Phil Walker reports from Melbourne as England do battle with a phenomenon.

Smith seems intent on resetting the parameters of modern batsmanship

Smith seems intent on resetting the parameters of modern batsmanship

VIEW SCORECARD

Here at the Melbourne Cricket Ground, where the pageant first began 140 years ago, you can’t move for history. Outside, huge bronze monsters of Australian sport pockmark the coliseum concourse. Over there you’ve got DK, captured for eternity in mid-delivery-stride; and down the way, outside the stand named after him, old Bill Ponsford; then of course there’s Shane – well at home among the Aussie Rules boys who share this stage; and, though it barely needs saying, the omnipotent accountant, toe of his bat pointed forever skywards. Inside, the walls are lined with paintings and prints of touring teams from the heart of the eighteenth century, to photographs of more recent iterations. This is, as ever, history as told by the victors.

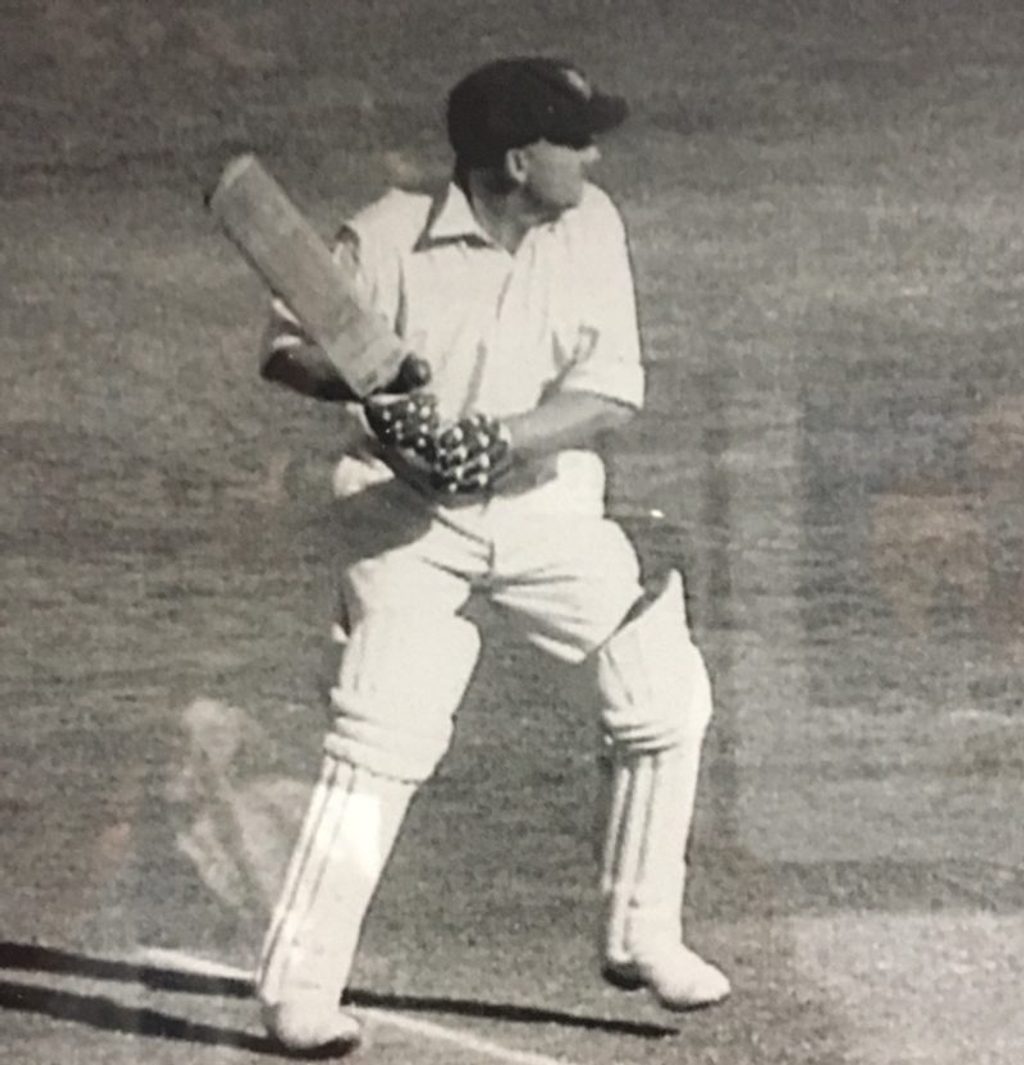

And there, again, we find Bradman; you can’t move for the bloke. At one point, in the MCC pavilion, you alight on a sequence of five still photographs contained in a single frame, capturing the full unfurling of an off-drive from his 270 in 1937 – an innings considered by Wisden in 2000 to be the greatest of the century. (Constructed on a drying wicket after a thunderstorm, and made from No.7 so as to have avoided the worst of the conditions, it was, wrote Cardus, “congealed labour”; it was also his strategic masterpiece.) The first photograph of the five, capturing the initial gather of Bradman’s ‘rotary’ backlift with its arc out towards gully, would be rousing enough. Except that these days the image is doing something else, something extra: and what’s happening is causing us to look anew. Because 80 years on from that shot, outside in the middle – where England fought so hard today that you could have bled and cried with them just sitting here in the stands – the 88,178 patrons packed into this place saw Bradman’s true son and heir going about his business.

Steve Smith’s figures, while not quite Bradmanesque, are creeping up past all pretenders into second place. We know that he’s averaging 74 for the calendar year, and, staggeringly, 94.37 in the first innings of his 60 Tests to date. And now we know that his life, whether by design or fate or subliminal intuition, has been spent honing a technique that carries visual and rhythmical echoes of The Don’s perhaps more purely than any other batsman. Though it may not be a thought that England’s cricketers, supporters and fatalists are particularly keen to dwell on, it’s a fact nonetheless: we are witnessing something extraordinary, a run of sustained runscoring that may eclipse all others; all others, of course, bar one.

Bradman’s ‘rotary’ technique has been absorbed by Steve Smith

Bradman’s ‘rotary’ technique has been absorbed by Steve Smith

With most players, they will offer you a chance or two on their way to establishing an innings. Smith offers the chance of a chance. Nothing more. He joined the scene today in the afternoon session, in the midst of a surprisingly robust comeback from England’s bowlers, dragging them back after a one-sided morning. The score was 135-2, and implausibly, the strangle was on. Much as Smith had been ostentatiously watchful at the Gabba en route to 141*, so he was again today. Though on a human level, respect between these two teams appears to be in ever-shortening supply, there is plenty of it kicking around between them as cricketers – plenty more, in truth, than either care to admit. Australia would lose two wickets in the afternoon, and scavenge just 43 runs.

And yes, England did beat Smith’s outside-edge once either side of the tea-break, and once again with the new ball. Three legitimately false shots. If a tickle had been secured to any of them, England would have felt like this was a day worth having. And how they kept at it. To restrict Australia to 244 from 89 overs in searing heat, with a raucous crowd up for a laugh and a 3-0 scoreline slapped on their foreheads, was a mildly herculean effort.

Warner and Curran exchanged words in another heated afternoon session

Warner and Curran exchanged words in another heated afternoon session

After the horror of that morning session, dominated by David Warner, who went to the break 82*, all the seamers – exploring the very farthest edges of their right-arm-over, 133-136kph demographic – bowled their hearts out. Bowling dry, hanging it outside the off-stump, refusing to buckle or cave, the effort was spearheaded by Tom Curran, whose skills and accuracy slotted in naturally next to Anderson’s.

Tom Curran on debut was one of England’s bright spots

Tom Curran on debut was one of England’s bright spots

Warner, so riotous in the morning, was becalmed after lunch, and on 99, Curran thought he had him when Warner miscued an attempted pull to be taken at mid-on, only for the big screen to confirm that Curran had overstepped; a guttural schadenfreude duly drove the biggest roar of the day, as Warner sauntered back to the crease. Curran is still waiting for his first Test wicket, but it will come. He is 22, smart, and he knows his game. He bowls one side of the wicket, has a canny array of cutters and slowies, enough pace to keep good players honest, and if the approach to the wicket lacks a little of the Anderson groove, the action itself is robust, and encouragingly linear; though he has only been a professional for four seasons, he has racked up a lot of consecutive cricket, with 171 first-class wickets from 51 games. It looked like a sensible selection here, and it has proved to be so.

Curran and England have a new ball three overs old to play with in the morning. Irritatingly, they also have to contend with a phenomenon.