There have been a number of days like today in the last few years. Days when England’s batting has collapsed dramatically and significantly – costing them Test matches in a few madcap hours of flashing willow, forlorn batsmen and furrowed English brows. First there was Centurion in 2016 – all out for 101. Then not long after they were flattened in a session in Dhaka by Bangladesh before repeating the trick against New Zealand in Christchurch in 2018. Last August, in amongst a 4-1 series victory against India, they still contrived to be bowled out in a session – rolled for 136 in Nottingham. England’s batting has been vulnerable to implosion for some time now.

CricViz analyst Freddie Wilde sheds light on the numbers that prove England’s batting is in crisis.

There have been a number of days like today in the last few years. Days when England’s batting has collapsed dramatically and significantly – costing them Test matches in a few madcap hours of flashing willow, forlorn batsmen and furrowed English brows. First there was Centurion in 2016 – all out for 101. Then not long after they were flattened in a session in Dhaka by Bangladesh before repeating the trick against New Zealand in Christchurch in 2018. Last August, in amongst a 4-1 series victory against India, they still contrived to be bowled out in a session – rolled for 136 in Nottingham. England’s batting has been vulnerable to implosion for some time now.

The scale of these disasters have made it very easy to get hysterical about England’s batting in recent years. With every new collapse has come another phase of furious debate, of pundits, commentators and columnists bemoaning the county system, the corrosive influence of white-ball cricket on red-ball techniques and questioning the mental strength of England’s players to dig in and bat for prolonged periods of time.

“Australia will begin tomorrow leading by 283, the dogged Marnus Labuschagne still at the crease, and still doing his best Steve Smith impression.”@Ben_Wisden reports on an incredible day at Headingley. https://t.co/8JIxGMNmMt

— Wisden (@WisdenCricket) August 23, 2019

However, such hysteria has often missed the broader truth that we are currently in an era in which the ball has comprehensively dominated the bat in Test cricket all around the world. Through a combination of superb bowlers – particularly fast bowlers – operating in conditions that have provided them with considerable assistance, batting in Test cricket has not been this difficult for some time.

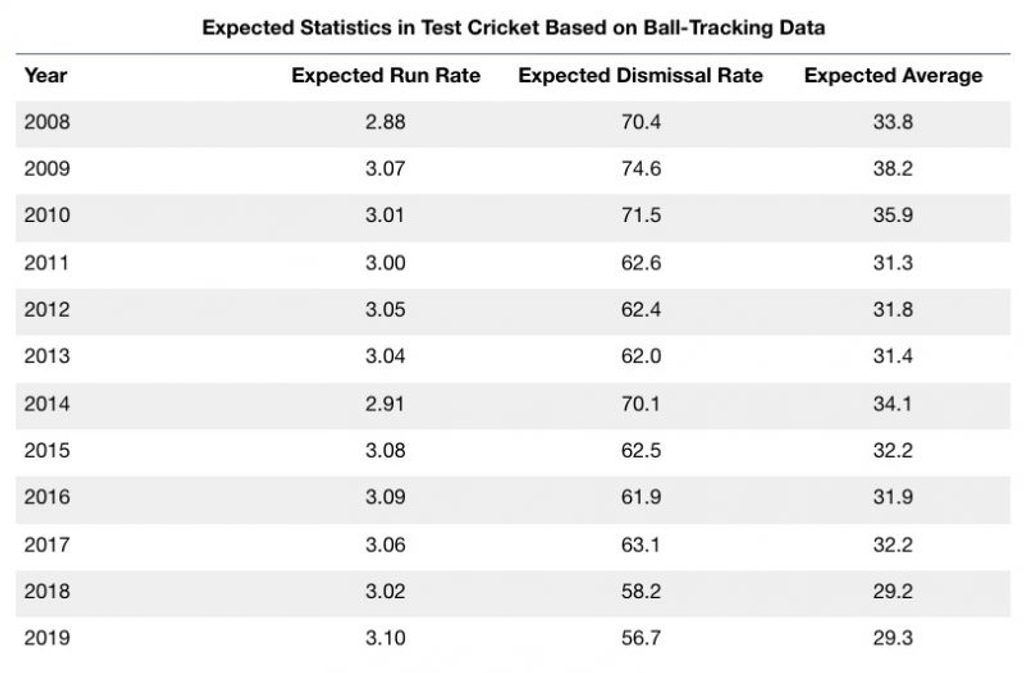

Thanks to ball-tracking data it is possible for us to quantify the difficulty of batting using CricViz’s unique Expected Runs and Wickets model. The model works by taking all of the ball-tracking components that make that delivery what it was – from release angle all the way through to the bounce and deviation of the ball – and comparing how batsmen have fared against deliveries with similar components.

What this model shows is that in the last four years, but particularly in the last two years, the Expected Batting Averages of batsmen based purely on the deliveries that they have faced, has plummeted, the primary reason for this has been a significant drop in the Expected Dismissal Rate. That is to say, averages are falling not because runs are harder to come by, but because it has become significantly harder to survive at the crease.

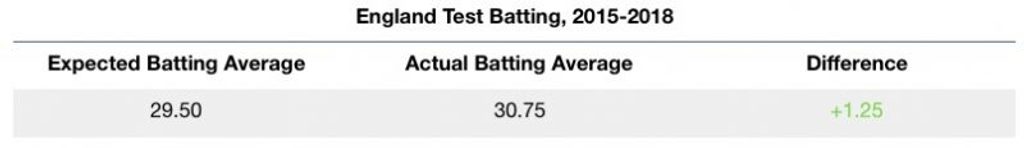

With consideration for the difficulty of modern Test batting, England’s struggles in recent years are put into perspective. Sure, they have struggled, but so have most Test batsmen in this period. Analysing Expected Statistics by team further underlines this point. Between May 2015 – when Trevor Bayliss was appointed as England coach – and the end of 2018, England’s batsmen in fact marginally over-performed relative to an average Test team based on the balls they had faced by +1.25 runs.

Admittedly, marginally over-performing relative to an average Test team is not perhaps what a team as well-funded and well-resourced as England should be aspiring to, but it does at least give some context to their struggles. Of course, the collapses and implosions between 2015 and 2018 were dramatic and concerning – and hinted at significant problems within England’s batting line-up, but they were far enough apart and separated by enough substantial scores to keep England’s head just above the water-line.

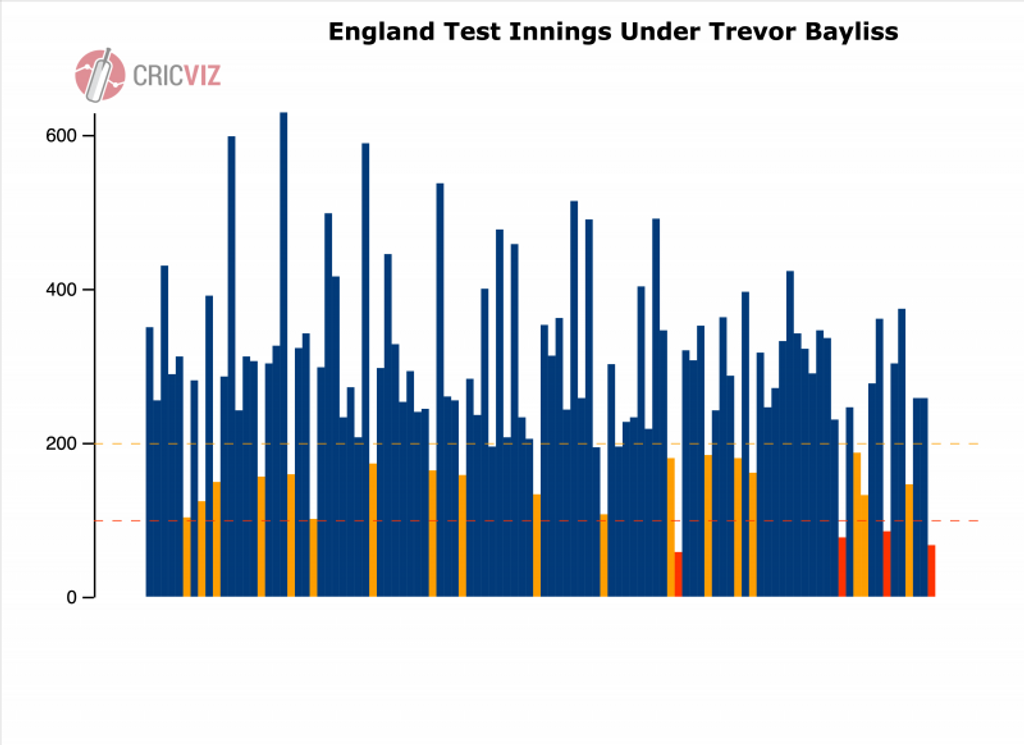

However, this year things have been different. The time between collapses has become smaller – two innings between the 77 all out in Barbados and the 132 in Antigua, and then just two more before the 85 all out against Ireland and now only five more before the 67 all out against Australia. Additionally, not only have the famines come around more often but the feasts are disappearing as well. The graph below shows all of England’s Test innings under Bayliss and where previously England’s batsmen would at least be able to intersperse the smaller scores with some relatively substantial ones, that quality now appears to be dwindling too.

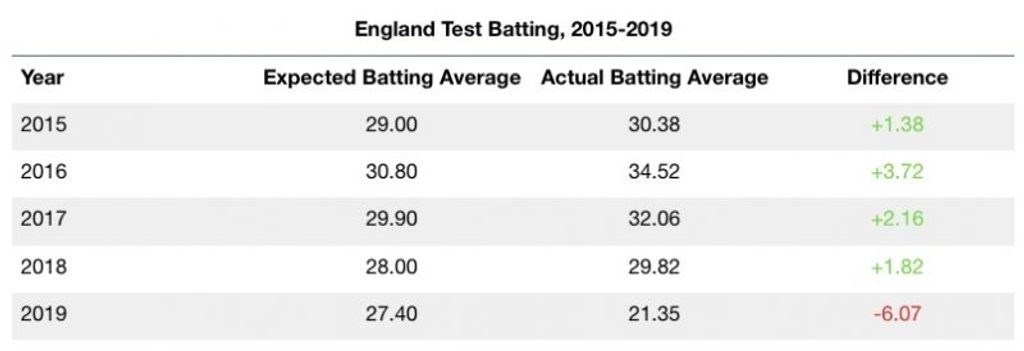

In 2019 England’s overall average of 21.35 runs per wicket is – shockingly – their lowest in a calendar year since 1922 and their lowest in a year when they have played at least three Test matches since 1909. And while these figures clearly illustrate the scale of England’s batting crisis, given the difficulty of batting in the modern era what perhaps provides a more analytical perspective on their problem is that they are now underperforming relative to expectations by a massive -6.07 runs per wicket.

Hysteria has often greeted England’s batting performances in recent years—perhaps unfairly given the current climate of ball dominating bat—but now in 2019 it appears that the time for serious and severe introspection has arrived. You’ve been told it for years but now it is finally true and indisputable: England’s batting is in crisis.