Gideon Haigh relives the night that changed the game forever, as a near-capacity crowd turned out for a floodlit match at the SCG between the WSC Australia and West Indies sides.

Bill Macartney [World Series Cricket’s publicity director] leaned back in parodied self-satisfaction as his companions looked down on the sea of faces beneath the SCG’s executive chamber. “So,” he drawled, “what do you think of my crowd?” It was 8pm on Tuesday November 28, 1978, and WSC had 50,000 rocking, rollicking converts.

“After all the hype and the publicity,” said ticket manager Bruce McDonald, “I would have been disappointed with anything less.”

Their frivolity actually caused some offence in the party. “I really had anticipated a big crowd,” McDonald recalls, “so I was quite underwhelmed. But it upset a few people when they thought I was pooh-bagging the whole thing.” For many in attendance, WSC had become more than cricket, more than business, an end in itself.

McDonald had called Packer before gates opened to describe lines of spectators twisting down Anzac Parade. The 2.15pm toss was transacted for Ian Chappell and Clive Lloyd by 15-year-old Glen Michelic, a WSC coaching find from Fairfield, and the Australians fanned in the field to the strains of “C’mon, Aussie” hurling giveaway white balls into the 5,000 early arrivals.

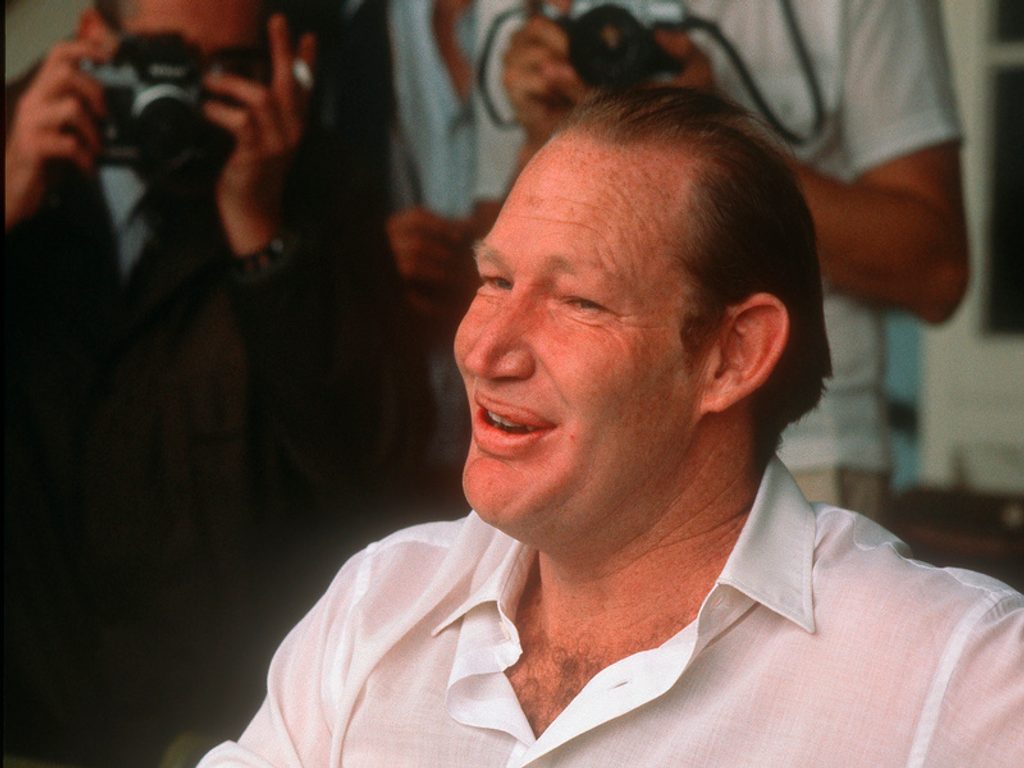

Kerry Packer during a match between English journalists and Australian journalists

Kerry Packer during a match between English journalists and Australian journalists

Curious and deferential WSC officers, like an occupying army visiting the deserted bunker of a routed enemy, studied the memorabilia lining their executive room two floors up in the SCG members’ stand. Attentive to the play, they toasted Lillee’s third-ball victory over Viv Richards. But, as Australian success filled the afternoon, and the Hill’s voice swelled, their celebrations became less of cause than effect.

Packer arrived in mid-afternoon, joining McDonald at the turnstiles in the fashion of a retail chain owner keeping his common touch at the till. Reality dawned at tea when an updated crowd figure of 30,000 was confirmed in expectation of the Australian innings. A glance out the back of the executive room confirmed more to come. WSC was not against the establishment this evening. It was the establishment.

Packer had already taken the venturesome step of admitting ladies to the members’ for the first time and, when worried police asked that the gates be opened to ease queues still banked up at turnstiles that had clicked 44,377 times, approval was readily given.

John Cornell, who rarely permitted himself more than a sly smile, was beside Paul Hogan, Austin Robertson, Delvene Delaney and himself. “These people have found truth,” he muttered mystically. He rushed the attendance figure to the press box personally, and dashed to fetch Lillee when the Australian innings began.

Colin Croft bowling in the first match of World Series Cricket

Colin Croft bowling in the first match of World Series Cricket

JP Sport’s first client, 4-12 in the bag, had never visited the executive room before and admired the view with awe. “There were hordes of people and cars as far as the eye could see,” he wrote. “As I looked out in the gloomy light I got a tingling feeling through my body.” Tony Greig, arriving late after a cross-country flight with the Amisses and Woolmers, choked back tears.

Chasing 128, the Australian batsmen never had to touch the heights. Ian Davis, striking Bernard Julien for three smart fours, joined his captain in an even-time stand of 42. When the target narrowed to 34 runs with 20 overs remaining, three cheap wickets stirred the Hill’s “C’mon, Aussie” choir, but robust blows from Davis and Marsh clinched the match by 9.20pm.

Match reports were revealing, not so much in what was written but what was not. The local press contingent was three-strong: the Australian’s Phil Wilkins had only two news agency companions. Packer’s Fairfax rivals gave their syndicated copy grudging space, although the organisation’s National Times a fortnight later carried Adrian McGregor’s colourful, intelligent tribute. “The incongruity of it all,” he wrote. “That Packer at that moment, so absolutely removed from the hoi polloi, should have… achieved the proletarianisation of cricket. He had enticed sports fans out of the pubs… transforming the subtleties of traditional cricket into the spectacular that is night cricket.”

“The incongruity of it all,” Adrian McGregor wrote. “That Packer at that moment, so absolutely removed from the hoi polloi, should have.. achieved the proletarianisation of cricket.”

At his moment of triumph, Packer was also reflective, and intently entertained a cross-section of his world: the day-time television favourite Mike Walsh, celebrity sportscaster Mike Gibson, the telethinker Bruce Gyngell and agent Harry M Miller mixed with Lillee and Marsh, Sobers and Lloyd.

Greig found his boss thoughtfully absorbed when he whispered his belief: “This is it.”

Originally published in 1993, an updated version of The Cricket War, with new photographs and a new introduction by the author, is out now, published by Bloomsbury