Is self-interest, in-fighting and selection politics creating divisions in our cricket clubs? Rich Evans tackles a touchy subject in issue 11 of Wisden Cricket Monthly.

For more club cricket views and debates, subscribe to Wisden Cricket Monthly magazine.

Read more club cricket stories online.

“It needs someone to steer the ship, while dealing with all the politics, personalities and egos. Slowly but surely it eats away at you” – My club chairman

When we plot grassroots cricket’s resurgence, we theorise over formatting issues, time factors and teenage turn-off, but club disputes and divisions – chiefly the politics of selection and integration, personality clashes and one-eyed

motives – have been largely ignored.

Are there factions in your cricket club? Are your skippers weary of – or specialists in – the dark arts of selection? Do too many members place personal reward ahead of collective goals? Declining numbers are largely ascribed to the game’s innate foot-dragging when adjusting to outside forces, but what about the internal bleeding – the forces at play that we can influence?

…

Ego-management and arbitration is a large part of the cricket chairman’s role. “There’s a lot of strong personalities who tend to end up in committee positions,” my club’s leader says. “The challenge is to ensure you put the club first and set the right strategy for the club. It’s very easy to do the wrong thing because of pressure from strong personalities.

“Committee members hold a lot of sway – they’re very important. They build up their power, get more invested and make themselves indispensable, so a chairman’s job is to keep them sweet while adhering to the club development plan. If not, they may leave and jeopardise the future of the club. But some people allow self-interest to creep in and can be a bit one-eyed.”

How many true clubmen and women – club, not team – does your club have? “I often battle with people who are highly focused on one team, such as the first XI,” our chairman continues. “But I must look at the bigger picture. Most problems and bust-ups arise through self-interest. It’s very difficult to get a united group. There’s a constant distraction of having to deal with politics. You become a mediator and man-manager, smoothing arguments over because it’s best for the club, rather than joining the arguments to make yourself feel better.”

The junior section can be a hotbed for blinkered motives. “Parents can be the best allies for a club, and also the worst,” says Kristian Martin, first-team captain of Ealing CC. “We’ve had many situations when colts have been brought up to play in the fours and their parents say: ‘Why aren’t they playing in the twos’. They haven’t got a clue about the standard of senior cricket. If their parents are always telling them they should be playing elsewhere or questioning why they aren’t getting a game, it can corrupt kids. As a captain, you always try to do what’s best for the

team and club.”

But as Simon Prodger, managing director of the National Cricket Conference (NCC), affirms, it’s within the club’s best interests to settle such disputes. “There is easily a disconnection in club cricket between the junior and senior sections and clubs have to work hard at crossing that bridge,” he says. “Trying to get those parents to become non-playing members or become a part of club life, is an important part of this whole process.”

Prodger, who is also chairman of Watford Town CC, understands the challenges involved in instilling a collective spirit among players from diverse backgrounds. One of the game’s more life-affirming qualities is its ability to unite different races, cultures, ages and belief systems, but there are inevitably times when this amalgamation becomes challenging.

“Our club reflects the immediate environment,” says Prodger. “We have a large Asian membership. We have some white membership. We have no African-Caribbean membership, but we did in the past. There are different perspectives and attitudes that people bring into a club. There is a cultural adjustment within our club and it’s very

easy for divisions to appear.

“The first XI had become a separate entity. We are divided by race. A lot of the old-school members are white working class. A lot of the best players and recent arrivals are Muslim. The first XI is almost entirely Asian and Muslim. They don’t drink or socialise after the game – I’m certainly not saying that’s right or wrong, it’s just a fact. That causes disaffection with some of the non- playing, older membership, who can’t get to know who’s representing the club.”

Clubs have a responsibility to try to unite players from a variety of cultures and backgrounds

Clubs have a responsibility to try to unite players from a variety of cultures and backgrounds

Martin also recognises the difficulties for young, part-time players to feel part of a club’s fabric. “Lots of our colts are private school lads so we don’t see them until half-way through the season,” he says. “How can they feel a big part of your squad when they’re only there for half a season? We’ve got 350 juniors and five men’s teams on a Saturday. There’s so many members that people can be lost among that big pool of players.”

…

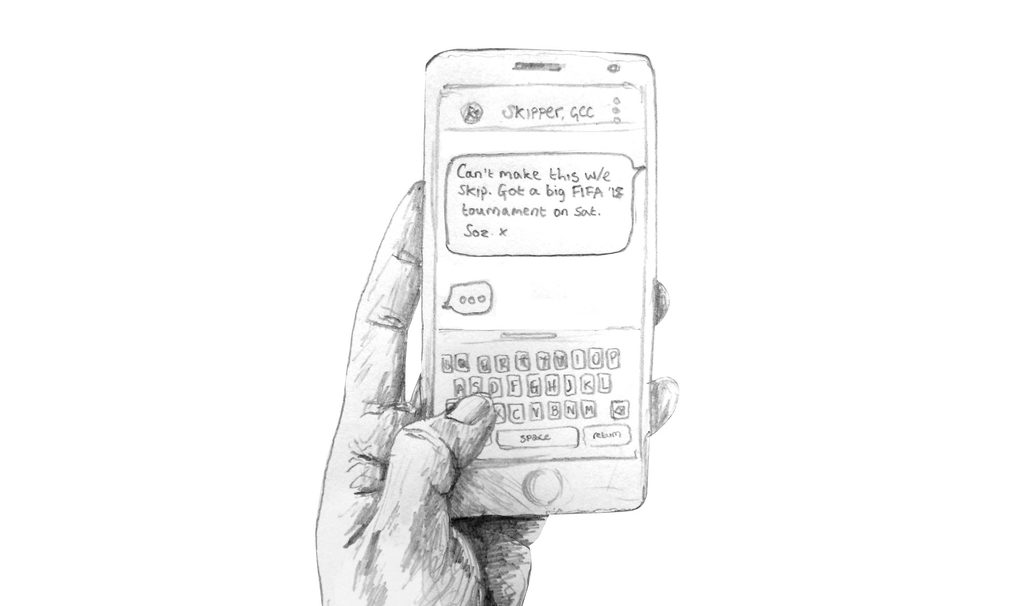

The weekly selection process can be a dirty game. Fellow skippers will know the excuses: “I want to play with my mates” … “I get more of a game in the threes” (big fish, small pond syndrome) … “If I’m not in the first team, I’m unavailable”. Sometimes a player just doesn’t fit the ethos of a given XI: “It’s too serious – I just want to play ‘picnic cricket’”.

Some players have an inflated view of their skillset and are deeply driven by personal enactment. Millennials are time-poor and the yearning for instant, projected success has heightened, but while players are often keen to endorse their self-worth on the pitch, many can’t apprehend that their real value lies off it. The dedicated work of the few that keep our clubs sustainable can be a thankless duty.

“In cricket and life, people are a bit more selfish,” says Martin. “They want to turn up and earn their match fee. They want to bat and bowl, but you can’t keep everyone happy. Going back 10 or 15 years, players were very happy just to win, but society is changing. It’s now: ‘I had my bat and bowl. We didn’t win but at least I got my money’s worth’.”

While selection can be a tough job for the skipper, especially those at the bottom of the food chain, they aren’t all angels. They can collude behind the scenes to manufacture their best line-up to the detriment of a higher XI. Scan the teamsheets for your upcoming fixtures: Are your line-ups a fair reflection of the most talented/in-form balanced XI in descending order? Skippers often have a diamond up their sleeve that they conceal from the lordlier skipper above.

A club needs fluidity in team selection, but too much rotation makes it difficult for a player to become emotionally attached to an XI, and the very thing a club should promote – a sense of belonging – can be broken. Managing individual requests, egos and team objectives, while being mindful of the greater good, is a balancing act where equilibrium is almost impossible.

Selection can be a weekly cluster headache for a club cricket captain

Selection can be a weekly cluster headache for a club cricket captain

Utopia would be every player making themselves available for the club – not a team – but the modern club cricketer is a fragile, flaky soul. While clubs must attempt to cater to their members’ desires and players occupying a peripheral role (the ‘fill-in’) must be handled carefully, flat-out refusals to step up or down in a club’s time of need

can create factions.

Phil Mist, chairman of Bicester & North Oxford CC empathises: “There’s been lots of occasions in the last eight years where people have been dropped from the first XI and replaced by someone new to the club or coming up from the second team, and that person has just walked away. There has been a general attitude from a lot of first XI players of ‘I won’t play for the twos’, which is part of the merry-go-round.”

My club chairman weighs in: “It’s not true of our first XI, but in many clubs the first XI comprise the members who do the least and care the least for the club,” he said. “Particularly when you’re desperately trying to win promotion, you may recruit the types of players who aren’t going to be long-term members. The club’s not part of their DNA. They have no loyalty.”

Prodger adds: “You experience players arriving and departing en bloc, who go from club to club. One day they might run out, but there are enough clubs around us for that migrant movement to continue.”

…

The game is played and administrated by some wonderful people – it’s the people that keep us turning up, right? – but if split loyalties continue to divide clubs, if the migration movement persists, if the family disconnect continues, if the club constitution and selection policy remains a neglected pin-up on the pavilion noticeboard, and if poor attitudes continue to cause conflict – on and off the pitch, both within and between clubs – then where will that leave us?

It’s about modifying mindsets, but it’s not easy. As CLR James once wrote: “A particular generation of cricketers thinks in a certain way and only a change in society, not legislation, will change the prevailing style”. We can’t control societal factors and the gradual shrinking of the wider cricketing landscape, but we can inspire positive change at our own club, even if it’s just being more sympathetic to the broader perspective. In the current climate, grassroots cricket must have its soldiers pulling in the same direction. It can’t afford a civil war.

READ THE PREVIOUS CLUB DEBATE:

https://www.wisden.com/stories/your-game/club-cricket/club-debate-friendly-fire-need-rescue-friendly-cricket-obscurity

https://www.wisden.com/stories/your-game/club-cricket/club-debate-letters-readers-friendly-cricket-needs-rescuing