CricViz analyst Ben Jones picks apart the brilliance of Australia’s two spearheads.

For every ‘Fab Four’, there’s a Lennon and McCartney.

Australia’s attack has, over the last few years, been a relatively stable affair. The established quartet of Mitchell Starc, Pat Cummins, Josh Hazlewood and Nathan Lyon were the backbone of the side, even as batsmen came and went with relative frequency. It’s rare a bowling unit is so consistently selected that they get a nickname, almost a brand, but The Fab Four were afforded just that credit.

Yet this series, they’ve been broken up. For the first time in a while, Australia have had those four bowlers fit and available but have opted against selecting their most tried and tested unit. Until this Test that is, and for a while it looked like a mistake.

Mid-afternoon today, the game was drifting. Nathan Lyon was bowling too straight to Joe Root, allowing him to nurdle and accumulate with far too much ease on a turning track. Mitchell Starc was spraying it about, unable to get his radar right on a pitch where inaccuracy was always going to be punished.

England were batting through the precious time that Australia need to force victory. The draw was favourite with WinViz, and it looked increasingly like rain was going to have a greater influence on this match than any one player. Then, shortly before tea, Tim Paine threw the ball to Pat Cummins.

Cummins’ spell, which started with three overs before the interval and then followed up with seven more after, was a colossal effort. He has never bowled as many overs on the trot in a Test innings, saving his moment of peak stamina for an Ashes Test threatening to wander away from Australia on a flat deck, with a four-man attack if not crumbling then beginning to creak.

What’s more astounding is that this wasn’t a spell of third gear, line and length trundling. It was accurate, of course, but this was a spell of fiery, top-gear fast bowling. An average speed of 139.74kph across those ten overs made it the fastest spell by an anyone other than Starc in this Test. Backing that accuracy and pace up with considerable movement off the deck (an average of 0.89° of seam movement, well above the match average) made it almost unplayable.

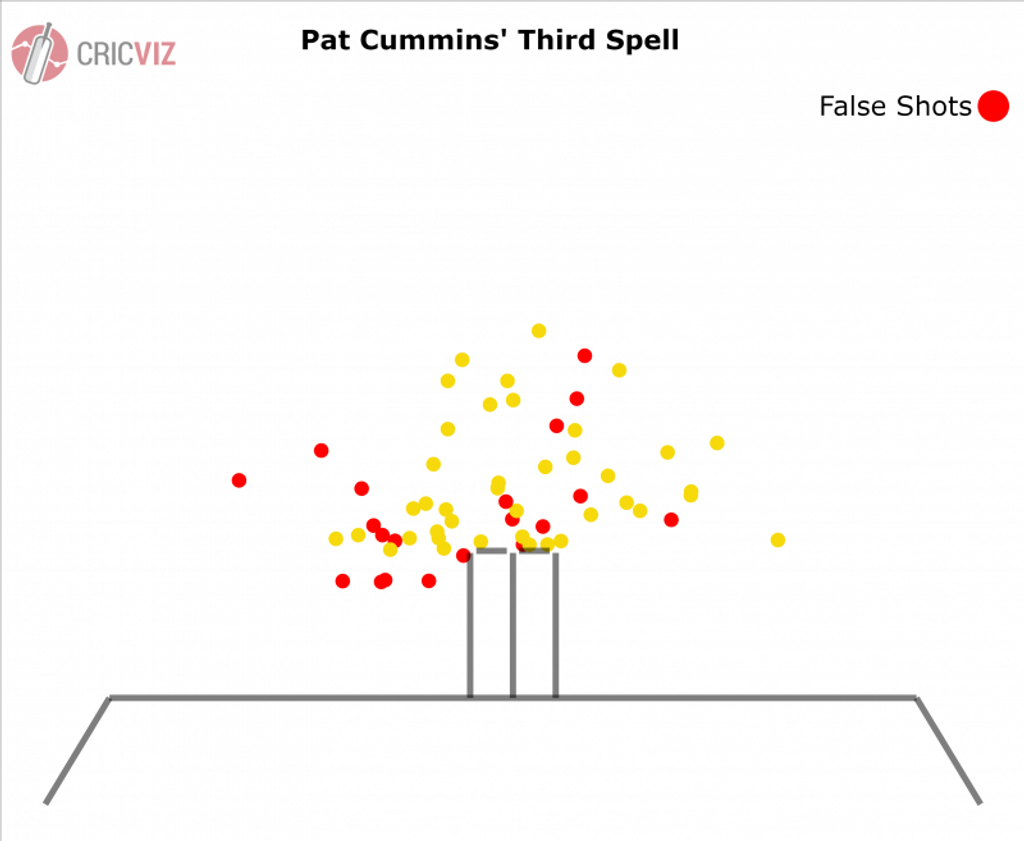

And so it seemed to England’s batsmen. In that 60-ball period, he forced 20 mistakes from Root and Rory Burns, a third of his deliveries bringing an edge or a miss. The ball was leaping off the splice of Burns’ bat and looping into gaps, and when it wasn’t, the ball was flying past the edge. At no point did either Root or Burns look comfortable, and they were both absolutely set having batted all day. Cummins was making it look like they’d just walked out to bat.

And yet England almost got through it. Somehow, the onslaught from Cummins wasn’t enough to bring the breakthrough; he had hammered away at England and, for all his effort, got nothing. Eventually, Burns couldn’t keep out a sharp short ball, but not one from the hand of Cummins.

The issue for England was that off the back of this onslaught, rather than there being a collective reduction in pressure, Australia came again. Their best bowler, Hazlewood, came and pushed at the open door – or rather, ran at it with full force.

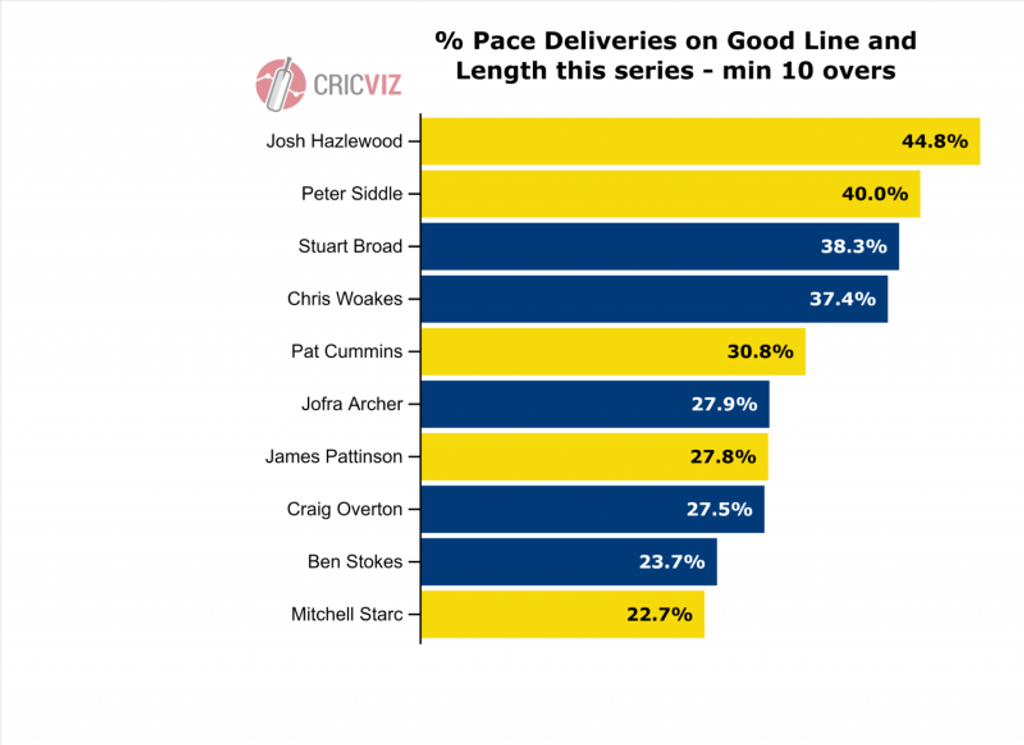

Across this series, Hazlewood has pitched 45 per cent of his deliveries on a good line and length. He doesn’t mess about. If you’re a batsman – particularly a right-hander, particularly one called Jason – then he’ll be at you, from the get-go. As a bowler, he’s more than capable of getting you out with pressure alone, the cumulative suffocation of good ball after good ball. Rash shots follow, bad balls get wickets. We’ve seen it too many times to mention.

Yet today, he didn’t need to get wickets with the bad balls, because at the end of this outrageous cumulative pressure created by Cummins, he simply produced two absolute jaffas to remove Root and Roy. The first had a Wicket Probability of 33%, the second 32%; they were the two most dangerous balls he bowled all innings.

With the light beginning to dim, the pressure on England heightening as the follow-on target became a more pertinent topic of conversation on air and in the stands, Australia’s attack leader unleashed two savage, missile-like full balls that would be good enough to take a wicket at almost any moment. Given all that had come before, Hazlewood could have burst England’s balloon with a pin. He opted for a machine gun.

There has been a lot of discussion around the selection of Australia’s seamers this summer. The deliberate tactical choice to try and “bowl dry”, limit the scoring of the opposition through accurate, slightly more defensive bowling, has been enough to keep Starc out of the side up to this point. The injury record of James Pattinson has been a hurdle to get over, albeit one identified well in advance. Peter Siddle has been a noble foil, and has completely performed his role as assigned, but has at times looked a little lacking in terms of penetration. Each of the likely support bowlers has had a mark against their name, some bigger than others.

What we saw today was that, ultimately, it’s Cummins and Hazlewood who are the beating heart of this Australian attack. Their skills, versatile and durable in all conditions (as far as we can see), are strong enough that the call on that third seamer is not as pressurised as it could be. They bang away in the corridor outside off, they get just enough movement through the air and off the pitch but are, in no way, reliant on that movement.

The luxury of being able to pick and choose horses-for-courses backup bowlers is testament to Australia’s quick bowling depth, but Cummins and Hazlewood stand far and away above the rest, and with them in the side Australia will, barring disaster, rarely need to rely on the others. When the vocals are as perfect as this, you don’t worry who is on drums.