CricViz analyst Ben Jones examines the key reasons for England’s defeat in the first Test against West Indies, in particular the struggles of their quicks to find the swing they often rely on.

Why didn’t it swing in Southampton?

This was a curious Test, for many reasons. The fact it was the first match after a pandemic is the most obvious. The biosecure environment, and absence of the crowd another unavoidable aspect of cricket’s New Normal. However, there was another quieter element in play this week, one that made this Test rather more unusual. It was a Test in England where the ball didn’t swing.

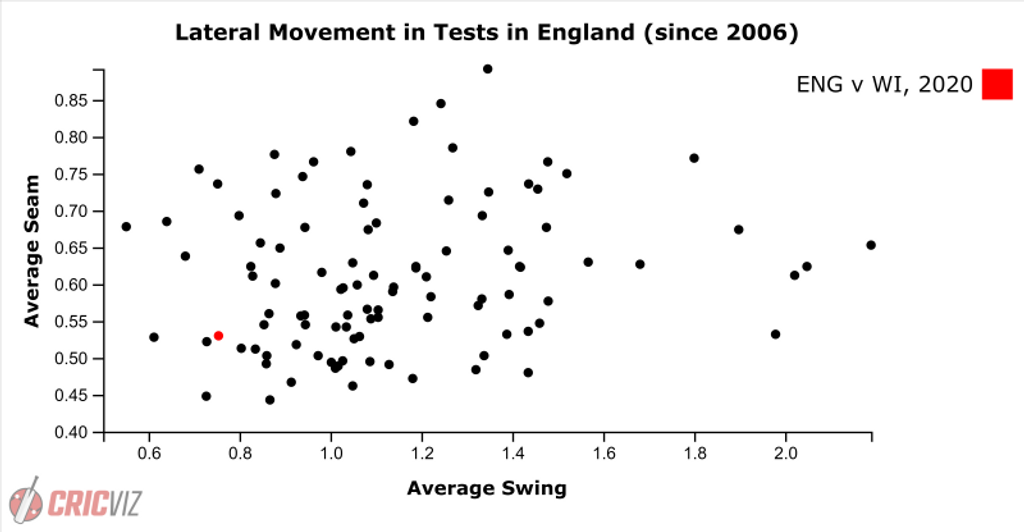

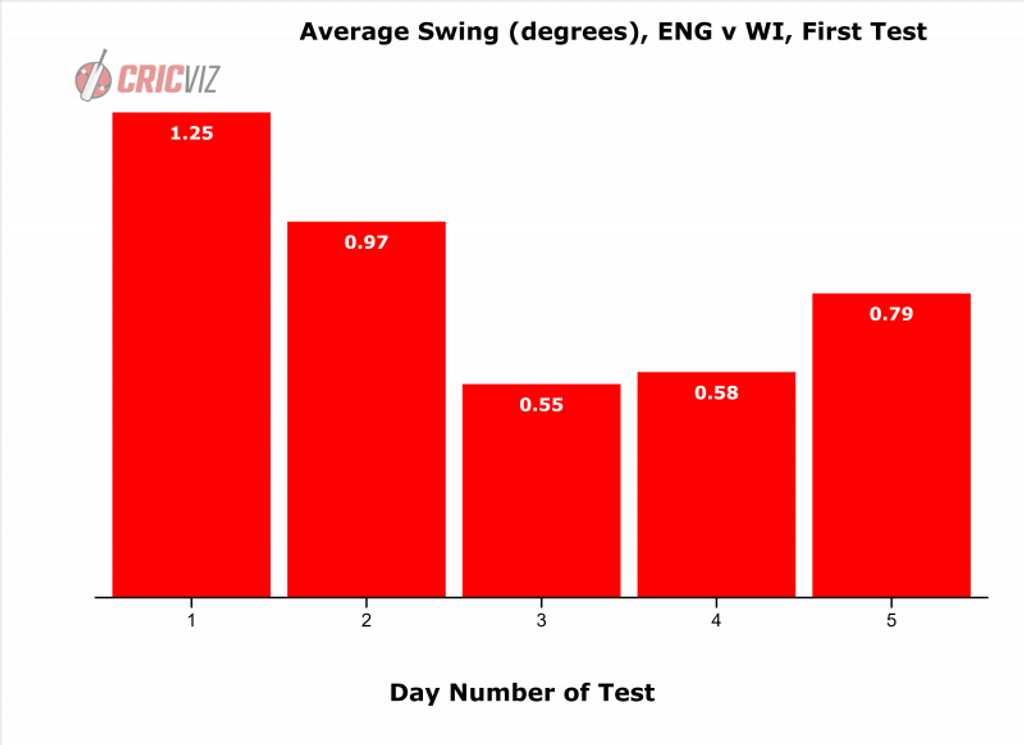

In the 102 English Tests for which CricViz have ball-tracking data, only eight have seen less swing movement than we saw this match. The combined lateral movement across the Test was 1.28° – only four Tests in England since 2006 have seen less. The last time that James Anderson found less swing than in a home Test, than he did this week, was July 2017; the last time he found less seam, was May 2016. When Jimmy isn’t moving it off the straight, conditions – in the broadest sense of the word – invite attention.

The effect of it was pronounced. CricViz’s metric for analysing conditions – PitchViz – suggests that this opening Test in Southampton saw some of the best conditions for batting that we’ve seen in England for the last decade. It’s only thanks to two of the most vulnerable batting orders we’ve seen in Test cricket over the last few years, that we saw a result.

Well, that and the fact that this England team were playing. Since the start of 2017, the beginning of the Joe Root-era, England have played 40 Test matches, and according to PitchViz England haven’t won any of the eight ‘flattest’ matches they have played. By contrast, they have won five of the eight ‘liveliest’ Tests they have played. In this context, “flattest” means “best conditions for batting”. This is hardly groundbreaking stuff; England are good when the ball is doing a lot, but struggle when it isn’t. But in this Test, what aspect of England’s play was particularly to blame?

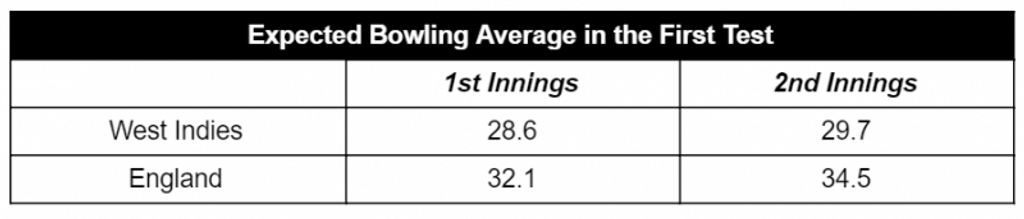

England’s batsmen were partly to blame for the defeat – they underperformed (according to the balls they faced) significantly in the first innings, to the tune of almost 90 runs. According to our Expected Wickets model, the balls the West Indies bowled in the first innings should have averaged 28.6 – England ensured they were rather more effective. Yet in the second innings, Stokes’ batsmen overperformed, albeit marginally, given the deliveries they faced. The control of Dom Sibley and Rory Burns, despite their frustrating dismissals, gave England solidity in a quiet phase of the game. The lower order collapse was a cause for concern, as always, but the overall performance in the innings was promising.

As such, focus should stay on England’s attack. The West Indies bowled better deliveries than England across the Test match, according to that same Expected Wickets model; they bowled better in the first innings, and in the second innings. The weather may have accounted for the first innings disparity, but it could not have for the second.

Were England right to forfeit the right to bowl in those helpful conditions?

Those fourth innings issues, with the pitch not breaking up significantly, were decisive. Ben Stokes alluded to the fact that he thought the game would come down to England’s first innings against the West Indies fourth innings – in essence, England’s batting under clouds v West Indies’ batting on a turning surface. Stokes was well within his rights to expect that this Southampton pitch would spin, given his own recent experiences. In 2018, the last Test played here, Moeen Ali bowled England to victory, finding 5.2 degrees of spin, aided by the footholes created by Sam Curran. Only one other match Stokes has played on home soil has spun more in the final innings of the match, and that leaves an impression.

The absence of a left-armer, and the rain around on the first day, ensured the pitch this week behaved rather differently. But as Stuart Broad pointed out on Twitter, when you toss the coin on Day 1, you don’t know what the clouds are going to do at lunchtime on Day 2. There were so many variables in this match – lack of preparation for players, the changes to the ball-shining regulations, weather – that focusing on the key aspect of the last Test at this venue, makes sense.

What do England do next?

Going to Old Trafford, England are left in a bit of a bind. Far too often in this Test, their attack looked toothless. They had none of their usual swing and seam, and were unable to play in the way they normally do at home.

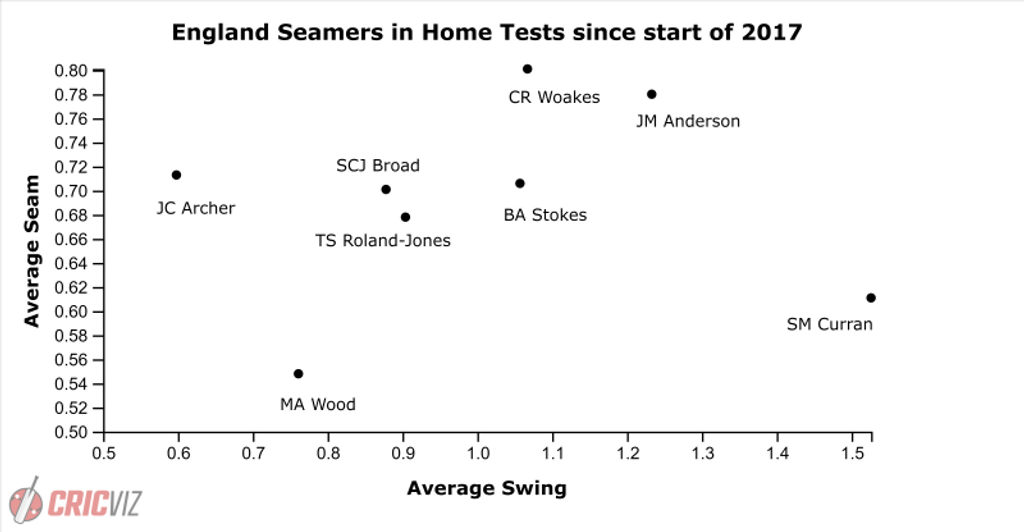

Yet is that because they didn’t pick Stuart Broad or Chris Woakes, men used to finding that movement? Or is it, given the issues James Anderson had finding lateral movement, an issue of the conditions in which this Test took place? In essence – is it worth picking swing bowlers if you can’t use saliva on the ball?

The only man to swing the ball consistently was Jason Holder, under clouds on Day 2. Holder has a track record of swinging the ball more than anyone in the world, but even he couldn’t sustain it when the clouds rolled back. It is too early to suggest that the lack of saliva was the crucial factor, but given concerns from many going into the Test, one can only wonder. Other factors – such as the unusually large number of high pace bowlers on show – could just as easily be the cause.

Old Trafford is, traditionally at least, the quickest pitch in the country. England have already used the fragile Wood in the first match – to play him in another, after such a long lay off, would be asking for trouble. Realistically, England will have to move away from all out pace, and back to a more familiar home-style attack, on a pitch which could well offer more to the likes of Wood.

Regardless, the issue for now, as it has been for a while, is that England still only win when they’re swinging.