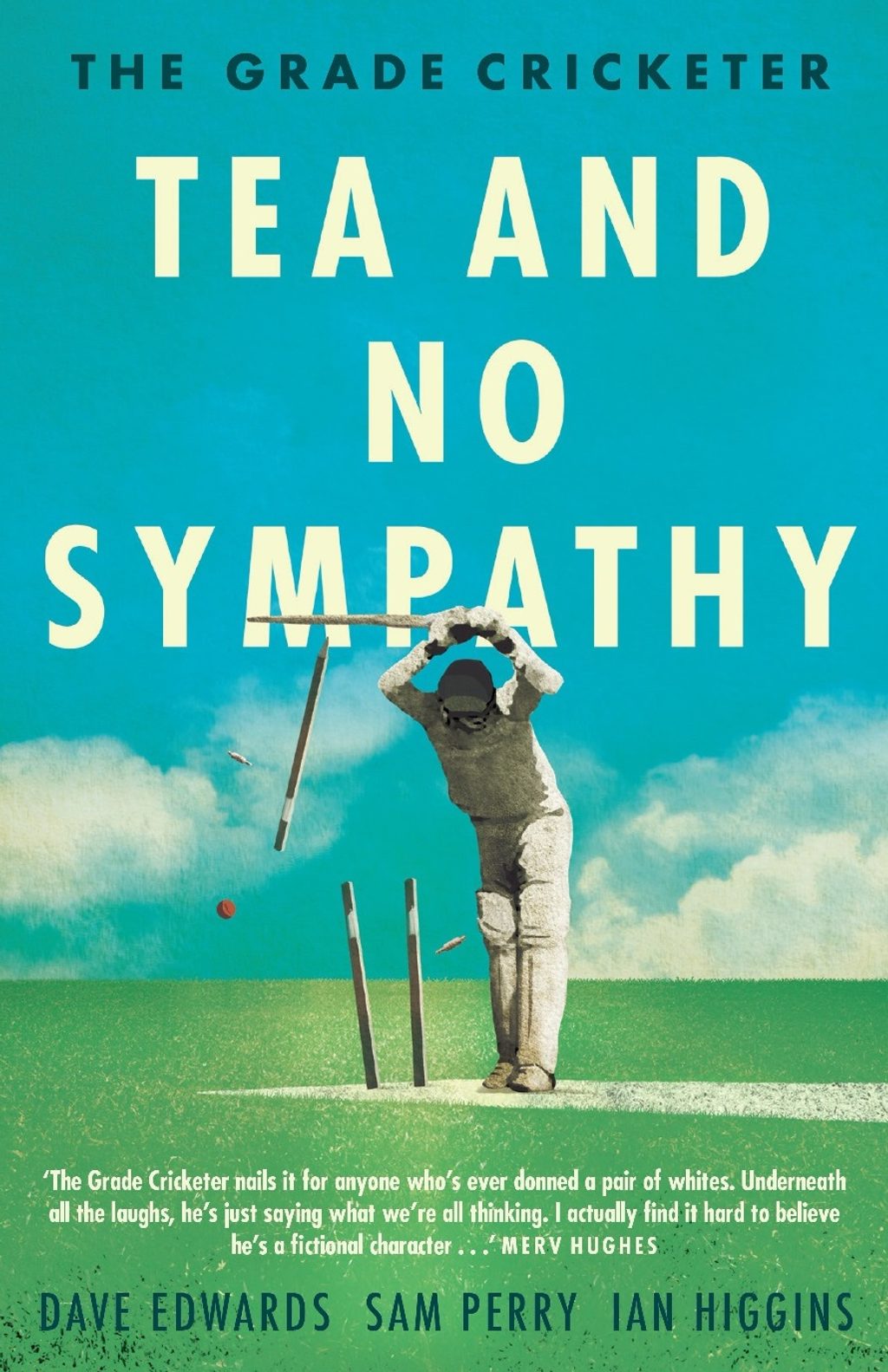

The Grade Cricketer is an Aussie publishing phenomenon, lifting the lid on a secret world of shattered hopes and dreams. In our extract from new book Tea And No Sympathy, our ageing hero gets the chance to escape his roots – as 12th man for the state side…

Adapted from The Grade Cricketer: Tea And No Sympathy by Dave Edwards, Sam Perry and Ian Higgins, to be published by Allen & Unwin on June 7 (£12.99). Extract first published in issue 7 of Wisden Cricket Monthly.

Nuggsy was good mates with our state player, Dessie Harrington. Dessie and Nuggsy had played juniors together – Nuggsy a bustling fast-medium bowler, Dessie an elegant top-order batsman – yet they’d paved divergent paths: one had gone on to play professional cricket for his state, the other had been secretly fixing grade cricket matches in order to pay off significant gambling debts.

Dessie burst onto the scene as a precocious 16-year-old, well over a decade ago, quickly earning a state call-up at the age of 19, bound for higher honours. As a young player of promise, I viewed Dessie’s swift ascent as hard evidence that a kid like me could make it.

A 1st grade match between Crib Point and Rye in Melbourne.

A 1st grade match between Crib Point and Rye in Melbourne.

Alas, Dessie was more like the cricketing equivalent of a busted IPO: his initial stock price surged upon breaking into the state side, whereupon he mustered a few daddy fifties in quick succession, but his market price dived after a couple of failures and he never managed to recapture that buzz. He was still a contracted player, probably on about 80 or 90 grand, but with bills mounting up and a kid on the way, he was starting to think about the next stage of his life. For athletes, once the thinking starts, it’s as good as over.

Another Saturday, another grim grade-cricket experience. Second day of a two-dayer – 8-1 overnight chasing 352-3 (declared). The suffocating familiarity of it all.

With 10 minutes left until the start of play, I felt my phone vibrate in my kit. To my surprise, it was Dessie.

“Hi, mate,” I answered. “Aren’t you playing today?”

“Nah, mate. I’m f**king 12th man again. They’ve asked me to go back to grade to have a hit.”

“Ah, f**k.”

“They need me to find someone to fill in as the sub. You want in?”

I gulped, unsure of whether this was a stitch-up. In these types of situations, the 12th man is asked to call up someone from his grade club to take over. So Dessie had chosen to contact me, a 31-year-old third-grader with hands like glass, to take his place.

“Don’t they want someone from twos at least?”

“Nah, they don’t care, mate. You should have seen the bloke we had for our last game. He could barely run in a straight line. Anyway, you said you wanted to know what it’s like to be a professional cricketer for a day, right? Here’s your chance.”

A million thoughts raced through my head as I stood at the door to the dressing room. An elderly man named Neville, whom I took to be some form of unpaid official, had escorted me from the car park. It hit me that I would be playing a game of cricket at the same ground that Bradman scored a Test hundred on.

Stand tall. Focus on your posture. Firm handshake. Solid eye-contact. You’ve got this, mate.

Neville stood in the middle of the room, cleared his throat, and announced in a thin voice that I would be replacing Dessie as 12th man for the day. I stood there proudly, waiting for a reaction, but no one was even listening. Graham Deakin, the veteran wicketkeeper, was describing his wife’s reaction to a fart he had performed in bed the previous evening. “It was so bloody filthy that it woke her up!”

Sheffield Shield Final match between Queensland and Tasmania at Allan Border Field.

Sheffield Shield Final match between Queensland and Tasmania at Allan Border Field.

A few moments passed as the team composed themselves, before ‘Deeks’ noticed me. “Hang on, are you from the Make-A-Wish Foundation or something?”

The coach walked into the room. He was a former state cricketer, highly regarded for his tactical thinking, recently mooted as a possible successor to the current Australian coach. Holding an open MacBook in his hand, he listened and nodded intently as the skipper gave his pre-match address. “Alright, lads, let’s have a big session out there.”

Perhaps it was the sensation of being in a professional dressing room but I couldn’t help myself. “Work hard, lads!” The entire room fell deathly silent. The whole playing group turned around to look at me as if I’d just dropped an insensitive racial comment. In some ways it was worse than outing myself as a racist. I’d just announced myself as a grade cricketer. Or even worse, a park cricketer.

“Work hard? That’s f**king grade cricket chat, champ,” the skipper chortled mirthlessly.

Eventually, the opening bowler had to go off for an injury check. Quite embarrassingly, he’d rolled his ankle fielding a ball that was gently padded back to him off his own bowling. “Get your spikes on, pal,” the coach yelled.

I sprinted into the dressing room and reached into my kit to pull out my cricket boots. I’d slipped them off with the laces still done up after the warm-up, which made it hard to put them back on. I tried to undo the knot by yanking one string, but this had the effect of creating an even more complicated knot, which I had no idea how to resolve. It was just like my old dream of getting timed out, only on a grander scale. “Hurry up!” the coach blared.

A couple of kids clapped as I sprinted down the tunnel onto the hallowed turf. I could overhear one of them say to the other, “Who is that guy?” “Fine-leg, champion,” the skipper yelled.

For the next five or six overs, I performed a fine-leg to deep mid-off rotation. There I was, isolated and alone, praying that the ball wouldn’t come my way…

A couple of overs later and I was called into action. The right-handed opener had skipped down the wicket, looking for quick runs, and launched our spinner down to deep mid-off. I saw it early and moved well as it sailed slightly to my left. The imaginary crowd roared in the background, but I kept my composure amid the pressure. I put my hands out with my fingers proudly up (the patented Australian way of catching a cricket ball) and held my breath. It stuck, like glue.

Some scattered applause emanated from the members’ part of the stadium. Perhaps six pairs of hands, maybe seven, but to me it felt like I’d just taken a Schweppes Classic Catch in front of a packed Bay 13 in 1992/93. I had expected to be wholly embraced by my new teammates, to fall into their arms – perhaps even be hoisted onto someone’s shoulders – but no one walked towards me. In fact, I had to sprint a full 80 metres to join the celebration circle, which had all the energy of a wake. There was nothing – well, not until Mad Dog broke the silence with what had become the common refrain of the day. “So, who are you?”

I looked over at the electronic scoreboard to see my name in lights, but the dismissal just read ‘caught (sub)’. Who was I, indeed? I felt like one of those seat-fillers at the Oscars, just plugging the gaps. Another couple of overs passed before I was summoned from the field. I had performed my duties to the required standard but now it was time for me to get the f**k off.

The coach ambled in, MacBook in his left hand. I could see an unfinished game of Solitaire on the screen. “You can leave now. Dessie’s on his way back,” he mumbled. “Who are you again?’ he asked, this time with a smile on his face, conscious that this sentence had become a running joke.

I began to answer, but he started shuffling out of the room the moment my mouth opened.