It was another excellent day for West Indies as England were bowled out for 187 in Antigua. Patrick Noone looks at how the North Sound pitch contributed to a compelling day of Test cricket.

Patrick Noone is an analyst at CricViz.

Cricket pitches are something on which almost everyone has an opinion but almost no-one is an expert. No Test match passes by without lengthy discussions around the surface before, during and after the match.

What should they do at the toss? Will it suit spinners or seamers? Is it likely to break up?

These are all questions asked by fans and pundits alike yet, as England proved in the first Test of this series, it’s possible to be a team full of experienced professional cricketers from past and present and still read the pitch incorrectly.

Every so often though, a pitch comes along that everyone agrees on. In Antigua, England abandoned the two spinner policy from Bridgetown and brought back Stuart Broad, West Indies captain Jason Holder had no hesitation in choosing to bowl first and Joe Root said he would have done the same.

There appeared to be a thick layer of green grass on the strip at the Sir Vivian Richards Stadium and the consensus was that this would be a seamer’s paradise. For the first session at least, it did not disappoint.

West Indies’ seamers found an average of 0.78° of seam movement, the second highest figure they’ve ever extracted from the surface at the Sir Vivian Richards Stadium, behind the 0.92° they found against Bangladesh last year. England made a somewhat bigger score than the 43 that Shakib Al-Hasan’s side put on in July, but it was a measure of how tricky conditions can be at this venue.

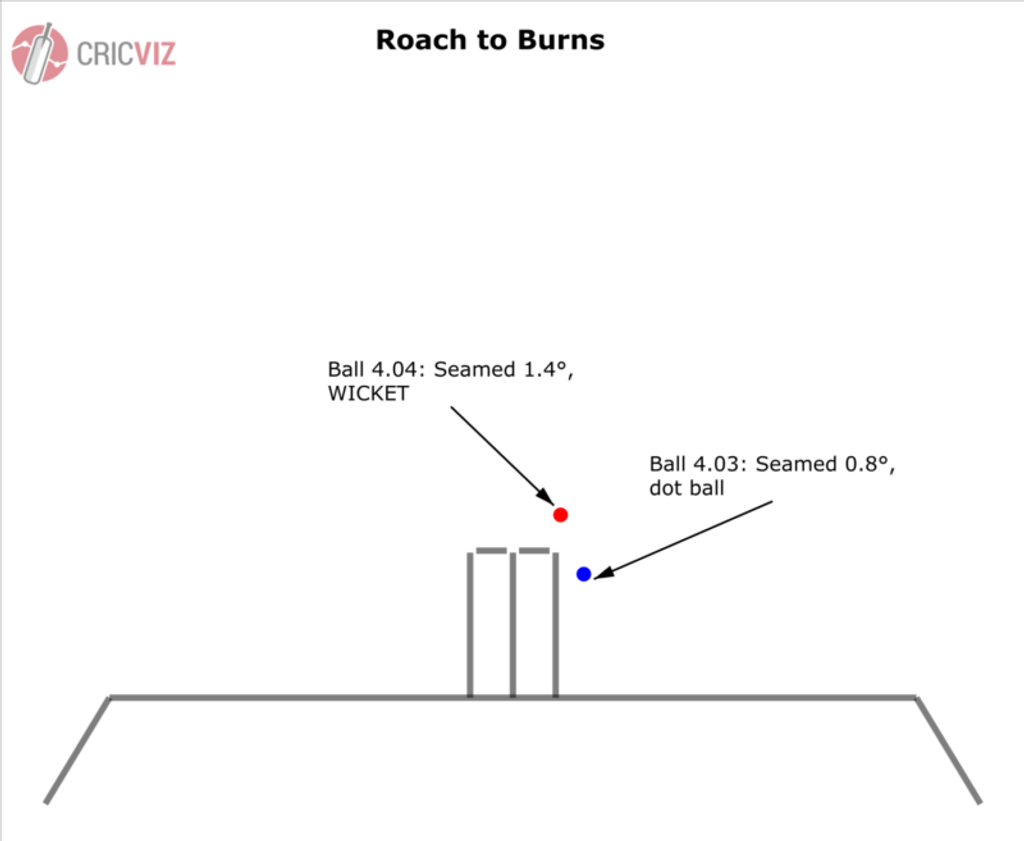

Rory Burns was the first England batsman to depart as Kemar Roach, the tormentor-in-chief from the first innings in Barbados, found just enough movement to find the outside edge of the left-hander’s bat. The previous ball, Burns was able to line up and defend with little discomfort; when Roach was a fraction shorter and found just 0.6° more deviation off the pitch, the England opener felt he had to play and was caught in the slips.

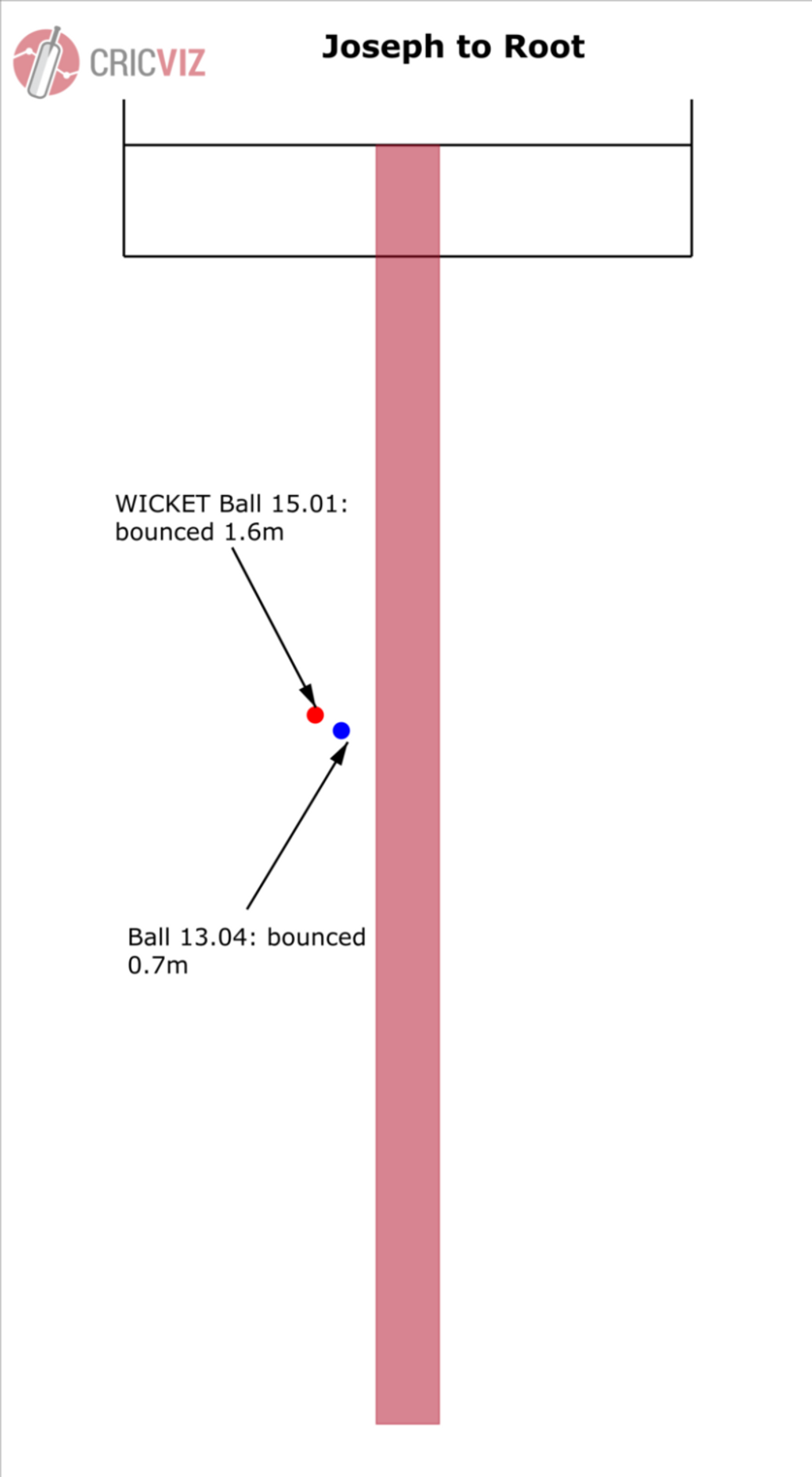

Lateral movement was one thing, variable bounce was quite another and it was balls rising off a length that England found most perilous to play. None more so than Joe Root, who fell to arguably the ball of the day from Alzarri Joseph.

A ball pitching 6.2m from the batsman’s stumps is comfortably in the ‘good length’ region, in fact it’s getting towards being a full delivery. Root went to play it in kind only for it to rear up sharply, deflect off the glove of the England captain and be caught by Shai Hope in the slips after John Campbell had fumbled.

There was not a long wrong with how Root played the delivery – the previous one he’d faced from Joseph had been 18cm fuller but had bounced just 0.7m, compared to the fearsome 1.6m that the wicket-ball reached.

Root’s dismissal, as well as other balls that behaved similarly, prompted the occasional comment on social media that the unpredictability of the pitch made it unfit for Test cricket. But it is that unpredictability that can make cricket such a thrilling spectacle in conditions such as those in Antigua. The feeling that anything can happen with each delivery draws the spectator in; it keeps you glued to proceedings when the behaviour of each ball is a mystery to batsman and viewer alike.

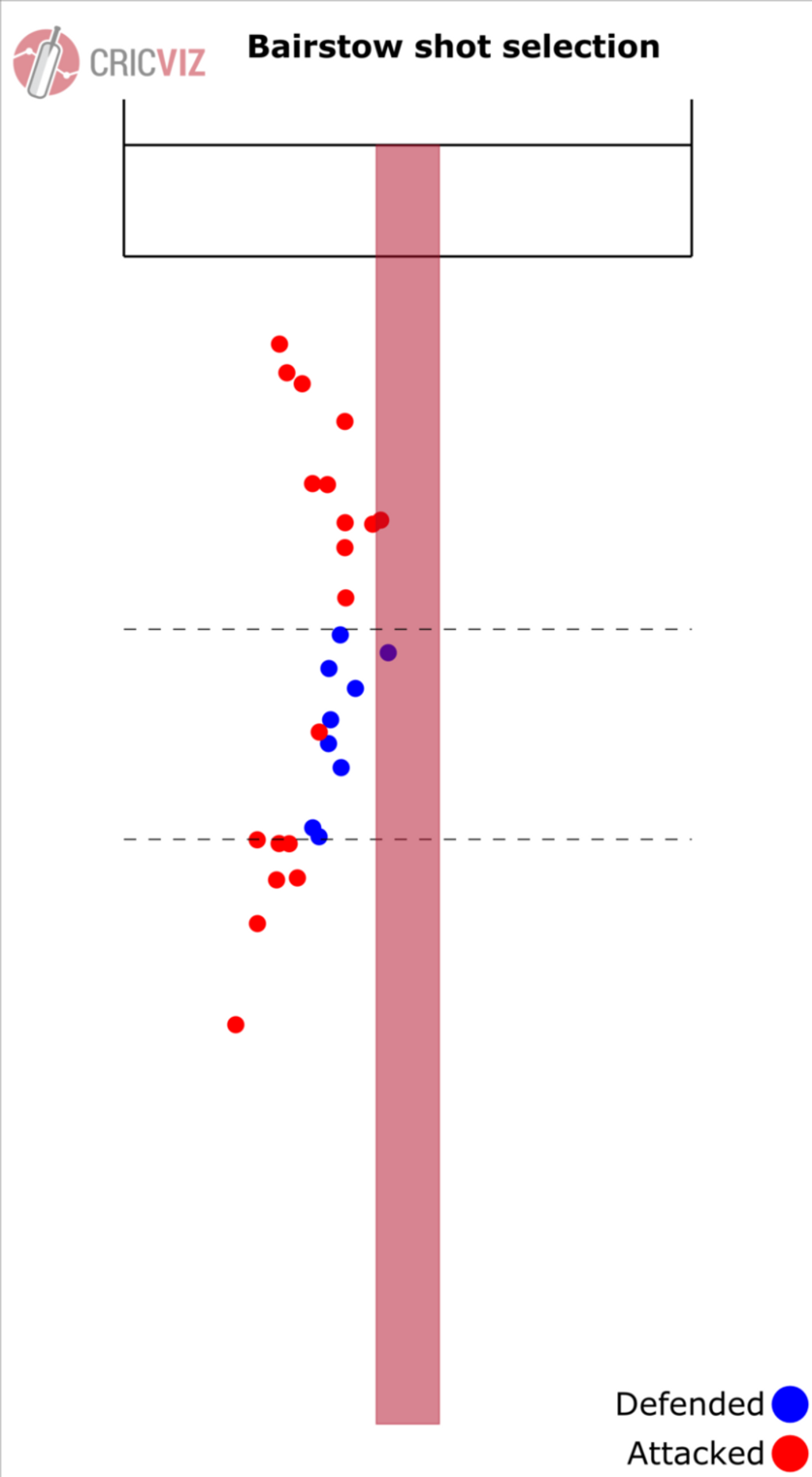

Jonny Bairstow’s approach to counter the demons in the pitch was to play his shots and attempt to force the issue. England’s number three played with the attitude of ‘if there’s a ball with my name on it, I might as well make as many runs as possible before it comes’, and it worked as he raced to a 59-ball half-century.

On a pitch as difficult as this, Bairstow’s was a quite remarkable innings. It was not just a case of taking the necessary risk to counter-attack but to have the ability to execute those shots as well. To put into context how effective Bairstow’s strategy was, his 20 attacking shots yielded 41 runs; that’s a run rate of 12.30 runs per over. Bairstow has never recorded a higher attacking shot run rate in an innings where he’s played 15 or more attacking shots.

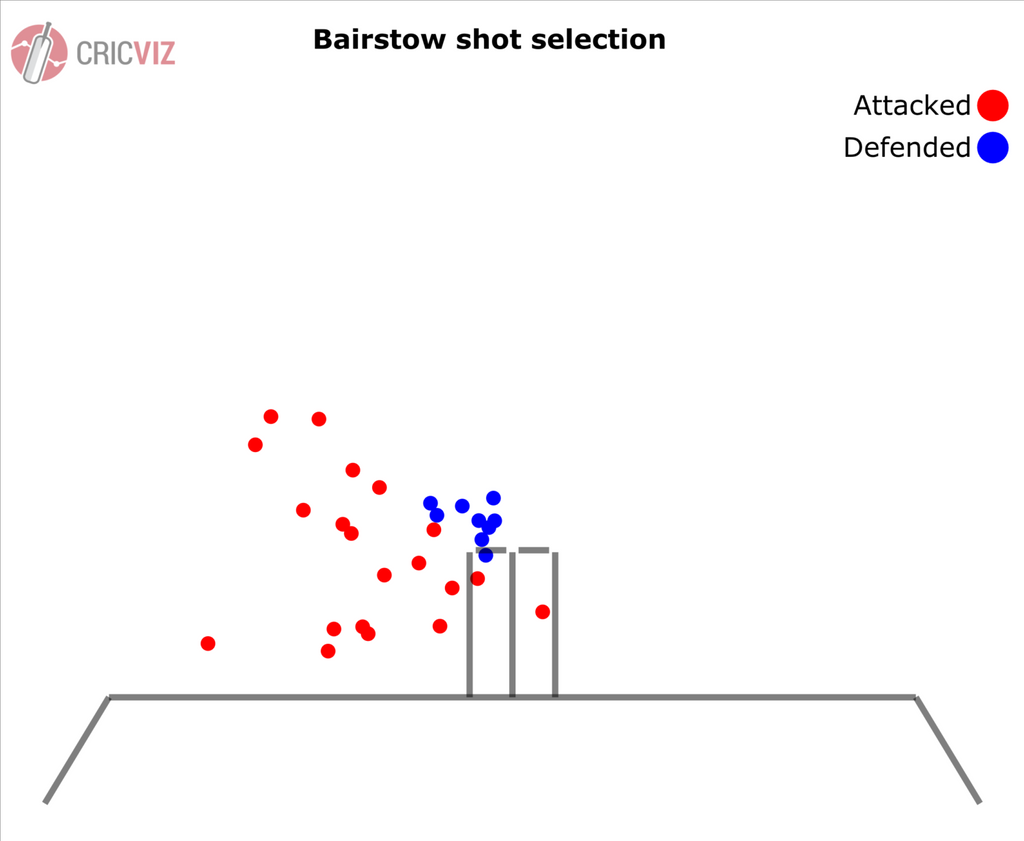

Despite the obvious aggression from Bairstow, he was far from reckless and played each ball on its merits. He wisely chose to not attack balls that pitched on a good length, and instead waited for the balls that were either too short or too full.

Additionally, Bairstow was careful to keep out the deliveries that were in the danger area around the top of his off-stump.

Without his enterprising knock, backed up by Moeen Ali’s first half-century in ten Test innings, England could have been staring down the barrel of another sub-100 innings. As it was, they made 187 which could yet turn out to be a competitive score if conditions continue to be difficult for batting.

The pitch was still showing signs of life at the end of the day, despite West Indies’ openers making it through 21 overs unscathed. It has already provided plenty of talking points on a thrilling opening day in Antigua; you sense that plenty more will be said about this surface as the match progresses.