Patrick Noone looks at England’s mercurial all-rounder, Moeen Ali, whose batting reached a new low at Edgbaston on Day three.

Patrick Noone is an analyst at CricViz.

Moeen Ali’s batting is falling off a cliff. If it hasn’t already fallen as far as it possibly can fall, it can’t have much further to go.

Today’s innings was his fourth duck from the eight innings he’s batted in 2019, a wretched run during which he’s also lost his place in the ODI team after going 29 innings without a half century.

Today’s dismissal felt like a nadir had been reached, a depth hitherto not plumbed by even the most languid, mercurial of batsmen. Being bowled while leaving the ball is not that uncommon – there have been 202 such dismissals since 2006, when information of that nature was first recorded. That’s roughly 7% of all the bowled dismissals in that time; a small amount, but not a negligible one.

Moeen isn’t even the first to be memorably bowled without offering a shot in an Ashes Test. Think of Shane Warne to Andrew Strauss at Edgbaston, or of Simon Jones to Michael Clarke at Old Trafford. But on each of those occasions, the batsman was dismissed by a truly exceptional piece of bowling; so much so that the latter example is remembered as much for the delivery itself as Mark Nicholas’ unguarded exclamation of ‘That. Is. Very. Good!’ as Clarke’s off-stump went cart-wheeling off behind him.

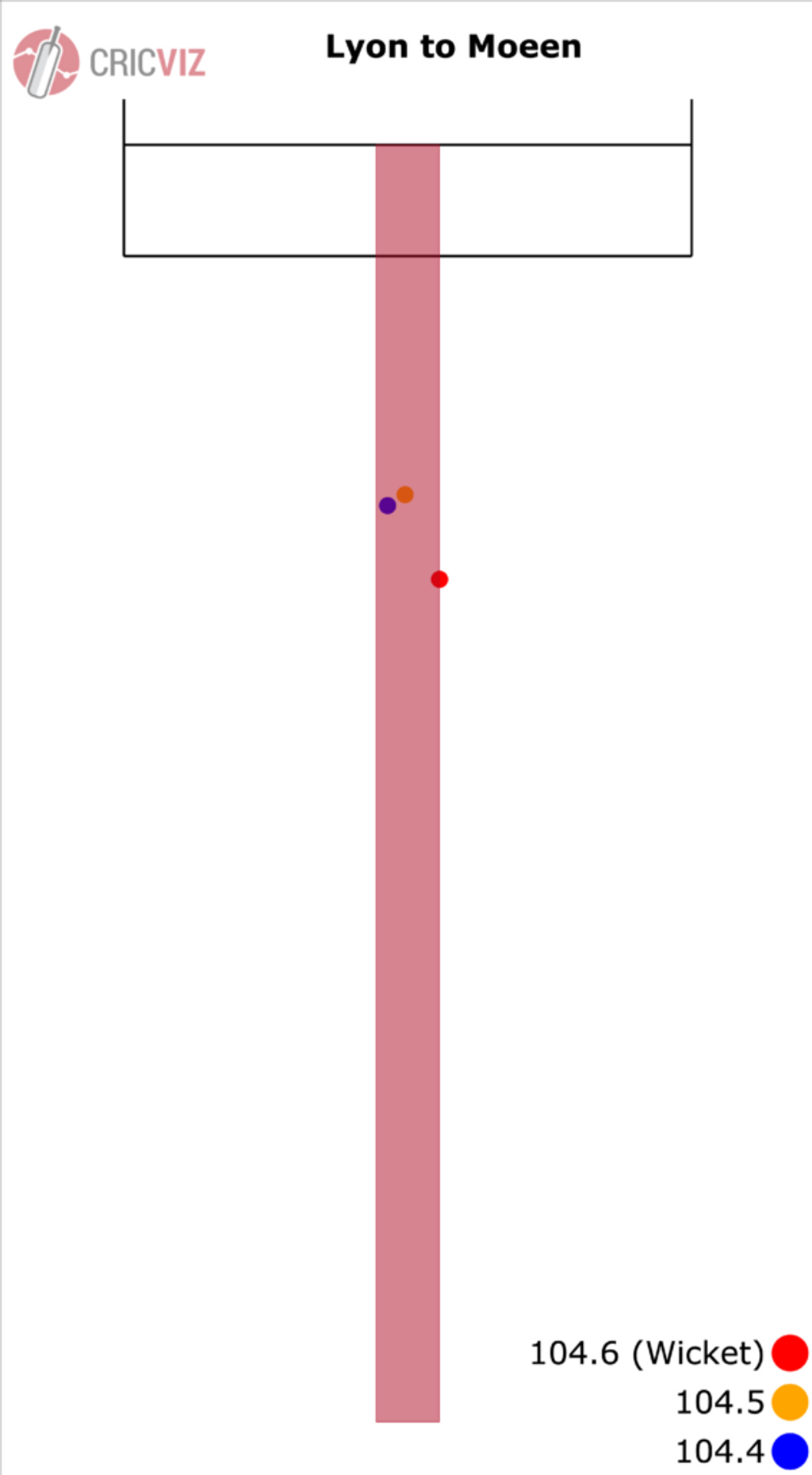

But today, Moeen wasn’t dismissed by a ball that was ‘Very. Good.’ It was a regulation ball from Nathan Lyon that pitched in line with off-stump, straightened a fraction, but not enough to not clatter into it as Moeen played for more turn than there was. Having faced the two previous balls from Lyon that were much straighter, pitching on an almost identical spot, Moeen thought the wider delivery would turn away from his stumps and wrongly thought it safe to leave.

According to our Expected Wickets model, the ball from Lyon had a 1.53% of taking a wicket, based on historical tracking data that takes into account drift, length and turn to assess the likelihood of any given ball taking a wicket. A ball with an xW figure of 1.53% chance is not a bad ball, but it neither remarkable nor exceptional.

Lyon bowled 264 balls in England’s innings, 110 of them had a higher chance of taking a wicket than the one that Moeen fatefully let go. The wicket ball was in the upper midtable of Lyon’s deliveries; a Leicester City of a ball – solid, competent and capable of causing the odd problem, but not at a level to consistently challenge the very best.

For Moeen to misjudge it so spectacularly was indicative of a batsman in the worst form of his life, of a scrambled mind unable to organise a technique that is so free-flowing and thrilling to watch when all the working parts are in order.

This is a batsman whose first Test hundred was a 281-ball vigil that took England to the brink of saving a Test. This is also a batsman who scored 102 from 57 balls in an ODI less than two years ago. He has shown that he can bat in several different ways and with great success, but there is no doubt now that this is his most prolonged period of poor form with the willow.

Moeen career has always been a peculiar tale. Called up in 2014 to replace Graeme Swann as England’s premier spinner, despite resolutely being a batsman who bowled, rather than the other way around. Since then, he has slowly metamorphosised into a bowling all-rounder; a maverick lower order batsman who might ‘come off’ rather than a frontline batsman in the team through weight of runs. While with the ball, he’s proven himself capable of bowling out even the very best players of spin, particularly in home conditions.

The oddity about Moeen’s travails with the bat are that he has rarely been so confident with ball in hand as he is now. You can tell when Moeen is at his best from the energy in his delivery stride. That extra bit of oomph allows to put more action on the ball and more revs lead to more drift. In 2017, his most successful home summer, Moeen found, on average, 2.5° of drift. It led to him taking 30 wickets in seven matches, including a hat-trick to win the Test against South Africa at The Oval.

In two Tests so far this summer, Moeen has found 2.2° of drift and he looks back to something close to his best after his Antipodean ordeals in 2017-18. Today he was admittedly expensive, but still picked up the wicket of Cameron Bancroft and bowled a reasonable line and length throughout his nine overs; no long hops, no full tosses, just dependable off-spin bowling.

After Jack Leach’s 92 as nightwatchman against Ireland, there were calls in some quarters for Moeen to be left out of the XI for this Test in favour of the Somerset man. Leach is a fine bowler who would not have let England down and, in hindsight, might have been useful in the first innings given Steve Smith’s relatively weak record against left-arm spin (he ‘only’ averages 35).

But to suggest that Moeen is not worth his place in the side on bowling alone would be wrong. He averages 29.76 against left-handers in Tests and Australia have four left-handers in their top six. Leach might be the better option to Smith, but Moeen is the better option to just about everyone else, even Bancroft, the only other right-hander in Australia’s top order.

With the game delicately poised and the tourists on the cusp of batting themselves into a good position on a fourth day pitch, Moeen’s role tomorrow will be a big one. He missed out in eye-catching style with the bat, but you wouldn’t bet against him having the last laugh with the ball.