On a day that saw the initiative swing back and forth between the two sides, CricViz’s Patrick Noone looks at how West Indies’ rock shaped the innings for the hosts on Day 1 in Barbados.

Patrick Noone is an analyst at CricViz.

Cricket is often guilty of misty-eyed nostalgia, of harking back to bygone eras that may or not have actually existed in reality. No team is subject to such wistful reminiscence more than West Indies. Rarely are the current team able to get through a series without lengthy discussions about former greats and past glories, solemn reflections where we all wonder where it all went wrong.

We are constantly reminded of how far short the modern team are falling in relation to some of the greatest sides ever assembled and, until West Indies hit those heights again, the current side is burdened by their predecessors’ success, haunted by the black and white images of those that have gone before them.

Batting technique is another area that is subject to a similar kind of treatment. It has become fashionable in some quarters to decry the influence of T20 batting and to suggest that batsmen no longer have the defensive technique required to prosper in Test cricket. As though there is a ‘proper’ way to bat and that nobody currently playing the game has the patience or the knowhow to execute a ‘traditional’ Test match innings.

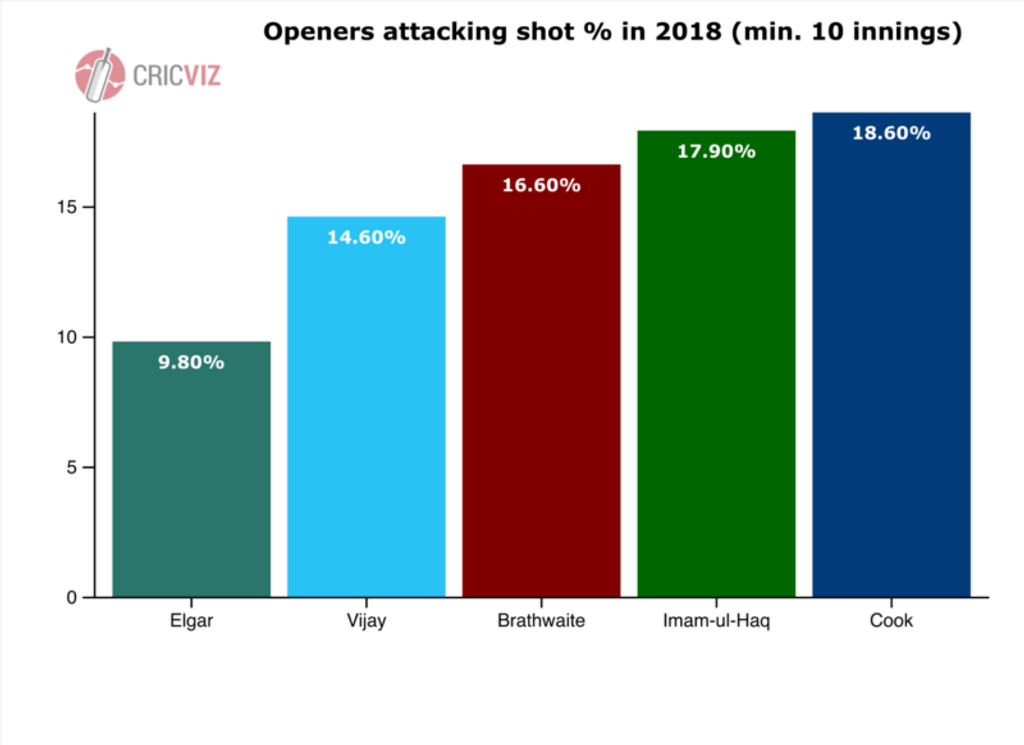

It is therefore ironic that, for all the pearl-clutching about the lack of both talented West Indian players and batsmen capable of slowly accumulating runs in a Test innings, Kraigg Brathwaite has shown himself to be both. The right-handed opener is not one you could ever accuse of flamboyancy; of openers to have batted ten innings or more during 2018, only Murali Vijay and Dean Elgar attacked the ball less frequently than Brathwaite.

Today, Brathwaite took that reticence to attack to new heights. In the first hour, he scored just five runs from the 48 balls he’d faced and had not attacked a single delivery. At the other end, the debutant John Campbell was teeing off, relatively speaking, and had moved to 29 from 42 balls, attacking 19% of the time.

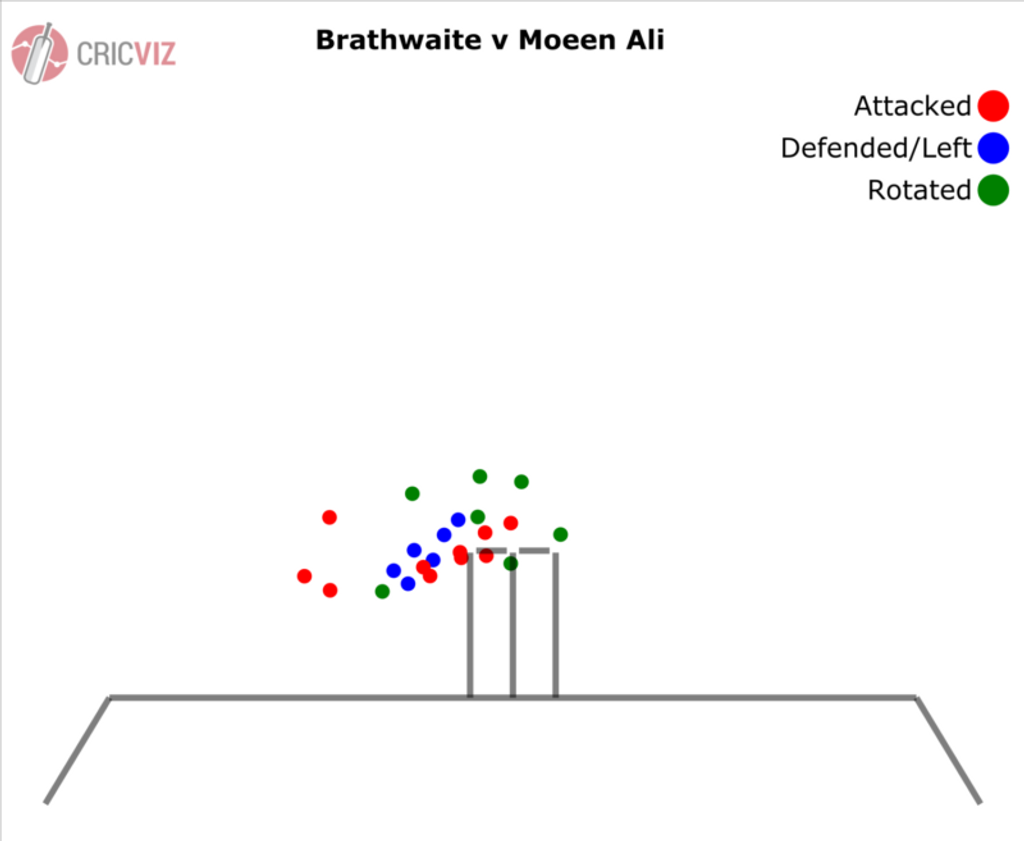

Brathwaite remained resolute though, happy to let Campbell take all the risks, and played his first attacking shot to the first ball he faced from Moeen Ali, the 48th of his innings overall. It was telling that Brathwaite immediately went after England’s spinner; across his career, he attacks the slower bowlers significantly more than the quicks but, perhaps more pertinently, he faces eleven more balls per dismissal when facing seam.

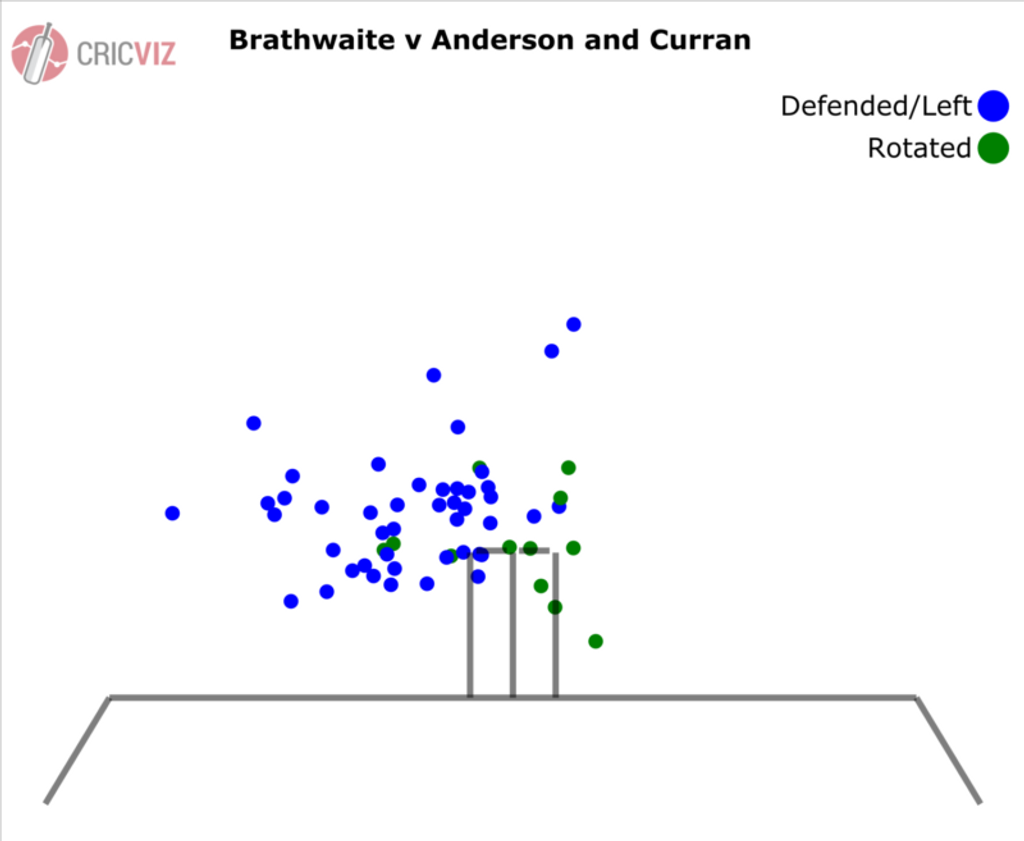

Today, Brathwaite dealt in extremes. By the time he was finally dismissed for 40 from 130 balls, he had still not attacked a single delivery from either of England’s opening bowlers, but had scored 19 runs off the 23 balls he faced from Moeen. When facing 20 balls or more against a spinner, Brathwaite has only twice attacked more than the 43% he did today against the off-spinner.

Everything outside his off-stump from the new ball pair, Brathwaite either defended or let go. Against Moeen, the wider the ball was, the more likely it was to be attacked. Furthermore, Brathwaite was light on feet, stepping out of his crease on three occasions to score two fours and a six as he began to go through the gears.

Brathwaite is not an opener in the mould of someone like David Warner or Virender Sehwag. He will never blast bowling attacks away but he has his method and it largely does the job of seeing off the new ball for the strokemakers down the order. His innings was a throwback to ‘giving the bowlers the first hour’ and laying a platform that allowed Shai Hope, Roston Chase and Shimron Hetmyer to kick on when conditions were more benign and the shine had been taken off the ball.

The half-centuries of Hope and Chase might have been more eye-catching, Hetmyer’s might have been more explosive, but none of those innings would have been possible without Brathwaite’s defiance that went before them. Nevertheless, each of them showed a level of application and skill that suggested that Caribbean cricket is perhaps not as deep in the mire as is often perceived. And, without question, the ability to bat a long period and play out a traditional Test innings is anything but a lost art.