Will the game’s new laws enhance or hinder club cricket? Rich Evans dissects the most important changes you need to know ahead of the new season

In October last year, the MCC, the custodians of the Laws of Cricket since the club’s formation in 1787, issued a new code for the first time since 2000 following a global consultation with players, umpires and administrators at all levels. While some of the laws tried to address issues relating to safety and participation, in many ways the new code was prompted by fear: anxiety over law suits, the dispirit of cricket and the rising tide of gamesmanship.

According to the MCC’s laws sub-committee, the guiding objectives were making the laws more interpretable, more inclusive to all, and minimising the type of misconduct that has caused players and particularly umpires to leave the game.

Anything that helps boost participation is welcome, but what ramifications will the law changes have on the recreational game?

BEAMERS

At my league’s AGM in February one new law in particular prompted murmurings of discontent and was labelled ‘unfair’ in the minutes. A bowler who delivers more than one beamer, which passes above waist height of the batsman, irrespective of speed, must now be taken out of the attack.

Previously, slow balls – a rather ambiguous term – could be delivered up to shoulder height. Meanwhile, repeatedly bowling above head-height bouncers could also trigger a warning, while deliberately – how can an umpire tell? – bowling front foot no balls could lead to immediate suspension.

Kristian Martin, first XI captain at Ealing CC, is not concerned by the new beamer law’s implementation in his league but worries for those further down the food chain. “It’s a fine line between trying to work in the interests of health and safety and discouraging people from bowling. It will affect junior cricket – the ECB are pretty wishy-washy on their guidelines.”

Darren Sammy reacts after ducking a beamer

Darren Sammy reacts after ducking a beamer

The ECB’s tutorial recommends “that a bowler under 13 is to be no balled for every high toss but that the player should not receive a warning or be removed from the attack unless the umpire deems the delivery as dangerous or deliberate”.

Peter Hindstridge, the umpire co-ordinator for the Hertfordshire Cricket League and chairman of the Hertfordshire Association of Cricket Officials Committee, believes the rule change has over-evolved. “When you have two separate definitions you inevitably invite questions and judgement calls on ‘was that a slow ball’, so at least if everything is waist height you remove that level of dispute. My reservation is the double-change. Moving everything to waist height on it’s own is OK. And moving everything from a two-stage process to a three-stage process is OK. But when you overlay both together it seems harsh.”

Both Martin and Hindstridge have concerns about how the new law will affect the development and morale of young bowlers, especially spinners. “The ECB have been rushing to catch up but, to be fair, it’s not that straightforward,” adds Hindstridge. “I said last autumn we really needed clarity on this early. Leagues need time to construct match regulations and league handbooks, and if you do it too near to the season how do you communicate this to players and umpires?”

The ECB have, however, published some useful resources for recreational cricketers and officials. A video tutorial points out that “the law doesn’t say the ball must be directed at the striker, so every ball above waist height, even if its wide of a batsman, is a no ball and must be treated as dangerous”. Persistent bouncers above head height could even lead to suspension.

RUN OUTS

The law relating to the non-striker leaving their ground early has also been amended. Having already been introduced in international cricket, the MCC has extended the point at which the run out of the non-striker can be attempted to the moment at which the bowler would be expected to release the ball. As outlined by MCC’s laws sub-committee: “If you do not want to risk being run out, stay within your ground until the bowler has released.” Batsmen, you’ve been warned.

Sri Lanka’s Sachithra Senanayaka ran out England’s non-striker Jos Buttler in 2014

Sri Lanka’s Sachithra Senanayaka ran out England’s non-striker Jos Buttler in 2014

“If you go back pre-2000, bowlers could run-up, complete their delivery action without letting go of the ball, swing their arm back round, take the bails off and appeal,” says Hindstridge. “The balance was completely in favour of the bowler. In 2000, they changed the law to say once the bowler entered his delivery stride they are not permitted to attempt a run out. That resulted in batsmen trying to leave their crease too early because the balance had shifted. We’ve now got a law pitched between the two extremes. It will make a difference.”

Martin, however, isn’t convinced. “I’d rather it as it was with a warning,” says Ealing’s first-team skipper. “Is it a law change that is desperately required? No one is halfway down the wicket before people are bowling. It’s been changed for the sake of it.”

Another tweak to the run-out rule sees an end to the ‘bouncing bat’ scenario: if a batsman dives to make their ground and the bat bounces up off the turf, then they’re protected from being run out as long as they’ve gained their ground and “continued forward momentum”.

TIME PENALTIES

If a player is absent while fielding, unless in exceptional circumstances or if the absence was caused by an “external blow”, that player will incur penalty time equivalent to the total time spent off the field – the time they will have to spend on the field before being able to bowl or, if the innings had terminated, bat. The rolling over of the batting innings is new. Unlike the 2000 code, which allowed you to leave the field for 15 minutes without penalty, there is no grace time, so no Friday night vindaloos.

BAT SIZE

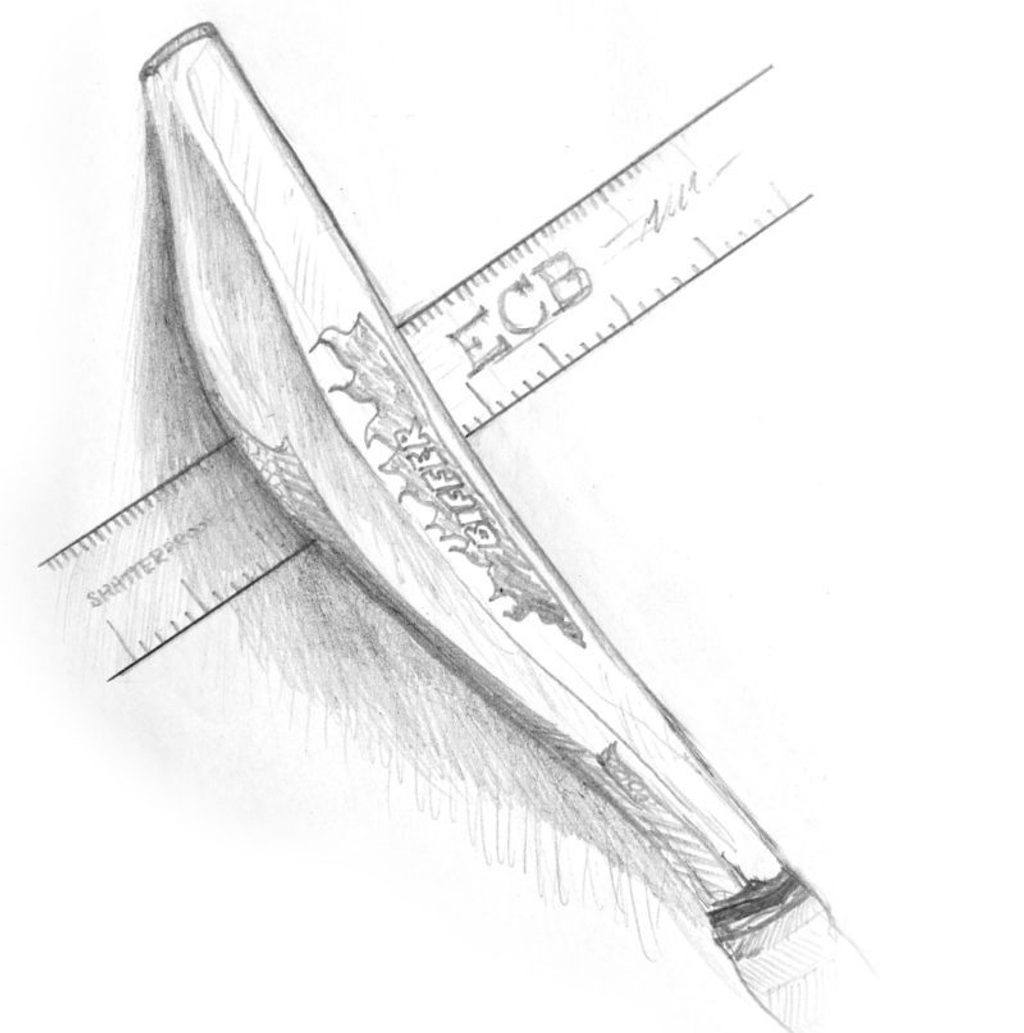

Meanwhile, the MCC have outlined a size limit for the edge of a cricket bat (max 40mm) and its overall depth (max 67mm). Introduced in the professional game in an attempt to strike a better balance between bat and ball, at recreational level is is largely about protecting fielders, officials and spectators from the dangers of monster bats. However, the ECB recently outlined a phased approach to this law change at grassroots level, presumably to lessen the blow to those who’ve recently invested in a non-compliant blade.

2018: No change to bat sizes

2019: New bat sizes introduced to minor counties and top two tiers of ECB Premier Leagues

2020: New bat sizes introduced into all recreational cricket

ON-FIELD BEHAVIOUR

Umpires are now empowered to warn players for unfair conduct and, on subsequent instances, issue five penalty runs or suspensions under law 42. In a bid to address the “deteriorating levels of behaviour” officials now have the power to deal directly and instantly with ill-discipline, not too dissimilar to football’s yellow and red card system. There are four levels of sanction:

Level 1: Warning then five penalty runs to the opposition for a repeat offence (includes dissent, obscene gestures, poor language, aggressive appealing)

Level 2: Five penalty runs to the opposition (includes serious dissent, physical contact)

Level 3: Offending player is suspended for a number of overs, depending on the length of the match, plus five penalty runs (includes intimidating an umpire by language or gesture and threatening to assault a player)

Level 4: Offending player is removed from the field for the rest of the match, plus five penalty runs (includes threatening to assault an umpire, deliberate physical contact with an umpire, physical assault and other acts of violence)

Shane Warne (R) confronts Marlon Samuels during a Big Bash League match

Shane Warne (R) confronts Marlon Samuels during a Big Bash League match

Martin believes it will “improve the game and behaviour” and work effectively at the elite level of the recreational game, but that a “very difficult situation” awaits in matches that aren’t officiated by neutral umpires. The Herts league will only exercise law 42 from the top division down to division 6B, where the requirement for a ‘qualified’ umpire ends. Hindstridge says some umpires are apprehensive about being “judge, jury and executioner” and that their job is to manage the game before sanctions are required.

HEALTH AND SAFETY

Another potentially controversial introduction outlines that play will be suspended if one umpire deems conditions dangerous or unreasonable, whereas previously it had to be a joint decision. It’s easy to foresee problems occurring below the levels officiated by panel umpires.

“That’s a bad rule change,” says Martin. “It seems very much ‘health and safety: let’s cover ourselves’. If you get an umpire who doesn’t want to stand in the rain you could have games needlessly called off.”

When Hindstridge provides the context, however, you can understand the motivation behind the law, even if you don’t agree with it. “About two years ago there was a court case in the Birmingham area,” he said. “A player made a sliding stop and injured himself and sued the umpires because he considered the conditions unsuitable for play. The judge ruled that it was largely the player’s fault and that the umpires had kept meticulous notes of the conditions to demonstrate that they hadn’t been negligent.” If a player got injured and sought legal action after one umpire had rated conditions playable and the other had deemed them dangerous, the official who kept the teams on could be put in a vulnerable situation.

It’s going to be an interesting opening few weeks of the season as players acquaint themselves with the new law changes

It’s going to be an interesting opening few weeks of the season as players acquaint themselves with the new law changes

***

While the ECB and local associations have the flexibility to amend and influence certain rules changes, the laws of cricket adopt largely a one-size-fits-all approach. But is that workable?

Some laws – such as bowlers being penalised only for a no ball and not any subsequent byes scored off the delivery – seem very logical. Others, such as the beamer ruling, feel too open to interpretation and potentially damaging to the confidence of young cricketers. Safety and participation were at the core of the lawmaker’s objectives, but in this instance health and safety appears to be directly competing against participation and inclusion. If a young spinner bowls a couple of slow beamers and is then removed from the attack, how will that keep them in the game?

Increased likelihood of suspensions – of players and of play itself – also do little to support the ECB’s ‘Get The Game On’ campaign. Empowering umpires to penalise, suspend and dismiss players is a brave call. Much will depend on the capability, personality and partiality of the individual. Keep a close eye on how this power is executed below panel umpire-level in which teams have a regular official with a strong allegiance to the club. If these powers are not executed tastefully, the law introduced to tackle poor behaviour could in fact inflame it.

Useful resources:

ECB: https://www.ecb.co.uk/be-involved/officials/resources

MCC: https://www.lords.org/mcc/laws-of-cricket

Last month’s debate:

https://www.wisden.com/stories/your-game/club-cricket/the-club-debate-where-have-all-the-families-gone

https://www.wisden.com/stories/your-game/club-cricket/club-debate-letters-where-have-all-the-families-gone-readers-views