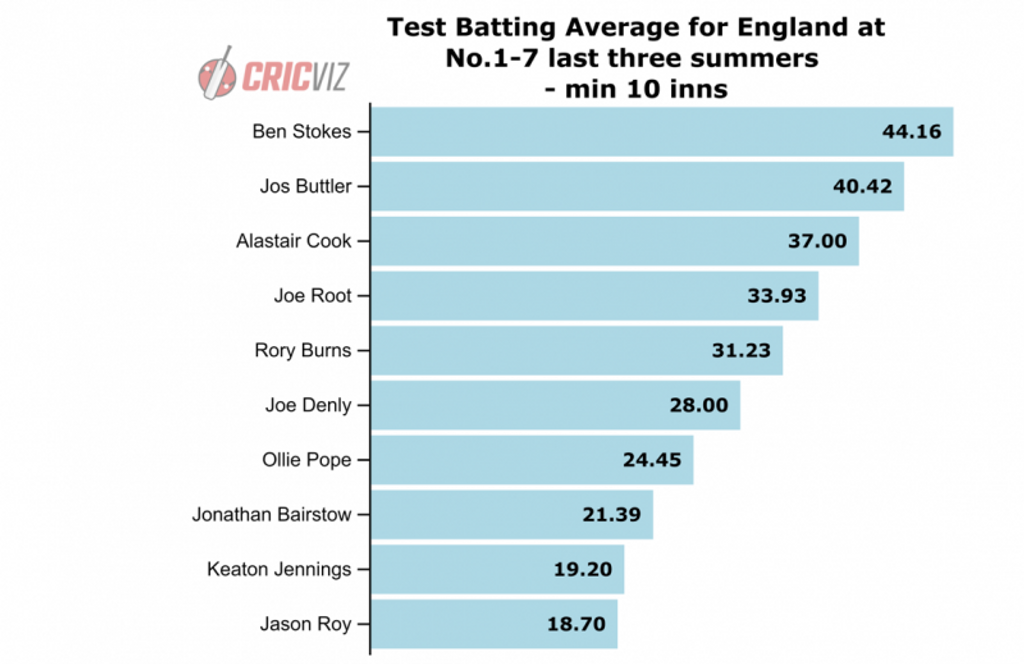

Root is unequivocally one of England’s best players, and only Ben Stokes has a reasonable claim on Root’s status as the best red-ball batsman. He has averaged 37.33 this summer, mediocre returns for someone of his ability, but there is no pressure on his place in the side, and nor should there be.

However, it’s interesting that a player as high quality as Root has found it so difficult to ton up, in familiar conditions, for quite a prolonged period of time. The rest of England’s top six have, on average, made an individual Test century every 19 innings in this time. For Root, the figure is 32.

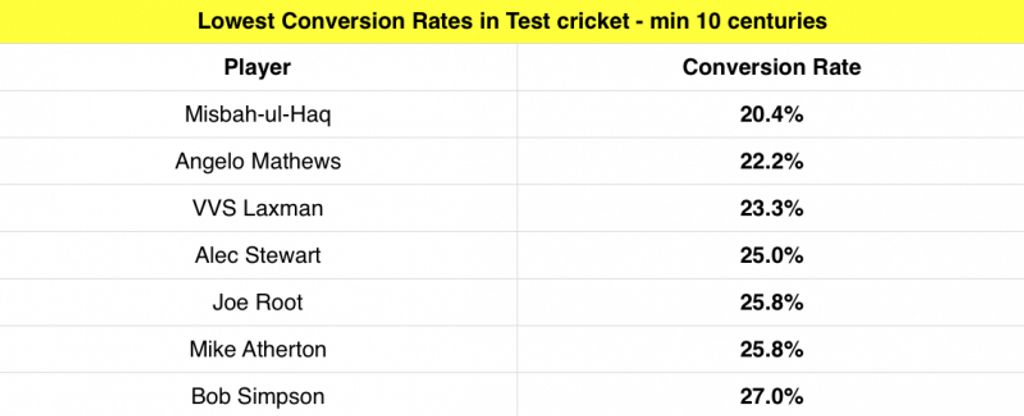

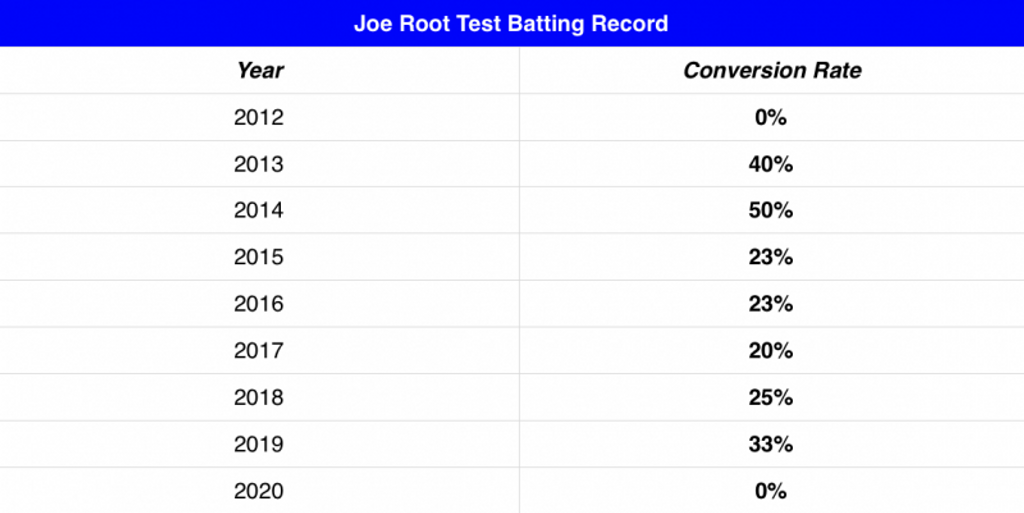

Root has passed 50 on eight occasions in these last three seasons, more often than any England batsman barring Jos Buttler. And yet, only once has he converted that ‘start’ into a century. Issues with conversion are nothing new to Root; with just 26 per cent of his 50-plus scores converted into centuries, Root is among the least effective converters in history.

What’s concerning for England, and for Root himself, is that despite starting his career with a real ability to make hundreds regularly, this is now a long-term pattern. Root’s problems surrounding conversion seem to be structural, rather than form-related. That fact that his average has never fallen far below 50 even with this issue, shows that there’s something a bit unusual going on.

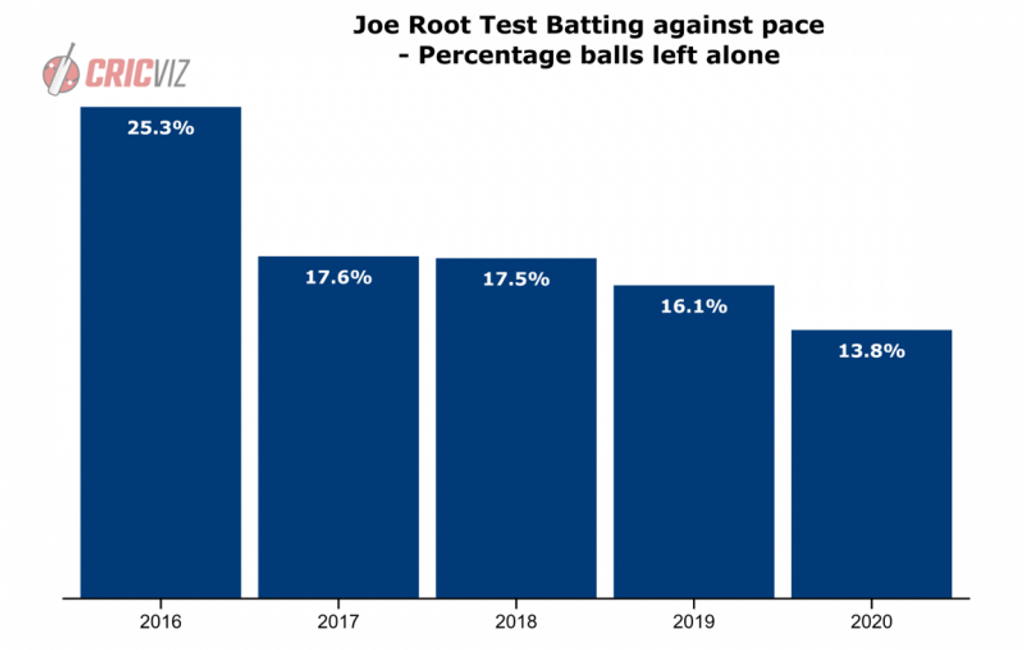

One reason for Root’s conversion rate is simply that he plays a lot of shots. His ‘busyness’, a clear quality in ODI cricket and broadly so in Tests, dictates that Root rarely leaves the ball alone. The average Test player leaves about a quarter of deliveries from seamers alone, but Root hasn’t hit that sort of figure in four years – and it’s a pattern that’s getting stronger. In each of the last four years, Root has left a lower proportion of deliveries than in the previous year.

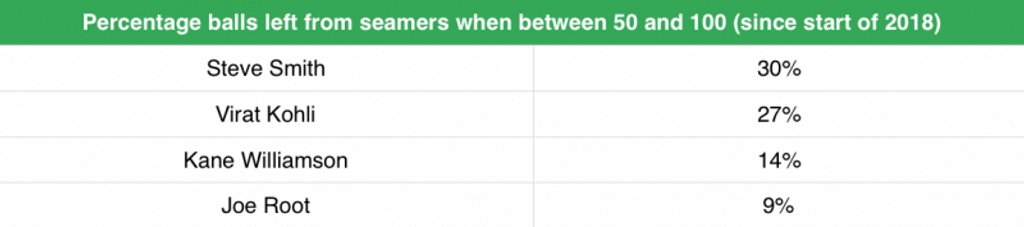

When compared to the elite, this is a real point of difference, because it’s a feature of Root’s game which really exaggerates after he reaches his half-century. After Root gets to 50, he’s playing a shot to 91 per cent of the balls he faces – for the best in the game, it’s a different story. Even when well set (i.e. having passed 50) Root’s false shot percentage hovers around 14 per cent, the average for all batsmen in Test cricket. Essentially, he never eliminates risk from his game, even when set.

Let’s also take things in the real perspective here. Steve Smith is arguably the best Test batsman of all time; Virat Kohli is a phenomenon; Kane Williamson is the best Kiwi batsman ever. Joe Root might not be as good as them. That is fine.

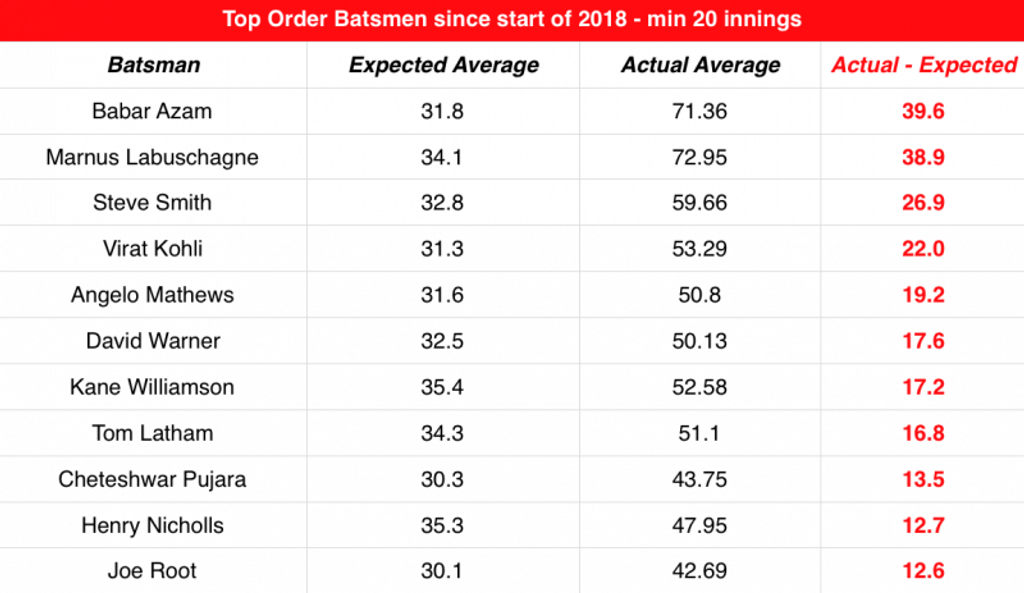

It’s important to note as well that, while Root’s aggressive approach may cause issues, he does face significantly better bowling than most players around the world. The deliveries bowled to him, in the last three years, would see a typical batsman average around 30 (according to our Expected Wickets model), and so Root’s record – averaging 43 – is still impressive. Part of the reason for that high quality bowling is that Root plays in such bowler friendly conditions, and that he is invariably coming in very early. One of those things is out of his control, and unlikely to change; the other is something England can improve.

If Joe Root wins four more Tests as England captain, which you’d say is a relative given, he’ll become the most successful – by pure volume of wins – England skipper of all time. The men ahead of him (Strauss, Vaughan, Cook) all have a lower win percentage than Root’s 52 per cent. Yet really, captaincy is one of the few things in cricket which can’t really be conveyed through numbers. It is a human role, one more related to managing personalities and mood than anything tangible, numerical, statistical. Root appears to have the unquestioning support of his team, his very young team, and that is hugely valuable.

With a few more pieces of the puzzle coming together this summer – a more solid opening partnership, a No. 3 who can delay Root’s arrival at the crease still further, and an increasingly large and varied battery of seamers – this is now a group of England players who suddenly look like a coherent team. Now he has that increased solidity in the batting order, you would hope that Root will be facing bowlers with a few more miles in their legs, and attacks who see him as one of a number of English challenges, not the sole threat.

In helping to create an environment where young batsmen can come in and succeed, Root The Captain has given England a huge boost; you hope that in coming series, Root The Batsman can benefit from the skill of those around him.