CricViz analyst Patrick Noone analyses the opening day at Bay Oval.

“When you win the toss – bat. If you are in doubt, think about it, then bat. If you have very big doubts, consult a colleague – then bat.”

The above quote, attributed to WG Grace, is reflective of a bygone era. An era of sticky wickets and gentlemen and players when runs on the board were king. The game is wildly different today and perceptions have changed since Grace made his famously dogmatic proclamation. The rise of short-form cricket has encouraged teams to regularly chase while teams make informed decisions at the toss based on a multitude of data rather than convention.

However, despite the many advances that the game has undergone in the last 150 or so years, there remains an ingrained culture in the cricketing psyche that batting first is somehow the ‘correct’ choice to make when the coin falls in your favour. Nasser Hussain’s decision to bowl first in Brisbane in 2002 has passed into infamy, but you hear less about Joe Root opting to bat first at Lord’s against Pakistan in 2018, despite both matches ending in similarly heavy defeats.

An excellent day for England.

They end it on 241-4 with Stokes finishing on 67*.#NZvsENG pic.twitter.com/z4bLPjs70B

— Wisden (@WisdenCricket) November 21, 2019

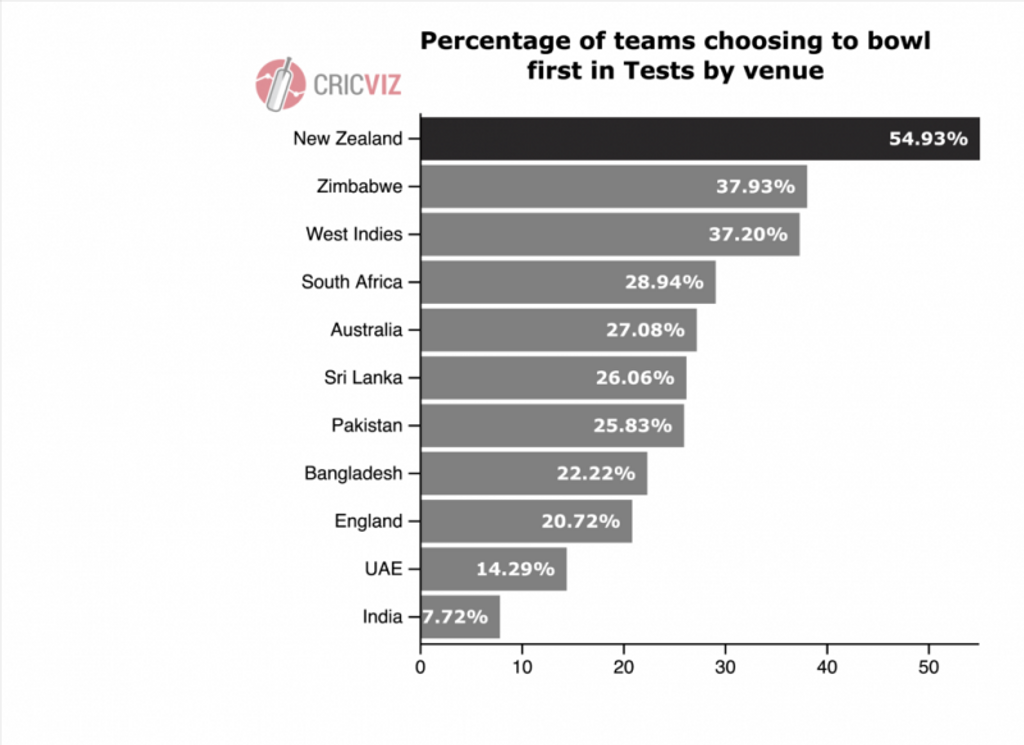

In Test history, 73 per cent of teams winning the toss have chosen to bat first. Even in more recent, enlightened times, that figure is still up at 67 per cent in the last 20 years. Yet New Zealand has always been a setting in which that trend has been bucked. Nearly 55 per cent of the 213 matches hosted there have seen the team winning the toss choose to bowl first; no other country has seen more than 37 per cent of teams choose to insert the opposition.

The recent trend has been even more skewed in favour of teams opting to bowl, with only two of the previous 33 toss winners before today choosing to bat first in New Zealand. Perhaps seduced by pitches that often contain more than a tinge of green, or the reputation New Zealand has of being swing-friendly, teams have overwhelmingly opted to get ball in hand on the first morning.

Except today, at a new Test venue, England chose to go against the grain. Despite the typically verdurous appearance of the pitch Root opted to bat, making him the first captain for two and a half years to choose to bat first in New Zealand.

Making such a decision against Tim Southee and Trent Boult in home conditions might have provoked trepidation for a touring team, especially one with as many recent batting demons as England, yet the new opening partnership of Dom Sibley and Rory Burns acquitted themselves well while New Zealand could be accused of wasting the new ball.

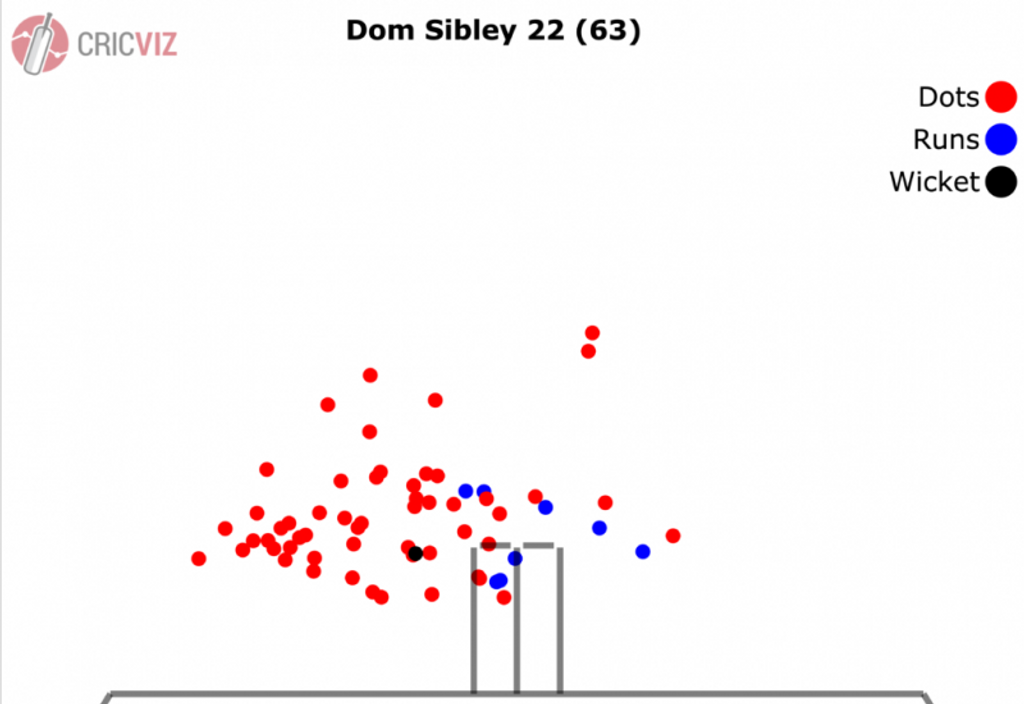

On Test debut, Sibley faced 63 balls and was able to see off the threat of Southee and Boult, despite the new ball pair finding a healthy average of 2.2° of swing and 0.4° of seam movement. Sibley was relatively untroubled by the movement and even less so by the line of attack that New Zealand adopted.

In first-class cricket, Sibley scores 64 per cent of his runs on the leg-side. New Zealand either didn’t know this, or executed their plan to counter it poorly, bowling too straight when they went straight and too wide when they went wide. It meant Sibley could flick off his pads at will or simply let the ball go. It was not until Colin de Grandhomme found the line that was close enough to Sibley’s stumps that he couldn’t leave it, and full enough that he felt he could score runs off it.

Sibley’s debut innings wasn’t as long as he would have wanted it to be, and he’s unlikely to win many awards for aesthetics, but it was effective in seeing off the new ball threat and vindicating the decision to bat first. A compelling argument could be made that New Zealand’s wayward lines were as much a product of Sibley forcing the bowlers to bowl where he wanted them to as it was the Kiwi bowlers searching for the magic delivery.

That patience and diligent shot selection is something England have lacked in recent years. Since the start of the 2018 home summer, only three innings of 50 balls or more from England openers have seen a higher leave percentage than Sibley’s 37 per cent today. It’s a statistic that is indicative of both England’s new regime and the one that preceded it; new coach Chris Silverwood has emphasised the need for batsmen to ‘bat time’ and become a more solid Test match outfit. The experiment to turn Jason Roy into a swashbuckling Test match opener already feels like a distant memory.

50 for Joe Denly!

It's his fourth in his last four Tests for England. #NZvENG pic.twitter.com/T46ALZd25Z

— Wisden (@WisdenCricket) November 21, 2019

These were the first tentative steps into England’s Cautious New World on what was far from a perfect day for the visitors. Root’s strange run of form continued as he nicked off for just two off 21 balls, while Joe Denly had his cage rattled by Neil Wagner as England failed to significantly up the run rate in the middle session. In their defence, so rarely have England’s openers laid a platform for the middle order, it should hardly be a surprise when they’re unable to capitalise on one when it arrives.

But with the emphasis now seemingly less on scoring rates and more on crease occupation, England will be pleased with the efforts of all of the top three batsmen. Between them, Sibley, Burns and Denly faced 63.3 overs; only once since the Boxing Day Ashes Test in 2017 have an England top three faced more balls in an innings.

Last time they arrived on New Zealand soil, England were blown away for 58 in Auckland – on that occasion they effectively chose not to bat, even after being sent in by New Zealand. Today, they might have had doubts, but they chose to bat; they might have big doubts, but they chose to bat. The transition from one era to the next might not be seamless, but this was a step in the right direction for an England side looking to embrace its new identity.