As the Pakistan Super League continues to be dominated by sides batting second, Ben Jones considers some reasons for this ever-increasing trend.

Ben Jones is an analyst at CricViz.

Credit – PCB

In a climate where for numerous reasons cricket has not been top of the agenda, this Pakistan Super League season has been quietly intriguing.

On the surface, this may not appear to be the case. The quality of the action itself has been solid, if not spectacular; the matches entertaining, if not thrilling; the race for qualification competitive but softened a little by the under-performance of the Multan Sultans. But beyond this, there has been a developing trend that, in the truest sense of the word, has been historic.

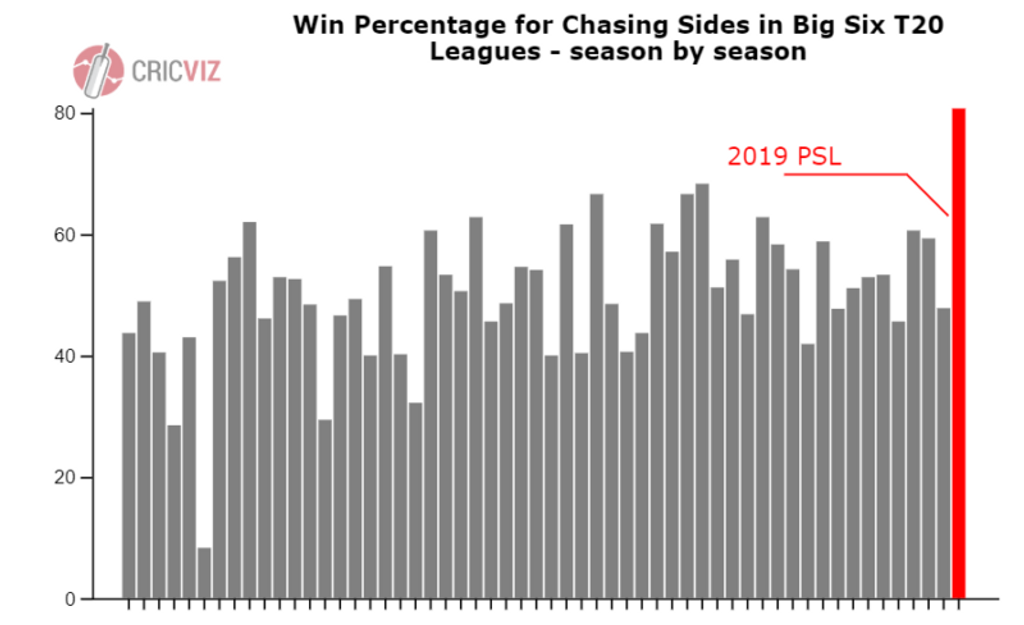

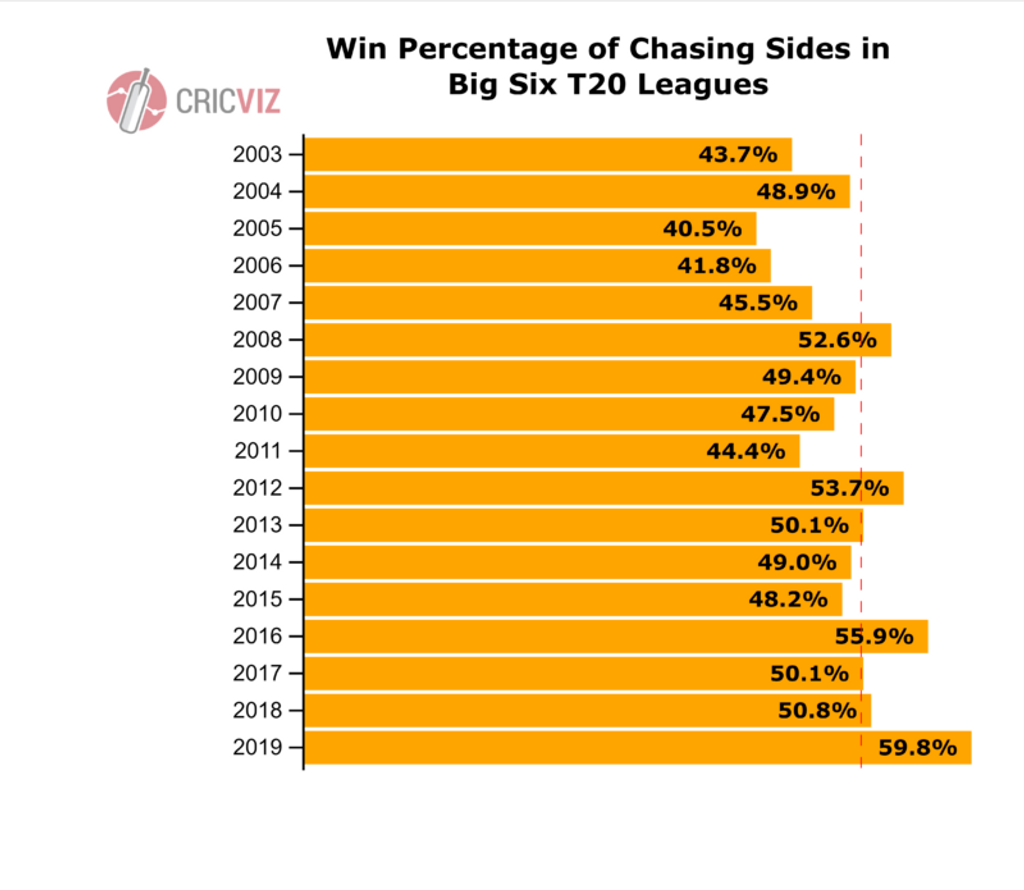

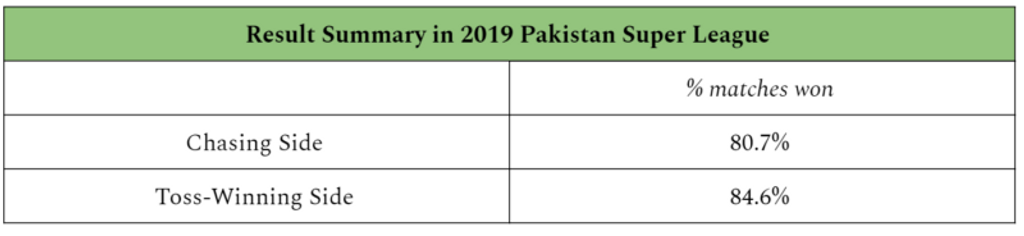

As it stands, 81% of matches in this PSL season have been won by the side batting second. Among the six major T20 leagues (Bangladesh Premier League, Big Bash League, Caribbean Premier League, Indian Premier League, Pakistan Super League, Blast), that’s the highest figure for any individual season – ever.

Of course, this does reflect a wider trend in T20 cricket. Chasing sides have found increased success in recent years, as many have noted and many more have lamented. However, that improvement has been gentle and gradual, subtle improvement in the chances of chasing sides over time. Yet whilst the past seven years have seen an evolution in the balance between chasing and defending, this season’s PSL has been a revolution.

Captains aren’t missing this trick. There have been 26 tosses so far this season, and only once has the captain who called correctly opted to bat first. 25 out of 26 times, the toss-winning captain has looked up, looked down, looked at the opposition, and decided to chase.

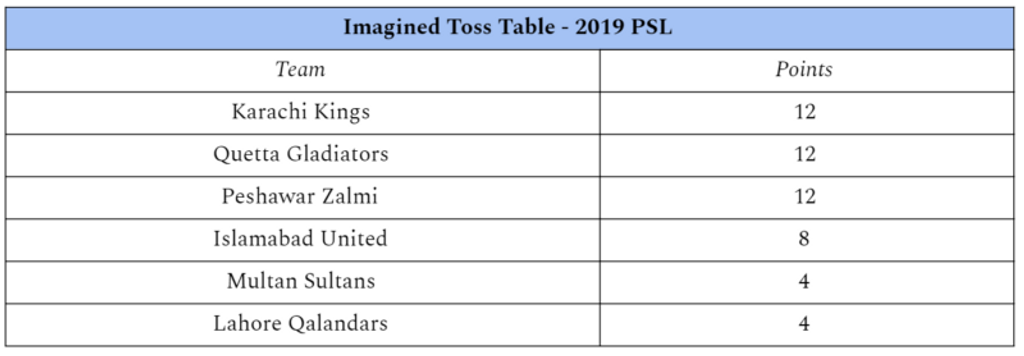

It has created a slightly concerning bias in favour of the toss-winning side. If the tournament had dispensed with cricket altogether, and simply allocated two points for a won toss, the table would look awfully similar to the actual tournament ladder. The order is slightly altered, but the same teams would be heading through the knockout rounds. Of course, that isn’t ideal.

Yet as with everything in cricket, this has caused a fair degree of angst. People have offered solutions ranging from the removal of the toss to penalty runs for the chasing side, the difference in chance of victory too focused on the toss of a coin – or the flip of a bat.

It’s only natural that fans push back against a trend which threatens to make the most unpredictable form of the game more monotonous – but rather than worrying about the effect, it’s more interesting to ask why this trend is occurring.

What outside influences have been acting on the game to force this change, and where has it been felt most keenly?

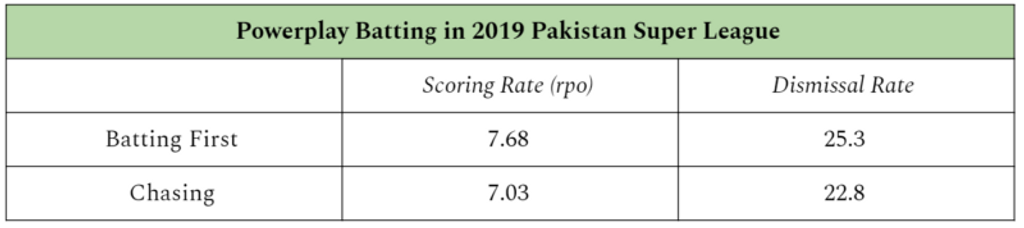

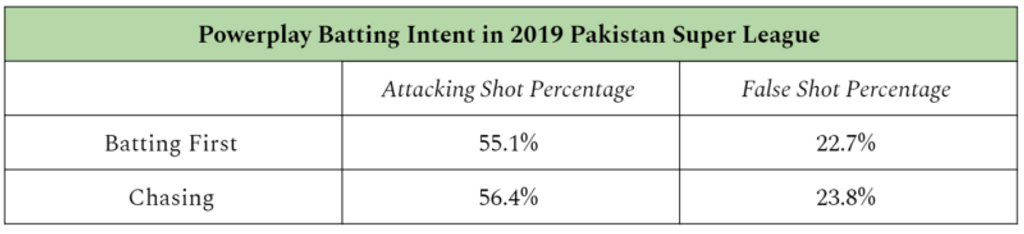

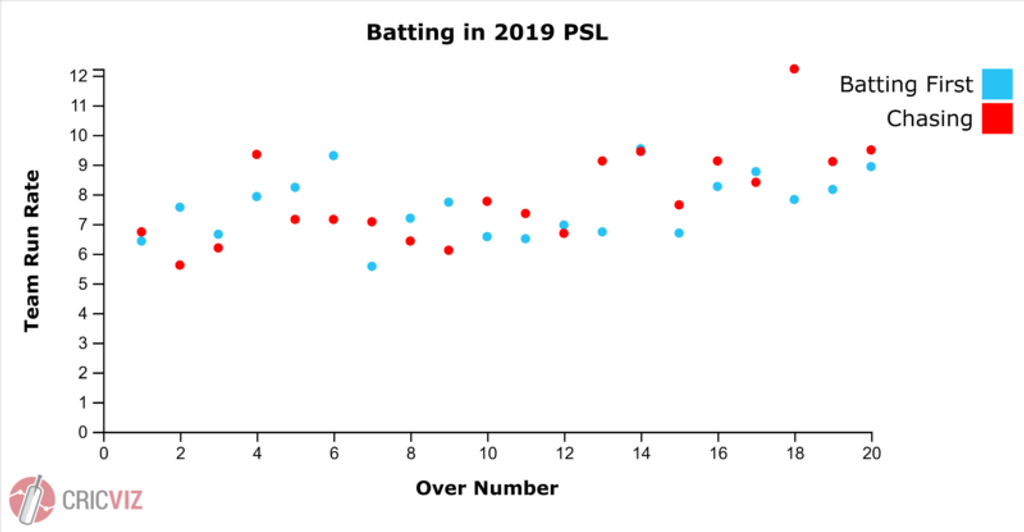

Well, the difference doesn’t seem to be coming in the Powerplay. Chasing sides are actually performing significantly worse in the first six overs, scoring more slowly and losing wickets more regularly compared to sides batting first. It isn’t fair to attribute their slower scoring rates to a consciously more cautious approach; chasers have attacked slightly more than sides batting first, and with slightly more risk.

Given the impact we all know that the start of the innings has on the rest of proceedings (heaven forbid you lose three wickets in those first six overs), it feels intuitive to suggest this is where chasers are establishing their massive advantage. But that isn’t the case.

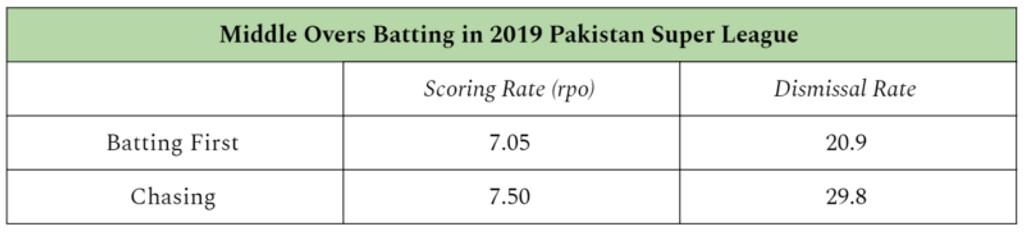

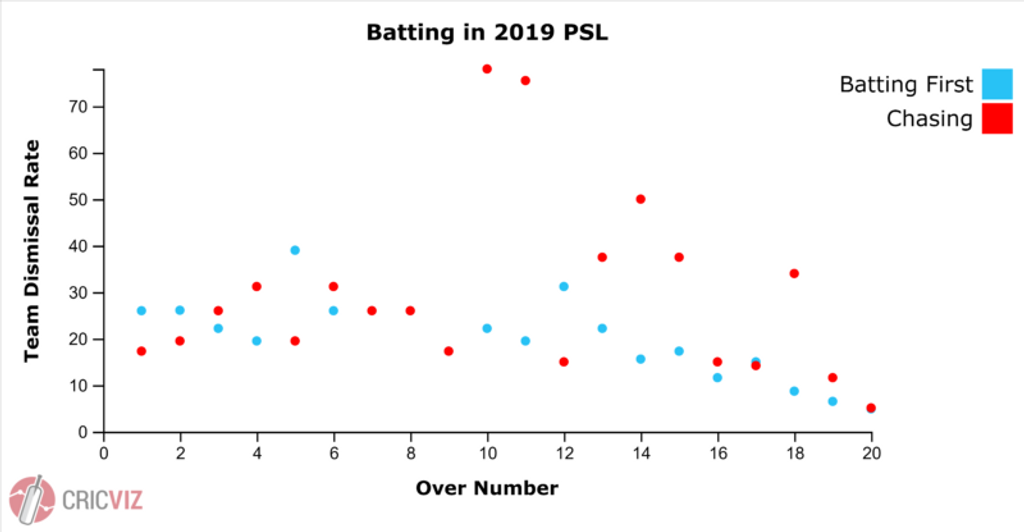

No, the first time in the innings we see a real gulf start to widen between sides batting first or batting second is after the Powerplay has finished, because in the middle overs it’s a different story. Whilst scoring rates for both sides remain relatively close, dismissal rates suddenly diverge. Sides batting first have lost wickets with alarming frequency, whilst the chasing sides have managed to remain stable.

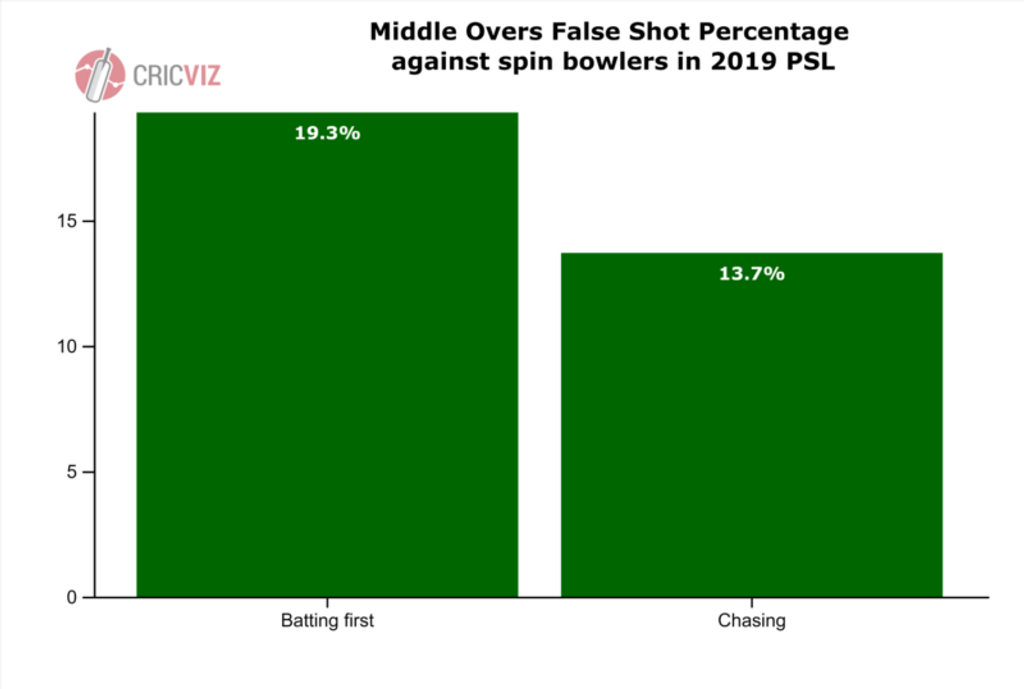

This pattern is particularly clear against spinners. In overs 7-15, sides batting first have lost a wicket every 19 balls against spin; for sides batting second, that’s a wicket every 29 balls. That is a huge gap. Chasing sides play with significantly more control against the slower bowlers, hitting more deliveries to the boundary and accruing fewer dot balls.

It’s affected even the best performers. The four leading spinners (in terms of wickets taken) this season have been Umar Khan, Mohammad Nawaz, Sandeep Lamichhane and Fawad Ahmed, but the bulk of their wickets have come in the first innings. Their combined strike rate in the first innings (15.3) is significantly worse than their strike rate in the second (21.0). The best bowlers in the competition have been unable to exert the same pressure when defending a total as they have when limiting a target.

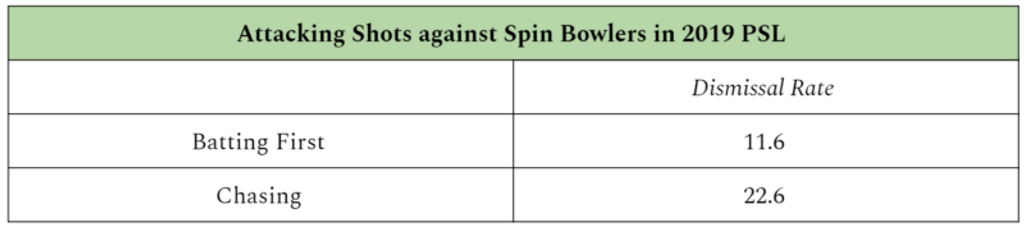

There are other moments where batting against spin appears to be an area where chasing sides have held an advantage. The attacking strokes that are played against spin are much, much more secure in the second innings. An attacking shot against spin in the first innings is almost twice as likely to lead to a wicket as an attacking shot in the second innings.

However, for all this, the difference in scoring rate in that middle period wasn’t that significant. 0.45rpo is a reasonable difference, but it’s not vast, and certainly not accountable for 81% of chasing sides coming out on top.

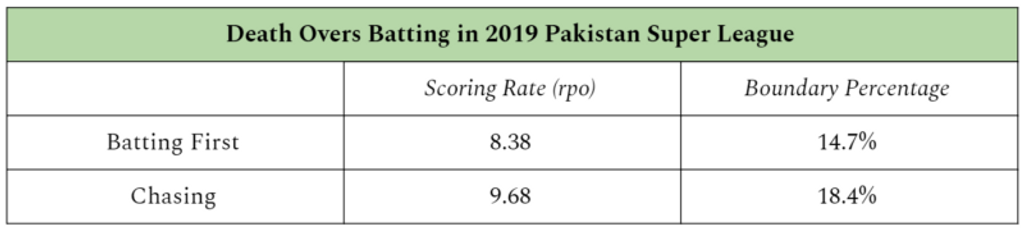

However, the natural consequence of losing more wickets in the middle overs is that teams batting first can’t accelerate as well at the death, and this has undoubtedly been the case this season. With more wickets in hand going into that climactic period of the innings, chasing sides are able to score significantly more quickly, largely through hitting more boundaries.

So the main factor in the dominance of the chasing sides, from what we can glean from the numbers, is that middle overs wickets have cost sides batting first dearly.

This effect is then amplified by the lower scores that we have seen throughout the tournament. The high-quality of the bowling attacks, and perhaps the relative weakness of the domestic batting options, have contributed to a scoring rate of just 7.68rpo across the tournament – the slowest scoring rate for any major league season since the 2016 BPL.

It’s important to give some credit to the bowlers in this. The Expected Run Rate (Tracking Only) for this season is 7.01rpo, the lowest figure for any PSL season. What this suggests is that regardless of the batting, the defensive quality of the deliveries has been extremely high. This naturally drives scores down, removing the psychological barrier of massive totals, making it easier to chase.

More broadly, T20 leagues developing unique characteristics is a good thing. The reputation of the PSL as a bowlers’ tournament is great, and offers texture and variety to the domestic calendar. Perhaps the effect of this is that chasing will continue to be more prevalent in the PSL compared to other leagues – the natural effect of that will be that teams scramble to reverse that trend.

As teams try more specifically to counteract it, the trend will likely disappear. However, for now, the PSL is a chaser’s paradise – so watch that coin closely, chaps.