Ben Jones analyses the ever-increasing role of the slower ball in England’s ODI bowling plans.

Slow isn’t a word you often see applied to this England ODI side.

Rapid? Sure. Reckless? Often. But slow? Rarely is anything to do with this collection of dashers and chargers labelled as being slow.

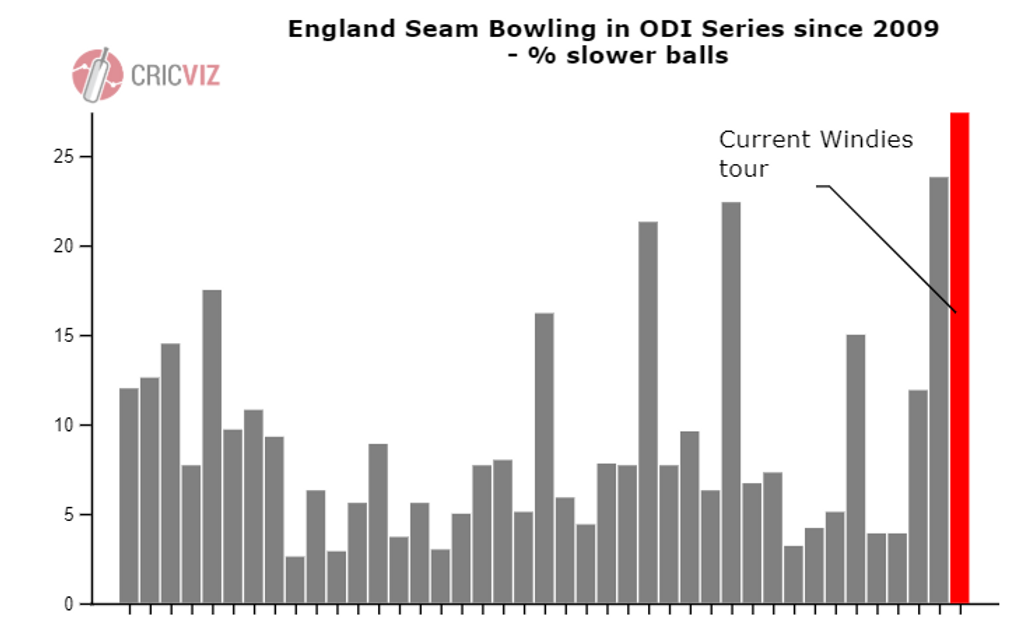

Yet in one crucial instance, Eoin Morgan’s boys are attracting this label. In the ODI series taking place in the Caribbean, England’s seam attack have bowled more slower ball variations than they have done since 2009. That’s right. The last time England were reaching for this tactic as often as they are now, Sam Curran was 11 years old, David Cameron was yet to be elected Prime Minister, and Jonathan Trott hadn’t debuted in Tests.

It feels like a sensible move, in the context of this series. On pitches in the West Indies that have welcomed batsmen with open arms, giving bowlers a cold shrug of the shoulders, any innovation is necessary for the men with the balls in hand. Going through the variations makes sense.

But the slower ball is still a bold choice. It doesn’t matter what the format is, you will still be swamped by ex-pros telling you that yorkers are the only acceptable ball to bowl in white ball cricket. “Whatever happened to the yorker?” they cry, as another attempted 91mph yorker that missed by 6cm is thwacked over the rope with a nonchalant flick of the wrist from a batsman trained to perform precisely that move. In opposition, the slower ball is the subtle variation. If it goes wrong, it looks like you have tried to be too clever, the greatest sin one can commit in any sport, in any field of life. Cricket’s had enough of experts.

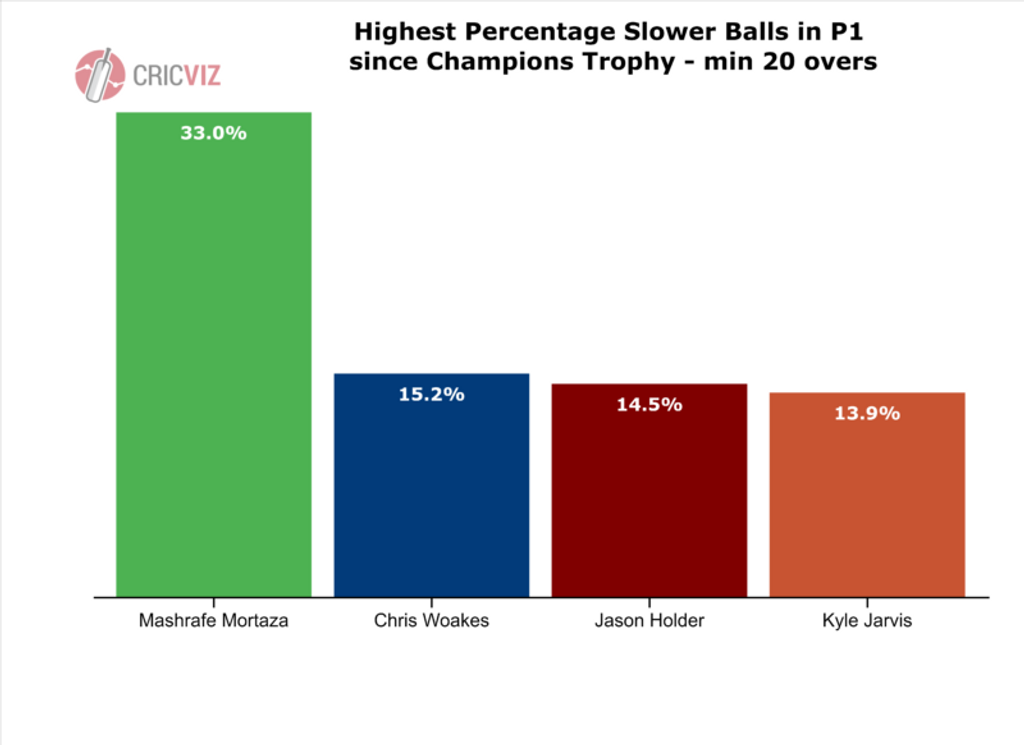

Over the last few England series, the tactic has been lead by Chris Woakes, the leader of the attack in general. On the face of it, Woakes appears to be the sort of one-dimensional English seamer that defined the pre-2015 team, but he is a far cannier operator than his red-ball reliability suggests. Since the Champions Trophy, he bowls more slower balls at the start of ODI innings’ than almost anyone else in the world.

That willingness to move away from traditional upright seam bowling is surprising for a bowler like Woakes, but his is the approach that looks increasingly to be influencing England’s white ball bowling. It is innovation from the top down that appears to be setting the tone.

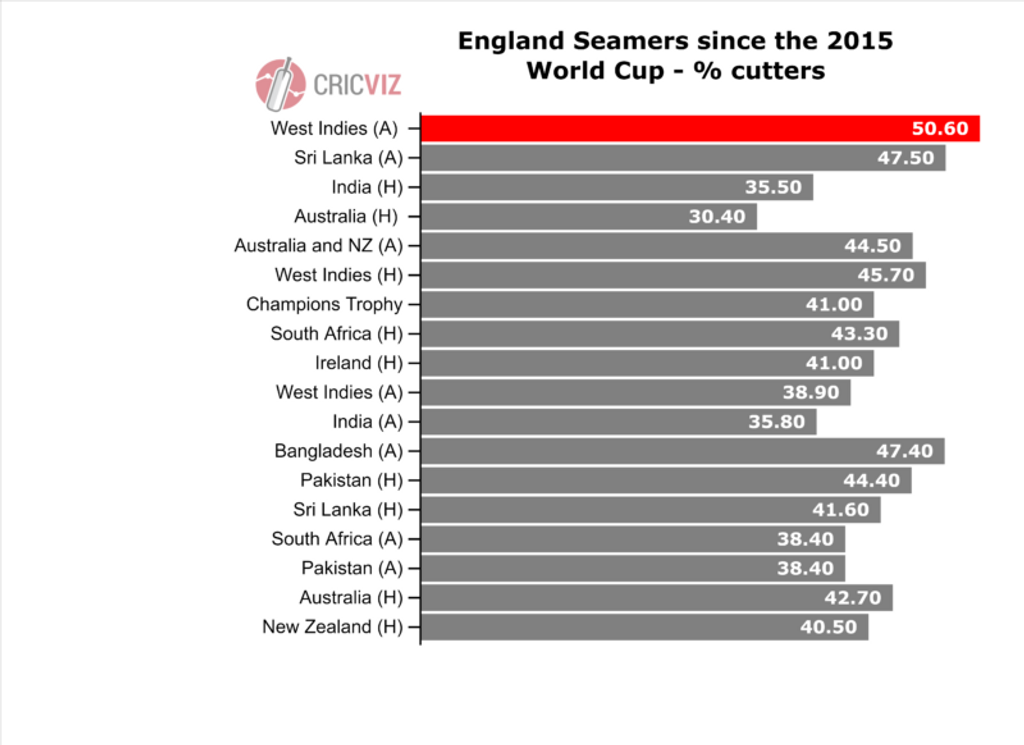

The modern white ball bowler has more variations than any generation, more aware of the tricks and nuanced specifics of what’s being delivered than those who came before. T20 dictates that this is the case. What England seem to have been focused on bowling more than any other, however, is the cutter. 51 per cent of their deliveries this series have deviated significantly either right or left, the most for any ODI series since the last World Cup.

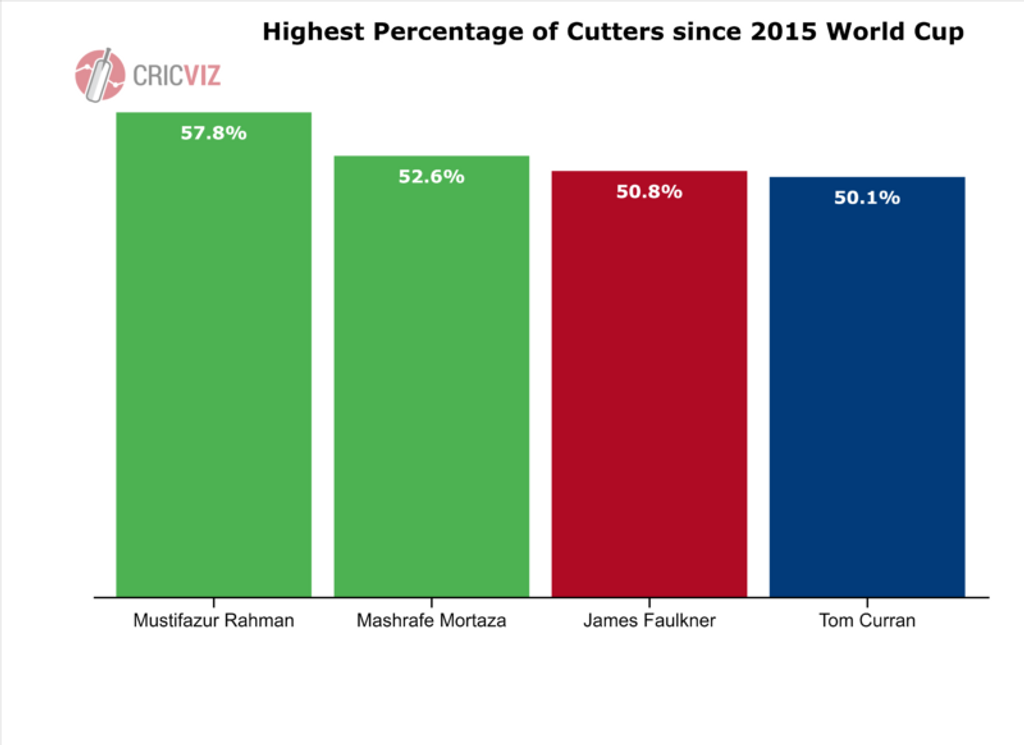

This trend has undoubtedly been lead by Tom Curran, the Surrey man who has bowled more cutters than almost any other bowler since the 2015 World Cup. Renowned as master of the variation, he dominated the BBL this winter and dragged a mediocre Sydney Sixers squad to the semi-finals. They subsequently went out of the competition when he left Australia for the England camp; few in the world are as good at what Tom Curran does, as Tom Curran.

He is of course only a fringe player in the international set-up, but he represents an interesting trailblazer for the more established players. On the pitches that we’ll see in the World Cup this summer (flat, true surfaces for the majority of the competition in all likelihood), whether bowling sides are able to adapt amidst the mayhem, keep trying alternative tactics, and eventually restrict sides to 325 rather than 350, could be just as important as the ability to bowl sides out for 220. Slower ball bowling, in all its guises, is a massive part of that.

What’s more, England have plenty of these worldly, modern cricketers. If England do select Jofra Archer in their World Cup side, then they will have considerable T20 experience in their line-up. Curran, Liam Plunkett and Archer himself were all in Australia for the BBL this winter, with varying degrees of success, and the opportunity for them to transfer the nous they have learned in the 20 over format into the 50 over game is an intriguing one. They bring so much to a team.

Ultimately, this England side attract a lot of rather peculiar criticisms. People cling to the idea that they ‘wilt under pressure’, or ‘are prone to a collapse’, but that is almost pathetically clinging to the negative. This is the best white ball team England have ever produced. They are the best in the world. Every side is prone to collapses and struggling occasionally, but for England those struggles interrupt strings of flawless defeats, unchecked brilliance, rather than the inconsistency that passes as qualified success for most other teams. The snarky desire from some to measure their performance against perfection, and perfection only, is sad.

However – their bowling is more vulnerable than is ideal, and in the absence of clear personnel improvements, embracing this sort of tactical innovation is the next best option. England have earned the right to be trusted in the last four years, and this seems to be the tactic they are moving towards. If it works, they are dangerously close to becoming the perfect white ball team. Snark all you want – they are slowly treading a path to greatness.