CricViz’s Ben Jones analyses the form of Cameron Bancroft, who is yet to pass 15 so far this Ashes series.

Cameron Bancroft doesn’t look great. That’s generally the case, and it’s been true this summer, but it was particularly true today. Under cloudy skies and floodlights on a grisly morning at Lord’s, batting was never going to be easy. At times, Bancroft made it look impossible.

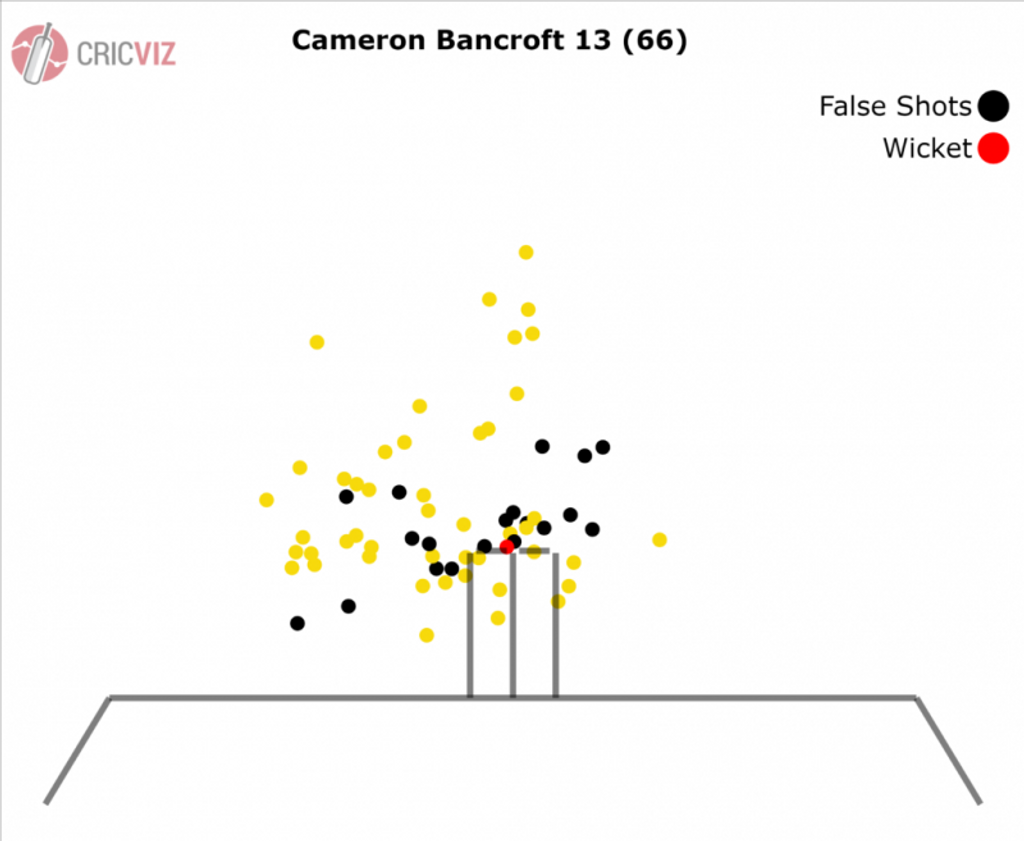

30.3% of his shots brought an edge or a miss – almost twice every six balls. The last time an Australia batted for as long with that little control was November 2016. Part of his charm as a player is that Bancroft’s technique dictates that when he misses the ball, he often gets hit, preferring to wear some deliveries than risk nicking off. Bravery shouldn’t mask the fact that ideally you don’t miss the ball in the first place.

It was hard to watch that period and think, sincerely, that this was an opener of genuine Test quality. The Test openers that Australia could have picked alongside David Warner were Marcus Harris, Joe Burns, or Bancroft himself. Could the other two candidates have done better?

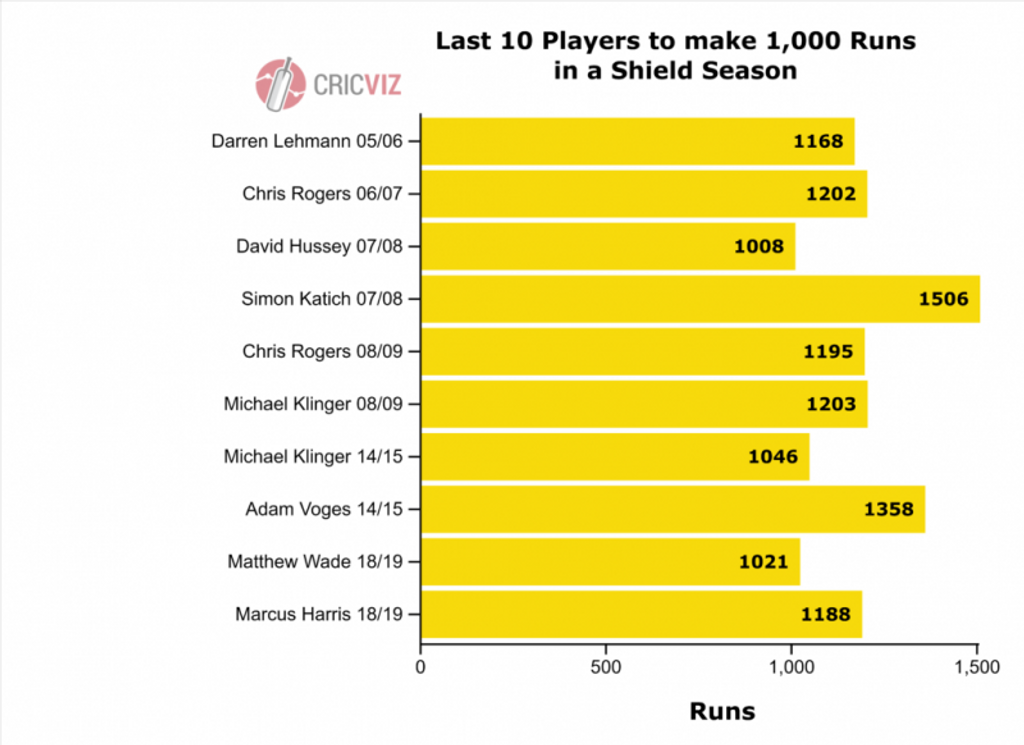

Harris’ case is made on the weight of runs he’s made in Shield cricket. In the last decade, only five players have passed the 1,000 run mark in a season, Harris and Wade both doing so this season just gone. Off the back of that form, Harris was blooded in the home series against India, the world No.1 team, and a side who smelt blood, knowing that history was there for the making.

Spending a summer getting peppered by Jasprit Bumrah and Mohammed Shami is a tough introduction to Test cricket, but Harris passed the test. No Australian averaged more in that series, no Australian scored more runs. Yet two middling Tests against Sri Lanka later, and he was dropped.

Burns has made runs in domestic cricket, runs aplenty, but the bulk of his worth has been proved in Test cricket. Four centuries in 28 innings (one every seven knocks, the same as Ricky Ponting and better than Michael Clarke and Michael Hussey) is testament to his quality at this level. He arrived in England this summer, made a century at Arundel in the warm-up match then was not-out in the second innings, and was then sent home, unselected.

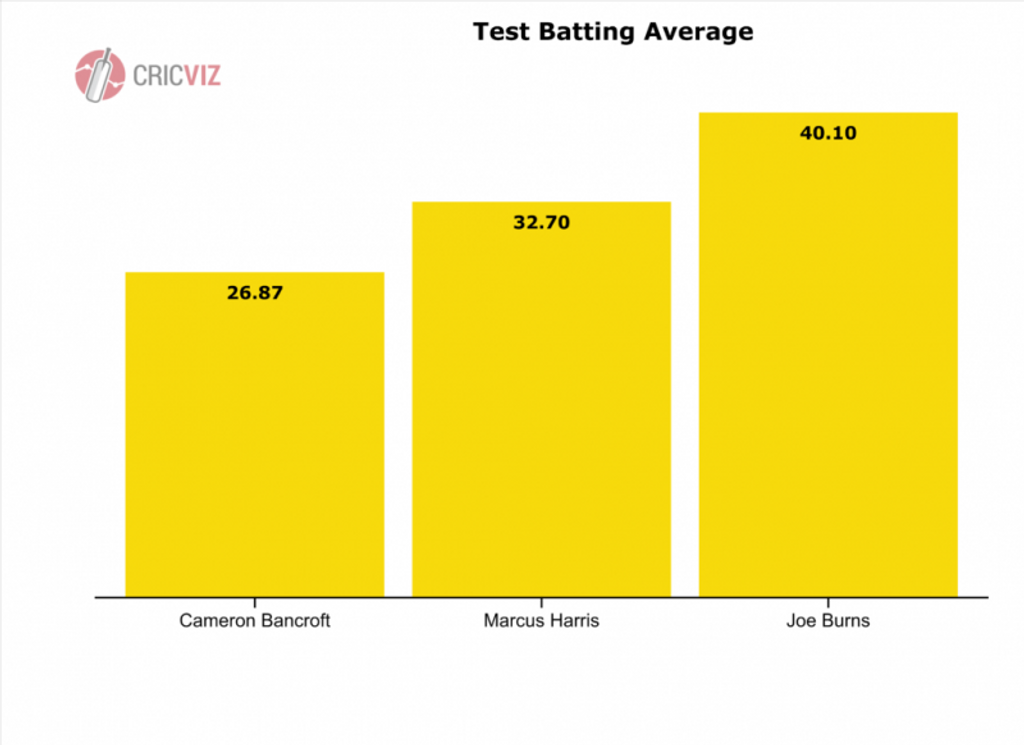

Using that most blunt of analytical tools, the batting average, we can see that Burns has offered substantially more than Harris, who has offered substantially more than Bancroft. In raw returns, Bancroft’s performance is alarmingly poor.

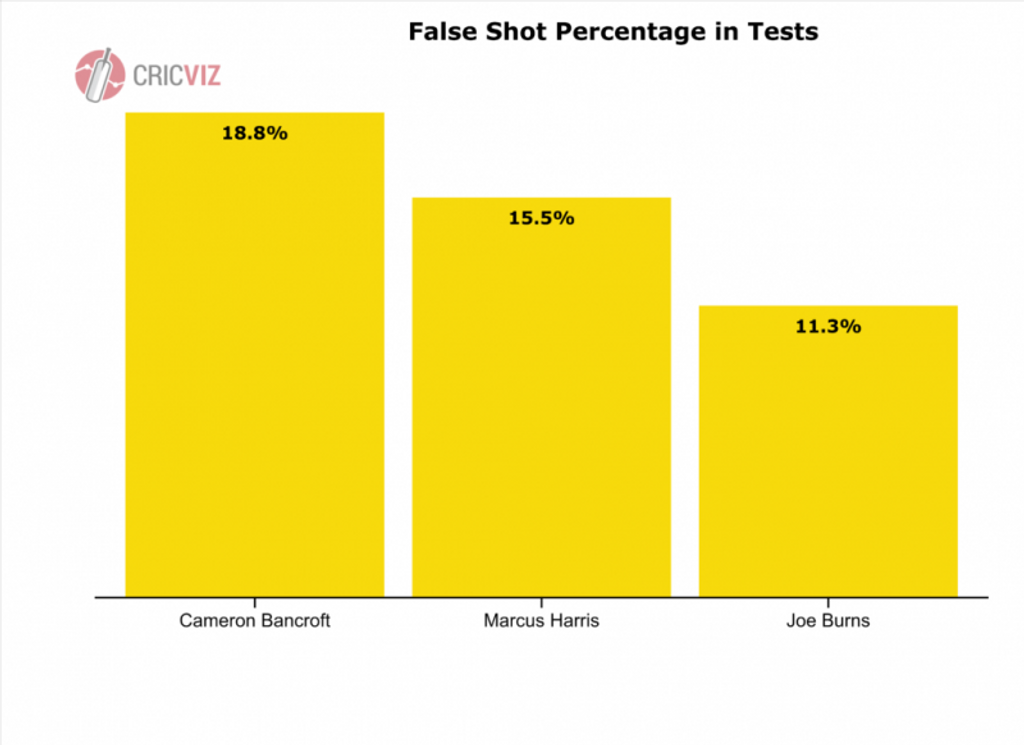

It’s relevant how those runs are made, of course – but in terms of risk and control, Burns is again far and away the outstanding candidate. Just 11% of the deliveries bowled to him have brought an edge or a miss, well below the Test average of 14%, and comfortably below either Marcus Harris or Cameron Bancroft. You would imagine that this has a predictive quality for how a player will go in the long run.

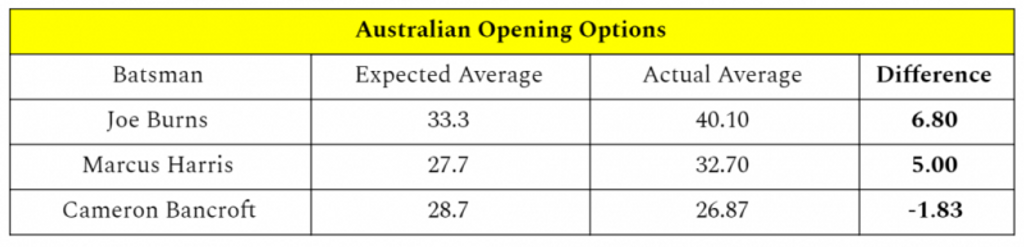

The accusation often thrown at Burns is that he’s made easy runs – we can interrogate this. Our Expected Wickets model uses historical ball-tracking data to calculate what we’d expect the average batsman to score against any given set of deliveries. As you can see, the bowling Burns has faced has an Expected Average of 33.3, the “easiest” of the three opening candidates, whilst Bancroft has faced the “toughest” deliveries.

However, Burns still outperformed what we’d expect. Burns’ average is almost seven runs-per-dismissal higher than we’d expect given the quality of the bowling he’s faced. Harris, even amidst that Bumrah bombardment, is not much further behind. Bancroft on the other hand actually averages less than you’d expect the average batsman to do against the balls he’s faced. He is under-performing.

Of course, Bancroft’s defining contribution in this Test has not been with the bat, but in the field. His catch to dismiss Rory Burns on Day 2 was an outstanding piece of work, and is indicative of his general quality as a fielder. Since the start of 2018, his fielding has saved Australia 20 runs-per-match, illustrating that his value to the team does extend beyond his contribution with the bat. By contrast, Harris’ fielding saves nine runs-per-match, and Burns just five. This deserves to be taken into consideration.

Yet it’s not easy to see, from a pure batting-focused perspective, why Bancroft is in this team. Perhaps it’s a selection based on character, Cameron Bancroft embodying a certain kind of Western Australian grit that Langer wants to thread throughout this XI. By all accounts, Burns does not necessarily have those qualities, and neither does Harris. Those qualities can have value, without a doubt, but the cost is a cricketing one.

Australia will probably draw this match as a result of the rain, but they have a strong chance of taking this series; that may see Bancroft’s place unthreatened, carried along on a wave of success like George Bailey in 2013/14. Should Australia start to struggle in this series, if Smith’s form drops off and others are unable to fill the space behind him, then Bancroft’s character will suddenly start to seem rather less valuable; runs will become currency, and all signs point to the idea that Burns, or to a lesser degree Harris, would score more runs than the incumbent opener.